The most dangerous line in the Supreme Court's recent decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby doesn't come until page 46. It reads as follows:

The principal dissent raises the possibility that discrimination in hiring, for example on the basis of race, might be cloaked as religious practice to escape legal sanction. Our decision today provides no such shield. The Government has a compelling interest in providing an equal opportunity to participate in the workforce without regard to race, and prohibitions on racial discrimination are precisely tailored to achieve that critical goal.

That doesn't sound too bad; indeed, it is probably one of the few statements in Justice Alito's opinion that many of us would endorse.

Its danger, particularly to the LGBT community, rests in what is not said.

As we have discussed at length, Hobby Lobby allowed a family-run, for-profit arts and crafts company to deny its female employees access to certain contraception simply because that contraception violates the religious beliefs of the company owners.

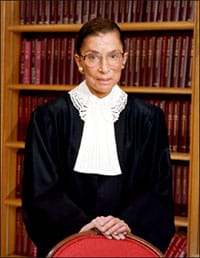

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's dissent cautioned that the Court was opening a door to allow anyone to use the pretext of religion to opt out of antidiscrimination or public accommodations laws. Justice Alito's response was to deny the charge, arguing that where the government has a compelling interest in preventing discrimination, as it does in preventing discrimination on the basis of race, the Hobby Lobby exemption would not succeed.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's dissent cautioned that the Court was opening a door to allow anyone to use the pretext of religion to opt out of antidiscrimination or public accommodations laws. Justice Alito's response was to deny the charge, arguing that where the government has a compelling interest in preventing discrimination, as it does in preventing discrimination on the basis of race, the Hobby Lobby exemption would not succeed.

But what happens when the government does not have that “compelling interest”?

Justice Alito chose a convenient example to respond to Justice Ginsburg's concern. Most people agree that discrimination on the basis of race is not just bad, but absolutely anathematic to our constitutional tradition. But no one in the Court's five-justice conservative majority has ever said that the state has a compelling interest to prevent discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Even Justice Kennedy, the author of the Supreme Court's three gay rights decisions, has carefully declined to declare that antigay discrimination merits heightened scrutiny or that the government has a compelling interest to permit gays to marry. We might believe that the same compelling interest that gives the state the power to prevent discrimination on the basis of race gives the state the same power to prevent discrimination on another status that has nothing to do with an individual's ability to contribute to society—namely, sexual orientation or gender identity. But there are many judges out there who are not yet there. Congress isn't even there yet.

CONTINUED, AFTER THE JUMP…

As lower courts begin to interpret the reach of Hobby Lobby and as the first case at the nexus of Hobby Lobby and the LGBT community comes forward, judges will look specifically to Justice Alito's language at the end of his opinion cabining the decision's reach. Judges will notice that Alito appeared to condition the inapplicability of Hobby Lobby on a “compelling interest” to prevent discrimination. A conservative judge will then review the long history of “compelling interest” jurisprudence and find controlling precedent binding him to apply it to race or national origin or religion, but find precious few precedents arguing that the Constitution permits the state to use the same strong response to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation (let alone gender identity). This could give him license to expand the Hobby Lobby religious exemption to carve a hole in law – or in an executive order – aimed at preventing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Needless to say, we not only have to stay tuned to the next developments, but remain vigilant against unjust expansion of the Hobby Lobby precedent.

***

Follow me on Twitter and on Facebook. Check out my website at www.ariewaldman.com.

Ari Ezra Waldman is a professor of law and the Director of the Institute for Information Law and Policy at New York Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. Ari writes weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.