In Part II of Towleroad's summary and analysis of the Prop 8 oral argument, we pick up with Ted Olson's argument against Prop 8. Read Part One HERE.

And listen to audio and read the full transcript HERE.

Here's what we have discussed so far:

Here's what we have discussed so far:

-

The justices are definitely interested in the standing question. The Chief Justice, though playing a gate-keeper role to make sure standing gets addressed, expressed skepticism. The key will be to see if he is playing the devil's advocate or expresses skepticism with Mr. Olson, too. But, in addition to the Chief Justice, Justice Ginsburg is highly skeptical. If we see more evidence of this below, look for lack of standing to be the odds-on favorite of many pundits. But, remember, there were lots of other questions on the merits from all the justices. That does not mean that they are going to pass by standing. Nor does it preclude a 9-0 opinion saying the Proponents had no standing.

-

Mr. Cooper was forced to admit that the only injury caused by allowing gays to marry would be redefining marriage, which is clearly not an injury whatsoever. He also admitted that gays simply do not advance the government's interest in encouraging natural procreation within wedlock (even though he's wrong about that), which proves that a ban on gays marrying cannot actually advance that interest, either. If it weren't for some help from Justice Scalia, this case would be over on this point alone.

-

Justice Kennedy showed that he, like many, are struggling with this issue. The addition of this relatively emotional admission (emotional, at least, by Supreme Court argument standards) is telling of his honesty and the reality that many people are going through right now. This may suggest that Justice Kennedy is going through his process, perhaps with a little help from everyone else along the way.

We pick up with Ted Olson's argument and see what lessons we can draw,

AFTER THE JUMP…

Ted Olson, the lead attorney challenging Prop 8,fared better.

Mr. Olson got a bit further into his openingremarks before being interrupted by Chief Justice Roberts about standing. So,here, we already see that a given question or a tendency to interrupt does notforeshadow anything. However, I will say that both times the Chief Justiceasked a standing question, it was tilted toward showing skepticism: to Mr.Cooper, he asked how Proponents are any different than random citizens, whonever have standing; to Mr. Olson, he asked how Proponents could ever havestanding when the State of California declined to appeal at all. Neitherattorney said anything new or that wasn't in the briefs. I would color theChief Justice skeptical on standing. But, don't color the entire Court inthe same shade. Justice Kennedy jumped in first with a few questions critical of Mr. Olson's no-standing view and repeated the argument from theCalifornia Supreme Court: without the right to defend the initiative, the rightto "propose and enact" an intiative or referendum is meaningless. Justice Alito was there with him with a follow up. Justice Sotomayor was also worried about what happens when state officials simply don't like a law and stop defending it; "how do you get the law defended in that situation?" Mr. Olson had no answer, but returned to his talking points on direct injury.

Mr. Olson got a bit further into his openingremarks before being interrupted by Chief Justice Roberts about standing. So,here, we already see that a given question or a tendency to interrupt does notforeshadow anything. However, I will say that both times the Chief Justiceasked a standing question, it was tilted toward showing skepticism: to Mr.Cooper, he asked how Proponents are any different than random citizens, whonever have standing; to Mr. Olson, he asked how Proponents could ever havestanding when the State of California declined to appeal at all. Neitherattorney said anything new or that wasn't in the briefs. I would color theChief Justice skeptical on standing. But, don't color the entire Court inthe same shade. Justice Kennedy jumped in first with a few questions critical of Mr. Olson's no-standing view and repeated the argument from theCalifornia Supreme Court: without the right to defend the initiative, the rightto "propose and enact" an intiative or referendum is meaningless. Justice Alito was there with him with a follow up. Justice Sotomayor was also worried about what happens when state officials simply don't like a law and stop defending it; "how do you get the law defended in that situation?" Mr. Olson had no answer, but returned to his talking points on direct injury.

Justice Sotomayor's questioning is a perfect example of why we cannot read too much into the tea leaves of oral argument. She asked pointed, sharp standing questions to each attorney: demanding a clear statement of injury from Mr. Cooper (which he could not provide) and a clear answer on state nullification from Mr. Olson (which he couldn't provide, either).

When he moved to the merits, Mr. Olson's next move was abreath of fresh air. He turned to the broadest argument we can make for anational right to marry: that any ban on gays marrying violates due process.While this shouldn't surprise us — this argument was not only front-and-centerin his brief, but also invited by the Court when it crafted its broad QuestionsPresented — it reminded me of the great potential of this case and Mr. Olson'sconfidence in his position.

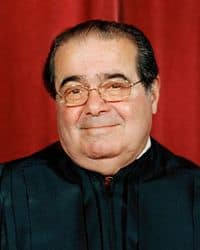

As expected, the argument drew forcefulresponses: a nuanced one from the Chief Justice and an angry, bitter one fromJustice Scalia. The Chief Justice made the point that bans on gays marryingneed not only be seen as antigay discrimination. It is undisputed that marriageas an institution developed without gays; keeping it that way is notnecessarily discrimination. Aside from ignoring pre-Christian "unions" in Greece and Rome and focusing only on the development of marriage in a Judeo-Christian tradition, what the Chief Justice misses with that argument is the discriminatory and silencing role of the closet. Countless institutions developed without gay people because gays were shoved underground and forced to hide in order to survive. Plus, that a practice has always existed does not mean it isn't discriminatory.

Justice Scalia glommed on to that interesting — butultimately unsatisfying argument — by demanding, in a tone typical of thearchconservative justice, that Mr. Olson tell him "exactly when" itbecame unconstitutional to ban gays from marrying. After all, there was no gaymarriage right in 1791 (the year we ratified the Bill of Rights).

Justice Scalia glommed on to that interesting — butultimately unsatisfying argument — by demanding, in a tone typical of thearchconservative justice, that Mr. Olson tell him "exactly when" itbecame unconstitutional to ban gays from marrying. After all, there was no gaymarriage right in 1791 (the year we ratified the Bill of Rights).

Mr. Olson showed his confidence, experience, andhis standing at the Court by doing something I tell my students and youngattorneys never to do: answer a question with a question. His argument wasamazing: If that's your concern, when did it become unconstitutional to baninterracial marriage? Justice Scalia got testy, demanding an answer. Mr. Olsonsaid he couldn't point to a date, but that wasn't the point: No court requiresthat kind of precision. Mr. Olson could have gone further and argued that this kind of discrimination is always anathematic to American principles of liberty and equality; that it took a while for us to realize it is our fault, not a gay person's burden to bear.

What was happening here was Justice Scalia hypinghis view that the Constitution is "dead, dead, dead," and was eggingMr. Olson to say that the Constitution should change as times and social moreschange. Strategically, Mr. Olson declined to take the bait. Justice Scalia bloviated, "How am I supposed to decide a case then, if you can't give a date when the Constitution changes?"

It was almost as if Mr. Olson was not going to bother with such nonsense. He responded by noting that when the Court decided that separate-but-equal schools were unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education, for example, no one ever required something as ridiculous as a date the Constitution changed. And that's because the Constitution isn't changing. Just because society's conceptions of freedom and equality a century ago were not our conceptions of freedom and equality does not mean that the Constitution has to stand for the versions of freedom and equality that prevailed when we had slaves. But, there will be no persuading Justice Scalia on this point. In fact, he even admitted that he was demanding something unprecedented: "I know," he said, "I know." The Court has never required anything of the sort. "That's exactly the problem." It's clear that Justice Scalia wants to upend centuries of rights jurisprudence. There's very little rational argument can do about that now.

The Chief Justice and Justice Kennedy then asked questions about the "odd rationale" (Kennedy's words) the NinthCircuit gave for rejecting Prop 8 — namely, that by taking away a rightalready given, Prop 8 violated the principle of Romer v. Evans. To theChief Justice, Mr. Olson reiterated his fundamental rights argument, butconceded that there were several, narrower ways the Court could decide thecase. To Justice Kennedy, Mr. Olson declined to be overtly critical of a lowercourt opinion that came out on his side, but you could tell that Mr. Olson waspositioning himself at the boundary and allowing the Court a lot of leeway to strike down Prop 8 without, as Justice Kennedy noted, going into uncharted waters and finding a cliff at the end of the line.

It was Justice Sotomayor who brought up theslippery slope argument about polygamy: If marriage is a fundamental right, Mr.Olson, can we ever have legitimate restrictions on it? Yes, he said. Prop 8 ispart marriage restriction, part status discrimination; it targets gays as aclass. A restriction on polygamy would target conduct, not a class of personstraditionally discriminated against.

It was Justice Sotomayor who brought up theslippery slope argument about polygamy: If marriage is a fundamental right, Mr.Olson, can we ever have legitimate restrictions on it? Yes, he said. Prop 8 ispart marriage restriction, part status discrimination; it targets gays as aclass. A restriction on polygamy would target conduct, not a class of personstraditionally discriminated against.

The take away from this is that having chosen to make the broadest argument about any ban on the freedom to marry violating due process, Mr. Olson had to spend more than half of his time at oral argument swatting down skeptical questions from both wings of the Court about the very breadth of his proposal. But, don't dismay. Posing the broad argument was likely a strategic decision that allows a more moderate approach to seem like a reasonable compromise.

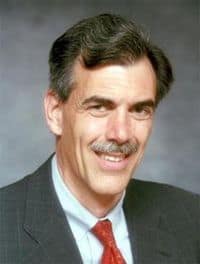

Don Verrilli, President Obama's SolicitorGeneral, makes the President's "8 State Solution" Argument.

When a state like California grants gays theright to do everything, including  adopt children or have a family through asurrogate, then Mr. Cooper's argument that the state's interest in heterosexualcouples' procreative ability has no "legs." Several justices notedthe irony of the '8 State Solution' — it says that the most pro-gay states areviolating the rights of gays, but it leaves out the states that don't allow gaysany rights. Mr. Verrilli answered that question by agreeing with my argumentthat the 8 State Solution was inherently illogical as a matter of law: It's notjust the pro-gay states; the anti-gay states will also have trouble justifyingtheir bans on gays using the word "marriage." This case, however, isabout a unique state.

adopt children or have a family through asurrogate, then Mr. Cooper's argument that the state's interest in heterosexualcouples' procreative ability has no "legs." Several justices notedthe irony of the '8 State Solution' — it says that the most pro-gay states areviolating the rights of gays, but it leaves out the states that don't allow gaysany rights. Mr. Verrilli answered that question by agreeing with my argumentthat the 8 State Solution was inherently illogical as a matter of law: It's notjust the pro-gay states; the anti-gay states will also have trouble justifyingtheir bans on gays using the word "marriage." This case, however, isabout a unique state.

Mr. Verrilli was the one who had to deal with theChief Justice's and Justice Alito's suggestions that this was all moving toofast. Gay marriage is new, Justice Alito said, preventing us from actuallyseeing its effects. The Chief Justice's voice actually grew louder on the audiowhen he challenged the demand for a nationwide right to marry without lettingthe public debate continue to work it out.

To use a baseball analogy, it seems like Mr. Olson and Mr. Verrilli were playing different roles on a team. If it's the bottom of the ninth inning and you have a man on second and need one run to tie and two runs to win, Mr. Olson was trying to hit a "walk off" home run so the game would be over and everyone could go home. Mr. Verrilli was aiming to just get the runner home, setting up extra innings where some of his heavy-hitting teammates could end the game in a little while. Although Mr. Verrilli faced some questions about a broad holding, he was hitting back the justices' skepticism with viable alternative options.

Mr. Cooper gets another shot (a rebuttal), butJustice Ginsburg has his number.

In an extra-long 10 minute rebuttal (extendedbecause the justices kept Mr. Olson up there a bit too long), Mr. Cooper triedto capitalize on several justices' concerns about a nation-wide right to marryby arguing that an anti-Prop 8 decision could never be narrowed to justCalifornia. Justice Ginsburg snapped back in only the way she can, with alesson about how Loving v. Virginia ultimately came about afterseveral, more limited decisions that paved the way for a national right. Mr.Cooper's only response was the procreative argument about which severalconservative justices had already expressed skepticism: that the government hasno interest in banning interracial marriage, but it does have an interest in banninggays from marriage because gay people cannot advance the govermental interestin encouraging responsible procreation. I think the 40,000 children of gayparents in California would disagree.

In an extra-long 10 minute rebuttal (extendedbecause the justices kept Mr. Olson up there a bit too long), Mr. Cooper triedto capitalize on several justices' concerns about a nation-wide right to marryby arguing that an anti-Prop 8 decision could never be narrowed to justCalifornia. Justice Ginsburg snapped back in only the way she can, with alesson about how Loving v. Virginia ultimately came about afterseveral, more limited decisions that paved the way for a national right. Mr.Cooper's only response was the procreative argument about which severalconservative justices had already expressed skepticism: that the government hasno interest in banning interracial marriage, but it does have an interest in banninggays from marriage because gay people cannot advance the govermental interestin encouraging responsible procreation. I think the 40,000 children of gayparents in California would disagree.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about thishearing came at the end, where Mr. Cooper was the one who almost conceded thatthe freedom to marry is coming, sooner or later. His plea, his only plea, wasfor the Court to stay out of it. The Court need not even worry about Mssrs.Katami and Zarrillo or Ms. Stier and Ms. Perry because the freedom to marry"will be coming back to California." Ostensibly referring to publicopinion polls, Mr. Cooper has the nerve to ask the Court to continue injuringeven the plaintiffs (let alone the rest of California) because gay persons'marriages are things everyone should vote on. The justices did not have time toquestion this line of argument, but it strikes me as the height of Mr. Cooper'sand his movement's dismissive heartlessness: these people don't need theirrights guaranteed because eventually, my liberal kids are going to give themtheir rights.

Conclusions

For those willing to make predictions from oral argument alone, look at the following things we learned:

-

Several members of the Court are concerned about standing, asking questions skeptical of proponents' standing to both sides.

-

Justice Kennedy may have given us his version of "I'm evolving every day on this issue" when he said that this case is raising issues that he "has been struggling with." He is obviously keenly aware of his role as the so-called "swing" justice and does not want to tip his hat, but his words tap into the journey our entire country is taking together.

-

Mr. Cooper admitted the emptiness of his case and the lack of any real connection between Prop 8 and a state interest.

-

Some of the justices asked skeptical questions about a broad ruling, but that does not mean Prop 8 will survive. If anything, it means that Mr. Olson's strategy worked.

Hollingsworth may, therefore, end Prop 8, either on standing or the merits. Either way, everything about today's argument suggests that Mr. Cooper's conclusion is wrong. No one should have the right to vote on the legitimacy of my love. And no one has the right to hand me my rights like beneficences from a king. That is why the American Foundation for Equal Rights (AFER) and its attorneys, Ted Olson and David Boies, took us to the Supreme Court. Today, our lawyers made us proud by revealing the basic infermity of Prop 8: it singles out gays, discriminates against them, and it does so for no reason.

***

Ari Ezra Waldman teaches at Brooklyn Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. His research focuses on technology, privacy, speech, and gay rights. Ari will be writing weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues. You can follow him on Twitter at @ariezrawaldman.