In Brassaï's famous photograph, Lesbian Couple at Le Monocle, 1932, two women sit together at a shabby café table in Paris. One wears a dress, its thin strap twisted on her bare shoulder; the other, her hair in a short, masculine cut, is in a suit and tie, the collar of her shirt in disarray. They lean into each other and stare, seemingly engrossed, at something outside the frame, the fingers of the suited woman resting on her companion's elbow.

In Brassaï's famous photograph, Lesbian Couple at Le Monocle, 1932, two women sit together at a shabby café table in Paris. One wears a dress, its thin strap twisted on her bare shoulder; the other, her hair in a short, masculine cut, is in a suit and tie, the collar of her shirt in disarray. They lean into each other and stare, seemingly engrossed, at something outside the frame, the fingers of the suited woman resting on her companion's elbow.

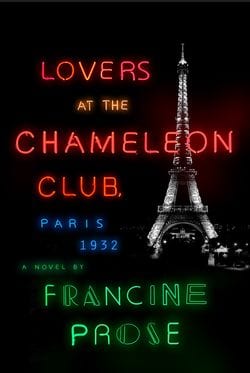

Francine Prose's engrossing, virtuosic new novel uses a fictional version of Brassaï's photograph to create a moving narrative of a group of friends and associates over two decades, as Paris devolves from the 1920s bohemian paradise of expatriate artists to the nightmare of rising fascism and Nazi occupation.

In Prose's version, the suited woman of the photograph is Lou Villars, a desperately unhappy former athlete who will become, thanks to the people she meets over the course of the novel, a nightclub performer, a racecar driver, a Nazi spy, a torturer. More than anything, she will be a tool, forever shaping herself to what she thinks are others' wishes, manipulated in ways she never fully sees.

Prose tells her story through a cast of revolving narrators, each of them connected somehow to that photograph: Gabor Tsenyi, the photographer who staged it; Lily de Rossignol, his patroness; Lionel Maine, an American novelist and his best friend; Suzanne Dunois, who will become Gabor's wife; and Yvonne, who owns the club where they all meet.

That club—the Chameleon Club of the title, named after the lizards Yvonne keeps as pets—serves as a barometer for political tensions in France. When we first see it, it's a place of remarkable tolerance, where men dress as women and women as men, where names are assumed and cast away, where sex and nationality are often uncertain; it's a place that calls into question the whole idea of fixed identity. Lily marvels at the performers Yvonne hires: “The beauty and style of those dancers! Watching them, I'd ponder what it meant, really meant, to be a man or a woman. Is it our clothes, our sexual parts, our bodies and brains and souls?”

Lou finds herself among those performers, after fleeing an abusive coach and, more importantly, a world that won't let her live as she wishes. She's one of the “strays” that Yvonne takes in, lost men and women “who found their way to the club after hearing that it was a refuge where you would be taken in and not asked any questions.” For a time she seems happy, falling in love with a fellow performer, Arlette, the first of several women who will break her heart.

Soon, however, the songs that Lou and Arlette perform take on a darker cast, bringing the audience to laughter with jokes about impotent immigrants and bumbling Jews. Yvonne and her dancers are harassed by the police. Lou becomes a target of the proto-Fascist police chief Clovis Chanac, Arlette's new beau, who is humiliated that his girlfriend once took Lou as her lover. The revenge Chanac takes—not least for the already famous, unerasable photograph Gabor took of Lou and the woman Chanac claims for his own—becomes part of the chain of indignities and resentments that will transform Lou from a Joan of Arc-worshipping nationalist to a traitor.

This ambitious novel paints a wide canvas, and doesn't shy away from the familiar figures and events of the Second World War—there's even a wonderful scene, at once chilling and ridiculous, with Hitler himself, who infects Lou with his crazed messianic fervor. But the real achievement of the book is that the intimate dramas of its characters' lives remain our chief concern, the medium through which we understand the horrors of war.

The book presents those dramas through a shifting set of documents in the characters' voices—letters, excerpts from memoirs and novels, newspaper articles—that often allow us to see the same event through multiple narrators' eyes. What might seem like a gimmick is instead consistently exciting, and offers the reader a fuller perspective on the complexity of events than any of the individual characters can have. At the same time, though, because there is no authoritative narrative voice—no third-person stand-in for the author—we're left finally in a morally compelling state of uncertainty.

The book presents those dramas through a shifting set of documents in the characters' voices—letters, excerpts from memoirs and novels, newspaper articles—that often allow us to see the same event through multiple narrators' eyes. What might seem like a gimmick is instead consistently exciting, and offers the reader a fuller perspective on the complexity of events than any of the individual characters can have. At the same time, though, because there is no authoritative narrative voice—no third-person stand-in for the author—we're left finally in a morally compelling state of uncertainty.

That uncertainty is most intense concerning the only character who doesn't get to speak in her own voice. Lou's story is told by a second-rate, present-day biographer, whose account is called radically into question by the novel's end. This is a canny move on Prose's part, since it allows her to put forth various theories about Lou's descent into what can only be called evil—her early family life, her disappointments in love, her public humiliations—while also insisting that such a descent finally escapes explanation.

Denying us direct access to Lou only makes her a more powerful presence in the narrative, while also ensuring that our primary attention and compassion remains with those who, bravely and foolishly, in ways insignificant or profound, stand against the tide of inhumanity by which she is swept up. Prose is among our most distinguished writers, and this may be her finest book. It's rare to find a novel that is at once so entertaining, so smart, and so serious in its moral scope.

Previous reviews…

Mark Gevisser's ‘Lost and Found in Johannesburg: A Memoir'

Emma Donoghue's ‘Frog Music'

Tatamkhulu Afrika's ‘Bitter Eden'

Rabih Alameddine's ‘An Unnecessary Woman'

Garth Greenwell is the author of Mitko, which won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for both the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award and a Lambda Award. His new novel, What Belongs to You, is forthcoming from Faber/FSG in May 2015. He lives in Iowa City, where he is an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. Connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.