As the plaintiffs, attorneys, and assorted celebrities filed into the grandiose Supreme Court building at One First Street, you could get the feeling — even from afar — that something special was happening today. Paul Katami and Jeff Zarrillo walked in holding hands, as did Kris Perry and Sandy Stier. Ted Olson looked prepared and at ease, exactly what you would expect from a man who has argued more cases in front of the Supreme Court than he probably cares to count. In short, the day was momentous. Would the argument be, as well?

As the plaintiffs, attorneys, and assorted celebrities filed into the grandiose Supreme Court building at One First Street, you could get the feeling — even from afar — that something special was happening today. Paul Katami and Jeff Zarrillo walked in holding hands, as did Kris Perry and Sandy Stier. Ted Olson looked prepared and at ease, exactly what you would expect from a man who has argued more cases in front of the Supreme Court than he probably cares to count. In short, the day was momentous. Would the argument be, as well?

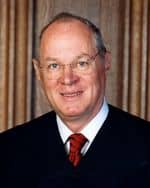

In a word, yes. I will let the prognosticators prognosticate, but what I would like to offer you is a legal perspective. The argument exceeded my expectations in terms of the questions the justices posed to counsel on both sides and what those questions might say about the justices' concerns. But, let's be clear: While the media have already taken to Twitter and their own websites to predict that this or that question from Justice Kennedy means that he will make this or that decision, those predictions often fall far south of meaningful. Any lawyer who has argued before a "hot bench" — namely, active questioners — knows that sometimes, especially in politically charged environments, judges of all stripes challenge both sides. In fact, a study of decades of Supreme Court arguments based on the number of hostile questions a given justice asked a given party showed no statistically significant correlation with that justice's ultimate decision in the case (notably, there was a statistically significant relationship found between softball questions and a favorable decision).

The actual hearing can tell us a few things, like what is on the justices' minds. Was Justice Kennedy mostly concerned about standing, or was he asking a lot of questions about equal protection? If a justice only asks about one issue, that's the one he or she is focused on. Did the Chief Justice ignore the scrutiny question and focus on how the case is really only about the word "marriage"? If so, that might only mean that he has no questions on standing, that he already made up his mind, and not necessarily that he thinks the Prop 8 proponents actually had standing.

With that in mind, follow me AFTER THE JUMP for the first of two posts offering a chronological summary and analysis of some of the more important highlights of the argument. When we all have had time to sit back and reflect, we will post a thematic analysis around the substantive questions in this case: standing, scrutiny, and equal protection.

CONTINUED, AFTER THE JUMP…

Charles Cooper, Prop 8 Proponents' attorney, struggles.

The day began with the attorney for the Prop 8 Proponents, Charles Cooper, having a rough start. He stumbled a bit in his opening, only to receive what can charitably be called "skeptical" questions from Justices Kennedy, Ginsburg, and Sotomayor. Justice Kennedy asked a poignant question about the 40,000-odd children in California who want their parents married, arguing that "those childrens' voices are important in this case." Mr. Cooper evaded, unwilling to say that children are irrelevant, but equally unwilling to concede that their parents deserve any recognition of their union.

The day began with the attorney for the Prop 8 Proponents, Charles Cooper, having a rough start. He stumbled a bit in his opening, only to receive what can charitably be called "skeptical" questions from Justices Kennedy, Ginsburg, and Sotomayor. Justice Kennedy asked a poignant question about the 40,000-odd children in California who want their parents married, arguing that "those childrens' voices are important in this case." Mr. Cooper evaded, unwilling to say that children are irrelevant, but equally unwilling to concede that their parents deserve any recognition of their union.

But all of that happened after Chief Justice Roberts stopped Mr. Cooper at his 34th word, asking that the attorney address the standing problem. Justice Ginsburg was skeptical of standing, setting Mr. Cooper up with a series of questions and pushing him to admit that granting standing in this case would be unprecedented. What makes your clients so special, the Chief Justice asked (paraphrased)? How are "your clients different from" any other random citizen of California who happens to like Prop 8? Justice Sotomayor, a lion of a questioner even in her appellate court days, was so dissatisfied with Mr. Cooper's answer to the Chief Justice that she asked again, seeking a specific "injury" the Proponents faced, much like teachers narrow questions to their students to make them easier. Mr. Cooper shot back with the Ninth Circuit's standing argument: that Proponents need not show their own direct injury, just injury to the state and a state right to step into the shoes of the California government.

The Chief Justice mercilessly put an end to this, encouraging Mr. Cooper to move on to the merits. Then came a question from Kennedy and then one from Ginsburg. Mr. Cooper was not only unable to make his argument, but struggled to return to his outline upon finishing his generally evasive answers.

The Chief Justice mercilessly put an end to this, encouraging Mr. Cooper to move on to the merits. Then came a question from Kennedy and then one from Ginsburg. Mr. Cooper was not only unable to make his argument, but struggled to return to his outline upon finishing his generally evasive answers.

Don't read too much into that, though. The Chief Justice is playing a managerial, gate-keeping role here (at least, up to this point, and we're only about 10 minutes in). Anyone who argues before appellate courts has to expect to be interrupted; the key is to both answer the question directly and steer the conversation back to your points. That more than half the bench didn't let Mr. Cooper get a word of his own in before interrupting him is not so much evidence that they don't agree with him as evidence that they didn't like his answers.

Mr. Cooper brought up the Baker v. Nelson canard — namely, that because the Court said in 1971 than there was "no federal question" in Minnesota denying a marriage license to a gay couple, this case cannot proceed. Justice Ginsburg had a few words on that, reminding Mr. Cooper than 1971 was over 40 years ago, before the Court said that gender-based classifications (what Justice Ginsburg spent her career on) get heightened scrutiny and long before gays had a constitutionally protected right to be who they are.

During this line of questioning, Justice Kennedy asks Mr. Cooper if a gay marriage ban could be a gender-based classification. That argument isn't new: Alice can marry Bob, but Alice cannot marry Carrie. Alice could marry Carrie if Alice were a man. So, a ban on gay marriage is discrimination on the basis of sex. That argument has not been very successful in the federal courts, but I'm more interested in how Justice Kennedy asked the question. He said, "It's a difficult question that I've been trying to wrestle with," and I believe him. Justice Kennedy, like the Chief Justice, is a thoughtful conservative scholar. He has shown favor toward gay rights cases in the past, but alongside his generation, he is struggling with society advancing and changing. Like Rob Portman, I think he is indeed struggling with this question, and the fact that he felt the need to express append this rather emotional postscript to his question is telling.

During this line of questioning, Justice Kennedy asks Mr. Cooper if a gay marriage ban could be a gender-based classification. That argument isn't new: Alice can marry Bob, but Alice cannot marry Carrie. Alice could marry Carrie if Alice were a man. So, a ban on gay marriage is discrimination on the basis of sex. That argument has not been very successful in the federal courts, but I'm more interested in how Justice Kennedy asked the question. He said, "It's a difficult question that I've been trying to wrestle with," and I believe him. Justice Kennedy, like the Chief Justice, is a thoughtful conservative scholar. He has shown favor toward gay rights cases in the past, but alongside his generation, he is struggling with society advancing and changing. Like Rob Portman, I think he is indeed struggling with this question, and the fact that he felt the need to express append this rather emotional postscript to his question is telling.

A few minutes later, Justice Sotomayor talks scrutiny, without using the words. She asks Mr. Cooper why the Constitution shouldn't treat gay people as a protected class. He responds by saying that the "class" of gays is amorphous, with homosexuality not immutable.

But it is Justice Kagan who gets Mr. Cooper to admit the central illogic of his argument. He says that allowing gays to marry does not serve the state interest in encouraging responsible procreation. Justice Kagan realizes Mr. Cooper is missing the point: "Is there any reason that you have for excluding them? In other words, you're saying, well, if we allow same-sex couples to marry, it doesn't serve the State's interest. But do you go further and say that it harms any State interest?" Mr. Cooper says yes because that would be redefining marriage. The end result of this less-then-one-minute exchange is that Mr. Cooper admitted that Prop 8 is not rationally connected to the legitimate state interest of encouraging heterosexuals to marry. He merely said gay marriage doesn't advance that particular interest, and the only so-called harm is this amorphous, imaginary concern about "redefining" marriage. Justice Scalia chimed in to give his "harms," at which point Justice Ginsburg shot back at him (as if ignoring Mr. Cooper). This is where this case will be won.

But it is Justice Kagan who gets Mr. Cooper to admit the central illogic of his argument. He says that allowing gays to marry does not serve the state interest in encouraging responsible procreation. Justice Kagan realizes Mr. Cooper is missing the point: "Is there any reason that you have for excluding them? In other words, you're saying, well, if we allow same-sex couples to marry, it doesn't serve the State's interest. But do you go further and say that it harms any State interest?" Mr. Cooper says yes because that would be redefining marriage. The end result of this less-then-one-minute exchange is that Mr. Cooper admitted that Prop 8 is not rationally connected to the legitimate state interest of encouraging heterosexuals to marry. He merely said gay marriage doesn't advance that particular interest, and the only so-called harm is this amorphous, imaginary concern about "redefining" marriage. Justice Scalia chimed in to give his "harms," at which point Justice Ginsburg shot back at him (as if ignoring Mr. Cooper). This is where this case will be won.

Justice Breyer gets the gold star for pointing out that infertile heterosexual couples marry all the time. The 52-year-old Justice Kagan, who isn't married and has no children, got a laugh when she asked about all those couples that are marrying after 55 and are producing "very few" children. And, the matriarch of a large family, Justice Ginsburg, raised the salient point about a case called Turner v. Safley, which guaranteed inmates the right to marry: they can marry she said, even when incarcerated and unable to have children. Mr. Cooper had the nerve to respond that there are very few, if any, cases where both persons in a heterosexual marriage are infertile because men can father children at almost any age. You could hear an audible groan from the audience at that one.

Then, Ted Olson came to the lecturn.

FOR PART 2 of the analysis, CLICK HERE…

LISTEN to the AUDIO and read the transcript of today's arguments HERE.

***

Ari Ezra Waldman teaches at Brooklyn Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. His research focuses on technology, privacy, speech, and gay rights. Ari will be writing weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues. You can follow him on Twitter at @ariezrawaldman.