Follow Ari on Twitter at @ariezrawaldman.

NOTE: The announcement from the Attorney General's Office on DOMA is HERE.

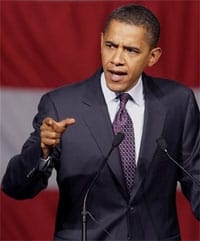

President Obama has instructed the Department of Justice to stop defending Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which recognizes only opposite sex marriages for the purposes of federal law. The President has also stated clearly that he believes Section 3 is unconstitutional because the law does not pass heightened scrutiny. The Administration has previously defended DOMA under as rationally related to some legitimate government interest. As we have discussed before, that is the easiest standard to beat. But today, the President has stated that he does not believe such "rational basis review" is appropriate for laws that discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Instead, DOMA merits some higher level of scrutiny, a hurdle DOMA cannot pass.

President Obama has instructed the Department of Justice to stop defending Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which recognizes only opposite sex marriages for the purposes of federal law. The President has also stated clearly that he believes Section 3 is unconstitutional because the law does not pass heightened scrutiny. The Administration has previously defended DOMA under as rationally related to some legitimate government interest. As we have discussed before, that is the easiest standard to beat. But today, the President has stated that he does not believe such "rational basis review" is appropriate for laws that discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Instead, DOMA merits some higher level of scrutiny, a hurdle DOMA cannot pass.

This is a welcome (and, admittedly, somewhat surprising) development. The President has long stated his opposition to DOMA, but this marks the first time that the Administration has come out in favor of heightened scrutiny and the first time the Administration has stated that it will decline to defend the statute in court. The President deserves our wholehearted support and gratitude. This is an important first step in what has already been (and will continue to be) a long legal drama.

But, does this mark the end of DOMA? Not exactly.

I would like to take this opportunity to briefly state how and why this happened seemingly out of the blue and what this development means for DOMA going forward. Please use the comments for any additional questions or comments you may have.

Questions and answers, AFTER THE JUMP…

How did this happen? Why now?

Some time ago, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed two cases challenging DOMA in district courts in the Second Circuit. This was important because the Second Circuit (which covers New York, Connecticut and Vermont) had no binding precedent on what kind of standard of review to use for laws that discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. While I have argued that the Supreme Court has stated in Romer v. Evans and Lawrence v. Texas that rational basis review is the appropriate standard, I have also said that (a) Lawrence's standard is pretty unclear, (b) the issue in Romer was very different than the issues posed by DOMA, and (c) the Supreme Court never held explicitly that sexual orientation discrimination must get rational basis review, rather the Court decided Romer and Lawrence this way: regardless of what standard these statutes get, they do not even pass rational basis review, so they are unconstitutional under any standard.

Since the Second Circuit never took a position on the appropriate standard, the ACLU cases offered the Administration the opportunity to argue the position it preferred. President Obama has decided that he believes that because of a history of discrimination against gays and lesbians (as well as other factors), heightened scrutiny is the best way forward.

What does heightened scrutiny mean?

In this case, heightened scrutiny likely means that a statute must further "an important government interest in a way that is substantially related to that interest." That is a tougher standard to meet than rational basis review, which just requires a statute be rationally connected to a less important interest. I say "likely" because the Administration's press release simply referred to "some level of heightened scrutiny," which could be this intermediate scrutiny or strict scrutiny. There is some precedent for applying strict scrutiny — furthering a compelling government interest in a narrowly tailored way — from some federal courts and state courts. But, I believe intermediate scrutiny is a more likely result, as a number of federal and state courts have found gays to be "quasi-suspect classes."

As a practical matter, this means that if the court adopts heightened scrutiny, it will be harder for DOMA to withstand constitutional scrutiny.

Will the Second Circuit accept heightened scrutiny?

It may, but not necessarily. While the Second Circuit has never explicitly set forth a standard of review for laws that discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation, that circuit does not exist in a vacuum. When the parties argue their positions, the court will consider those positions and look at what other courts have done. This is called "persuasive precedent" — not binding, but persuasive.

Also, the Administration is not the final word on this matter. Given that the Administration will now decline to defend DOMA, Congress now has the right and opportunity to step into the shoes of the DOJ to defend legislative enactments in court. This means that by the time briefing occurs in this case, the court will have a wide range of options.

Is DOMA dead?

No, for a few reasons.

First, this is just the Administration stating its legal position. Even if the Administration was the only party arguing in these Second Circuit cases, the court does not have to adopt the Administration's opinion.

Second, the Administration will not be the only one defending DOMA. As you can see from the press release, the DOJ has notified members of Congress of the Administration's decision not to defend DOMA. Congressional leaders are permitted to step into the shoes of the DOJ to defend duly enacted federal laws passed by Congress. While Congress is split between majority Democrats in the Senate and majority Republicans in the House, it is likely that Republicans will seek to defend DOMA and argue before the Second Circuit that rational basis review is the appropriate standard of review.

Third, even if the Second Circuit accepts heightened scrutiny and declares DOMA unconstitutional, this will set up splits between the circuits on both the constitutionality of DOMA and on the appropriate standard of review. Therefore, these cases will likely go all the way up to the Supreme Court before there is a definitive and final judicial ruling on the constitutionality of DOMA. In fact, the Supreme Court may have to hear these cases twice, remanding the case for review based on a clear standard of review and, perhaps, hearing the cases again using that standard.