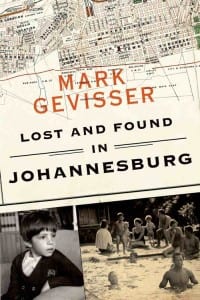

Mark Gevisser's extraordinary new book takes on several projects at once: It's a memoir of his own and his family's history; an exploration of the geography of Johannesburg, both human and natural; and an ambitious portrait of LGBT South Africans of all races both during and after the apartheid era. It's also the most exciting book of nonfiction I've read in a very long time.

It begins with a childhood game. In the 1970s, whiling away the hours of a privileged childhood, Gevisser would choose a name at random from the Johannesburg Telephone Directory, and then use his parents' street atlas to plot a route from his home to the stranger's address. But when he happened upon an African name in the directory, Gevisser found that his atlas provided no route between their neighborhoods, no way to plot a course from his bucolic suburb to the townships “where the black people who worked for us would go to church or to visit family on their days off.”

It begins with a childhood game. In the 1970s, whiling away the hours of a privileged childhood, Gevisser would choose a name at random from the Johannesburg Telephone Directory, and then use his parents' street atlas to plot a route from his home to the stranger's address. But when he happened upon an African name in the directory, Gevisser found that his atlas provided no route between their neighborhoods, no way to plot a course from his bucolic suburb to the townships “where the black people who worked for us would go to church or to visit family on their days off.”

And so Gevisser's game became a kind of political education, giving rise to a lifelong fascination with borders—how they are constituted and how they are crossed. What's most powerful in this very powerful book are the leaps it makes across its own boundaries, the connections Gevisser makes between his different projects of memoir and reportage. He finds “links between my own sense of alienation because of an illicit sexuality and the subordinate position of the majority of my compatriots,” and he tracks these connections through his personal history and the history and geography of his city.

As he pores over old maps, newspapers, and photographs, Gevisser realizes that “apartheid was embedded in the development of Johannesburg from the very start.” The very topography of the city—marked by hills formed by gold mining and sinkholes where the honeycombed terrain caves in—inscribes a social structure in which the subterranean many work for the obscene benefit of the few. In its carefully enforced boundaries, Johannesburg was “a world…defined by what it had been walled against, dammed against: I was safe in direct relation to the insecurity of those outside.”

Much of Gevisser's work as a journalist has focused on collecting the stories of LGBT people in South Africa, and he finds that it was often in queer communities that the lines so carefully policed in the larger society were crossed. White gay men hosted parties in their homes where men of all colors could congregate past curfew; at a beach popular among gay men, “white and colored or Malay men cruised across the color bar.” Hillbrow, a gay area, became “Johannesburg's first deracialized neighborhood in the 1980s.”

But Gevisser is careful not to romanticize this history: many gay whites fled Hillbrow once blacks moved in, and he makes clear how privilege, including protections for LGBT people, continues to be distributed with wild inequity. “You can rape me, rob me, what am I going to do when you attack me? Wave the Constitution in your face?” one black drag queen says to him in a moving passage about LGBT protections written into the South African constitution. “I'm just a nobody black queen.” But even in this case things are more complicated still: “She paused,” Gevisser goes on, “and then her face lost its mask of bravado and bitterness. ‘But you know what? Ever since I heard about that Constitution, I feel free inside.'”

Gevisser doesn't minimize the risks LGBT people still face in South Africa, especially the many LGBT immigrants who flee their own countries in hope of greater freedom. Instead, they find both that they are denied the protections offered to LGBT citizens, and that in addition to homophobia they face growing hatred of immigrants.

If the crossing of borders is often a liberating, even exhilarating prospect in these pages, it is also fraught with danger. Shortly before finishing this book, while he was visiting friends, Gevisser was the victim of a brutal, terrifying home invasion. This experience, which he alludes to in the book's first pages, hovers over everything he recounts. He is typically complex as he narrates it, terrified and enraged but also unwilling to dehumanize his assailants. “These were well-brought-up boys, once, before they became monsters, emasculated by poverty, by unemployment, by the culture of entitlement, by the AIDS epidemic, by the degradation of traditional life and the failure of urbanism to provide any sane alternative.”

If the crossing of borders is often a liberating, even exhilarating prospect in these pages, it is also fraught with danger. Shortly before finishing this book, while he was visiting friends, Gevisser was the victim of a brutal, terrifying home invasion. This experience, which he alludes to in the book's first pages, hovers over everything he recounts. He is typically complex as he narrates it, terrified and enraged but also unwilling to dehumanize his assailants. “These were well-brought-up boys, once, before they became monsters, emasculated by poverty, by unemployment, by the culture of entitlement, by the AIDS epidemic, by the degradation of traditional life and the failure of urbanism to provide any sane alternative.”

Gevisser's account of the remarkably varied shapes LGBT lives take in South Africa finally focuses less on the hardships they face than on the remarkable ways they manage, despite those hardships, to find whatever joy they can. It's impossible to do justice either to the scope of Gevisser's book or to my admiration of it in a short review. It accomplishes what I take to be the work of serious literature: it leaves me with a greater sense of marvel and compassion for the lives of others, a richer and more complex understanding of the world.

Previous reviews…

Emma Donoghue's ‘Frog Music'

Tatamkhulu Afrika's ‘Bitter Eden'

Rabih Alameddine's ‘An Unnecessary Woman'

Edmund White's ‘Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris'

Garth Greenwell is the author of Mitko, which won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for both the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award and a Lambda Award. His new novel, What Belongs to You, is forthcoming from Faber/FSG in May 2015. He lives in Iowa City, where he is an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. Connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.