In both the run up to and in the wake of historic Supreme Court arguments on gay equality (which you can read about here, here, here, here, and here), several political leaders from both parties have come out in favor of the freedom to marry. We've had Jon Huntsman, a Republican; Mark Begich, a Democrat; Rob Portman, a Republican; Hillary Clinton, a Democrat; Mark Kirk, a Republican; Bob Casey, a Democrat; and many others. And, they are just a tiny fraction of a fraction of the 58 % of Americans that now support our quest for marriage recognition.

Senators Begich, Portman, Kirk, and Casey are 4 among the 52 United States Senators — more than 1/2 of that august body — on the right side of history. Senator Tim Johnson, Democrat of South Dakota, is the latest, and Sen. Kirk is the latest Republican to buck the continued bigotry of his party's base and leadership, a position for which he deserves credit. But, let's not put the latecomers above the vanguard, like Senator Ron Wyden (pictured), a Democrat, who came out for marriage equality in 1995, before "marriage equality" was the de rigueur phrase and long before every other proud progressive felt comfortable following his lead.

Senators Begich, Portman, Kirk, and Casey are 4 among the 52 United States Senators — more than 1/2 of that august body — on the right side of history. Senator Tim Johnson, Democrat of South Dakota, is the latest, and Sen. Kirk is the latest Republican to buck the continued bigotry of his party's base and leadership, a position for which he deserves credit. But, let's not put the latecomers above the vanguard, like Senator Ron Wyden (pictured), a Democrat, who came out for marriage equality in 1995, before "marriage equality" was the de rigueur phrase and long before every other proud progressive felt comfortable following his lead.

Conservatives and liberals have blasted some our most recent allies as "phony" opportunists, spineless, or worse. Chief Justice Roberts even derisively characterized them as "falling over themselves" to support us. Others say we should welcome the evolution as either the nature of the political beast or the product of a personal journey. That's a discussion worth having, but at the moment, I am more interested in what got us here.

If you have been reading the news over the past two weeks, your head might be spinning from the tidal wave of pro-equality support. I mixed those metaphors for a reason: it's a surprisingly accurate description. One by one, many of our politicians have jumped on the marriage bandwagon. There were some important moments along the way — President Obama and Rob Portman come to mind — but the momentum reached a climax in the week leading up the Supreme Court hearings on Hollingsworth v. Perry, the Prop 8 case, and Windsor v. United States, the challenge to DOMA.

Timing was not our only ally; the law was, too. Federal court challenges to two harmful and discriminatory laws gave us the opportunity to replace the lies and fearmongering of the DOMA Congress and the Prop 8 proponents with truth and justice. And, the public learned, taking to heart the well-publicized lessons of court decision after court decision. Generational shifts are playing their role, but the law was the catalyst of the falling dominoes we read about every day. Hollingsworth and Windsor pushed public opinion, laying bare the emptiness of our opponents' arguments and the virulence of their hatred. There was little for politics to do other than to try and keep up.

I consider the catalytic effect of the law AFTER THE JUMP…

In previous columns, I have argued that even though legal decision-making is supposed to be insulated from the political winds of the day, politics can move law. Public opinion not only gives judges an indication of how well-received their decisions will be, but it can also give them license (and political cover) to make tough choices on divisive issues. Some judges explicitly consider versions of public opinion when they inquire into Congressional intent and consider the majorities that voted for a given piece of legislation that might be up for constitutional review. We saw Justice Scalia make counterintuitive use of Congressional majorities in the Voting Rights Act case, for example.

In previous columns, I have argued that even though legal decision-making is supposed to be insulated from the political winds of the day, politics can move law. Public opinion not only gives judges an indication of how well-received their decisions will be, but it can also give them license (and political cover) to make tough choices on divisive issues. Some judges explicitly consider versions of public opinion when they inquire into Congressional intent and consider the majorities that voted for a given piece of legislation that might be up for constitutional review. We saw Justice Scalia make counterintuitive use of Congressional majorities in the Voting Rights Act case, for example.

The judiciary is highly politicized, and contrary to nostalgic lamentations about modern hyperpartisanship, judicial nominations and judges' responsibilities have always been red meat for politics. Democratic-Republicans were furious with President Adams and the Federalists who pushed through the nomination of Chief Justice Marshall minutes before the end of the last Federalist majority in Congress. They, and their subsequent iterations, made judicial reform and nominations central pieces of their platforms.

Judges also reflect political changes in more subtle ways, declining to get too far afield from the vanguard of public opinion unless there is proof of an "emerging consensus" among the population about a particular issue. This is the reason Justice Scalia insisted on making the erroneous statement that sociologists are split on the issue of gay families. It also explains why Justice Alito said that gay marriage is younger "than cellphones" and why supporters of Prop 8 and DOMA warned against broad pro-equality rulings because the issue of marriage "is being worked out in the States." There is no "emerging consensus," they argue; we, like the experts, are wrestling with the issue, debating the laws and unsure of what to do.

Set aside the legitimacy of that view, which enforces a natural bias against judicial leadership and in favor of judicial submission to the elected branches of government, and notice how the opposite may be true in the case of the freedom to marry.

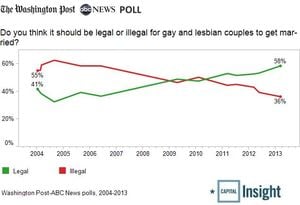

The media's favorite gay rights topic isn't substance; it's a process story about how fast public attitudes have changed over such a short time. If you look at the Washington Post's graph on the change over time, you will see opposition to marriage equality falling from about 60 to 48 percent from 2004 to 2009. There is no doubt that vigorous education campaigns contributed to that fall. But, between 2009 and 2010, public opinion reached a plateau, with opposition hovering around 48 to 50 percent, but not falling.

The media's favorite gay rights topic isn't substance; it's a process story about how fast public attitudes have changed over such a short time. If you look at the Washington Post's graph on the change over time, you will see opposition to marriage equality falling from about 60 to 48 percent from 2004 to 2009. There is no doubt that vigorous education campaigns contributed to that fall. But, between 2009 and 2010, public opinion reached a plateau, with opposition hovering around 48 to 50 percent, but not falling.

Then came the avalanche of court decisions striking down DOMA and Prop 8. In July 2010, Massachusetts Federal District Joseph Tauro struck down DOMA. Judge Vaughn Walker struck down Prop 8 in August 2010. Then came Edie Windsor's case and a similar challenge to DOMA in Connecticut. The Ninth Circuit then took down Prop 8. Out in San Francisco, Judge White declared DOMA unconstitutional shortly thereafter. And the dominoes kept falling as 23 bankruptcy court judges in Los Angeles joined a decision finding that DOMA is unconstitutional.

The media covered each decision and at each news spot, roundtable discussion, or talking head ping-pong match, mainstream and online media brought on legal and political experts. They talked about marriage and gay rights at length, forcing traditionalists into ever more desperate arguments that sounded more ridiculous every minute. The public was watching and taking note, realizing that the opposition to gays marrying was run by a cadre of bigots and realizing that there is nothing wrong with love.

Court cases laid bare the emptiness of opposition to the freedom to marry. Several powerful and well-argued cases at the front of our quest for equality put the question in stark terms of justice, without the cacophonous confusion of political campaigns and elections. It quickly became clear that a legal strategy must go hand-in-hand with a political strategy; one could not wait for the other.