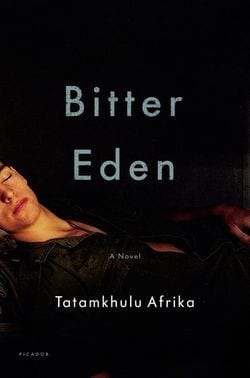

On the first page of Tatamkhulu Afrika's intense and passionate novel, the narrator, Tom Smith, receives a package from a man he hasn't seen in half a century. What it contains will send him back to the years he spent in Italian and German POW camps during the Second World War, camps that, for all their horror, Tom remembers as a “Bitter Eden.”

The book's depiction of the day-to-day life in those camps is extraordinary. Captured in Northern Africa, Tom finds himself in a desperate world of starvation and ingenuity, of lice and cigarette economies and amateur entertainments. It's “a place where anything unclaimed is everyone's prey,” and where in their hunger men become nothing more than “meat wanting more meat so that it can go on being meat.” It is a brutal place, and yet it allows for intimacies and affections the broader world prohibits.

The book's depiction of the day-to-day life in those camps is extraordinary. Captured in Northern Africa, Tom finds himself in a desperate world of starvation and ingenuity, of lice and cigarette economies and amateur entertainments. It's “a place where anything unclaimed is everyone's prey,” and where in their hunger men become nothing more than “meat wanting more meat so that it can go on being meat.” It is a brutal place, and yet it allows for intimacies and affections the broader world prohibits.

In this exclusively male world, men pair off with their “mates” to form ambiguous domestic relationships. The heterosexual Tom grudgingly allows himself to be claimed by Douglas, who disgusts him with his “almost womanliness,” and whose eagerness for Tom's friendship reminds him of “a drowning clown or a tart desperate for trade.” That such relationships are often sexual is an open secret, and Tom's cruelty to Douglas is a way of keeping at bay what he fears is Douglas's desire for more intimacy than he can offer.

This uneasy domestic arrangement is disrupted when Tom meets Danny, a British prisoner who makes Tom question what he thinks he knows about his own desires. “Sometimes I try to face up to the amorphous beast of how I feel,” Tom says, “lend it shape, substance, of which I can ask questions, have hope of a reply.” Increasingly anxious, he asks himself, “Am I one of them? Am I in love with a man?”

The triangle between Tom, Danny, and Douglas will eventually turn tragic, but the book is most interested in the love between Tom and Danny, which will surprise both of them with its ferocity. That intensity is reflected in Afrika's prose, which often takes on a hothouse lyricism that throbs with emotion.

In the book's most beautiful moment, Danny wakes Tom to an eerie midnight scene: “a host of thousands of us are standing between the huts, motionlessly and silently as though bewitched, faces upturned under the full moon to the flank of the nearby hill.” Tom is confused until he hears the song of a nightingale, whose beauty has drawn the men from their beds: “‘So small a throat!' I am thinking. ‘So small a throat!' as the soaring gusts of sound, pitched a note's breadth this side of sense, flood, copiously as the moon's light, effortlessly as that which needs no struggling breath nor fiddling hand, out over hills, churches, shrines, our ragbag selves.”

Afrika has a distinctive voice, a strange mixture of coarseness and composure, with a cadence informed by the Old Testament. At times, especially as he describes the deprivations of the camps, his sentences fall into a psalmic lilt: “and the skeletons we pretended we did not have begin to show, and our lips crack like the old mud's heaving apart, and our tongues are the tumescences our loins no longer need.”

While the book has met with great acclaim, some reviewers have complained that it suffers from melodrama, and it's true that Afrika is drawn to extreme situations and the emotions they evoke, emotions he isn't inclined to express with understatement. But I found myself increasingly entranced by this novel, which draws on Afrika's own experiences as a POW. In its final sections, which recount first a forced march and then Tom's initial days of freedom, including Danny's remarkable and surprising courage in facing up to what he feels, I found myself harrowed and extraordinarily moved.

While the book has met with great acclaim, some reviewers have complained that it suffers from melodrama, and it's true that Afrika is drawn to extreme situations and the emotions they evoke, emotions he isn't inclined to express with understatement. But I found myself increasingly entranced by this novel, which draws on Afrika's own experiences as a POW. In its final sections, which recount first a forced march and then Tom's initial days of freedom, including Danny's remarkable and surprising courage in facing up to what he feels, I found myself harrowed and extraordinarily moved.

Bitter Eden appeared in the UK in 2002, just weeks before Afrika's death. It has taken twelve years for the novel to reach the United States, and this very handsome hardcover edition is a labor of love for Stephen Morrison, the head of Picador, who wrote about the book's long journey in Publishers Weekly. American readers are lucky to have the chance to read this beautiful book, a record of a man's attempts to explore “the unpredictable thickets of my self,” where he finds that “a nothing that is everything is continuing to be said.”

Previous reviews…

Rabih Alameddine's ‘An Unnecessary Woman'

Edmund White's ‘Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris'

Randall Mann's ‘Straight Razor'

Janette Jenkins' ‘Firefly'

Garth Greenwell is the author of Mitko, which won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for both the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award and a Lambda Award. His new novel, What Belongs to You, is forthcoming from Faber/FSG in May 2015. He lives in Iowa City, where he is an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. Connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.