At the beginning of Mark Merlis' engrossing, ambitious new novel, we meet Martha, a 75-year-old illustrator. For decades she has lived alone in her New York City apartment, bearing the double loss of her son, killed in Vietnam, and her husband, Jonathan, who died of a stroke just a few months later.

At the beginning of Mark Merlis' engrossing, ambitious new novel, we meet Martha, a 75-year-old illustrator. For decades she has lived alone in her New York City apartment, bearing the double loss of her son, killed in Vietnam, and her husband, Jonathan, who died of a stroke just a few months later.

Now her routines—painting, walks, solitude—are interrupted when a young academic approaches her about writing a biography of her husband, an obscure writer who flared briefly into fame before being forgotten again after his death.

We quickly learn that her marriage was anything but idyllic. She married Jonathan after becoming unexpectedly pregnant; she refers to him early in the novel as “the-man-who-got-me-in-trouble.” Early in their marriage they come to a tacit agreement that each can seek intimacy outside of their marriage: Martha in the summers she spends outside of New York, Jonathan in the bars and alleyways he trawls for sex—often anonymous, sometimes purchased—with young men.

Their relationship is further strained when Jonathan begins writing openly about his erotic life, in what Martha calls a “ghastly little volume of poems” and in his single great novel. It's the erotic aspect of his work that—to Martha's dismay—attracts the interest of his would-be biographer, Philip, who tells Martha what it was like to discover Jonathan's poetry: “I opened this little book and there was a man telling in such a plain voice…the truth. I mean, my truth, a guy who could say outright what was beautiful in the world, which was the same as what I thought was beautiful.”

Martha's first impulse is to deny Philip access to Jonathan's papers, not least because she worries about how the book he's writing will treat her. “I am not a career widow,” she says, “I have made a life of my own. But it will end on the same page as Jonathan's.” Even so, she knows that a biography of Jonathan is the best chance she has of being remembered—and, more importantly, of preserving the memory of her son, Mickey.

And so Martha finds herself going through Jonathan's papers, which she hasn't seen for years, and reading for the first time the journals he kept. Merlis gives us these entries as Martha reads them, a formal conceit that allows us to share in Martha's discoveries. It also lets us hear Jonathan's voice and gives us access to the world that's changing so quickly around him.

The voice in the journals is thrilling: by turns angry, needy, lyrical, and longing. In the first entries, from 1964, Jonathan writes about the pre-Stonewall gay world in New York City, where he moves between salons full of urbane, literary men he envies and bars full of working-class men he desires. As years pass and gay men become more visible and politically organized, Jonathan feels ambivalence, even disgust: “Fairies are just the too richly feathered canaries in the mine,” he writes, “warbling the truth about all of us: that we don't believe in tomorrow.” At the end of his journal, in the early seventies, he's bewildered to find himself surrounded at the bars by men who are open about their identity; he tries “to just relax and practice not scowling at the gay people.”

Jonathan begins keeping a journal because he feels stymied as a novelist, and we follow him as he realizes that the subject of his next book will be the young men he longs for. The passages where Jonathan writes about his desire and his encounters are some of the best in the novel, lit with an electric longing, “an ecstatic hopelessness that was more like longing for God than longing for dick.” “I look at the emergent body of a boy stretching into a young man and see into the heart of the cosmos,” he says, though he will come to question his facility for turning sexual desire into metaphysics.

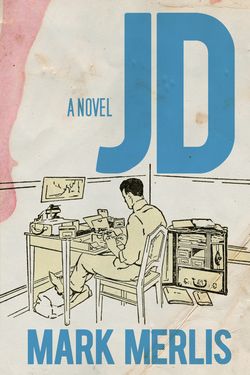

The title of Jonathan's great book, JD, stands both for “juvenile delinquent” and for James Dean. Martha calls it “a love song to baby-faced hoodlums”; for Jonathan, it's at once a hymn to “boys as they are now” and a dissection of “The tension between their…animal yearning” and “the monochrome, valueless world we expect them to grow into.”

The title of Jonathan's great book, JD, stands both for “juvenile delinquent” and for James Dean. Martha calls it “a love song to baby-faced hoodlums”; for Jonathan, it's at once a hymn to “boys as they are now” and a dissection of “The tension between their…animal yearning” and “the monochrome, valueless world we expect them to grow into.”

It's also, more than he realizes as he's writing it, a book for his son. Merlis' novel is deeply moving in its portrayal of Jonathan and Martha as they try to care for their child. They watch helplessly as he seems to slip through their grasp, failing out of school and spending his few waking hours smoking pot, until finally he's called up for the draft. “Some time in his teens,” Martha remembers of Mickey, “when he should have been white-hot with lust for the world, he forgot how to speak in the future tense.”

Reading Jonathan's journal, Martha will be shocked and acidic about what she sees as Jonathan's hypocrisy. “He railed against the society that drained the boys' manhood,” she says when she reads of his paying an underage hustler for sex, “and then knelt to catch the last drop.”

She will also learn a great deal about the years when her son withdrew from her, and about the possible causes for that withdrawal. She will be devastated by a shocking, heartbreaking act of trespass Jonathan commits, and she will also come to question her own role in her son's turning away from the future.

Both strands of Merlis' novel—Jonathan writing from the past, Martha speaking to us in the present—are vibrant, tense and alive. Merlis has written a profound book about sex and identity and family, about the perils of artistic ambition, about radical longing and the changing social fabric of America. JD is a beautiful novel.

Previous reviews…

Helen Humphreys' ‘The Evening Chorus'

Kim Fu's ‘For Today I Am A Boy'

Joyce Brabner's ‘Second Avenue Caper

Shelly Oria's ‘New York 1, Tel Aviv 0'

Garth Greenwell's debut novel, What Belongs to You, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux in early 2016. His short fiction has appeared in The Paris Review and A Public Space. He lives in Iowa City, where he is an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. Connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.