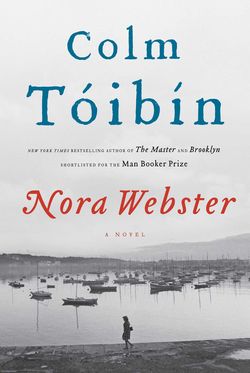

It's hard to explain the speed and excitement with which I turned the pages of the Irish writer Colm Tóibín's astonishingly beautiful new novel. Nothing extraordinary happens in it, at least at the level of plot, and it's almost free of the large-scale dramas that usually unify novels and give them their tension and forward momentum.

Instead of those dramas, Nora Webster offers not just the texture but the shape of what we might call daily life: quotidian events and minor crises swell and then ebb away, without anything building to a life-altering climax. How to understand, then, the profound changes undergone by its protagonist, or—rarer still—how deeply I was moved when I reached the final pages?

Instead of those dramas, Nora Webster offers not just the texture but the shape of what we might call daily life: quotidian events and minor crises swell and then ebb away, without anything building to a life-altering climax. How to understand, then, the profound changes undergone by its protagonist, or—rarer still—how deeply I was moved when I reached the final pages?

When the book begins, Nora Webster has just lost her husband to cancer. This novel is perhaps the most careful and revelatory study of character I have read, but such is Nora's—and Tóibín's—reticence that only slowly, over the course of the novel, do we realize how profoundly she loved her husband and how devastated she is by grief, how pain has separated her from the people she loves and undermined the certainties of her life.

Instead of grand gestures of mourning, the opening chapters concern themselves with the petty annoyances of living in a small town. The book is set in Wexford, Ireland, where Nora is surrounded by people she has known since childhood. “She knew the story of her life,” Nora thinks about one woman, “down to her maiden name and the plot in the graveyard where she would be buried.”

Nora has to defend herself against both the sympathy and the prying of the town, carving out a privacy in which she can learn how to bear her new circumstances. “She would learn how to spend these hours. In the peace of these winter evenings, she would work out how she was going to live."

Part of what this means is learning how to relate to her children again, who have changed in the months that she spent caring for her husband as he died. Her daughters are away at school, and during their visits she finds herself excluded from a new intimacy they have forged. “It was like being in a room with people who knew each other in ways that she did not, who had a language in common but, perhaps more importantly, could understand each other's silence.”

Her two young sons return from the house of the aunt who kept them, and since they don't speak of their father Nora doesn't understand at first how deeply they are grieving. But Donal, the older of the two boys, wakes at night screaming with nightmares, and Nora discovers that he has been bullying his younger brother. The book is deeply moving in its portrayal of Nora's bewilderment as a single parent: “She did not know whether it was better for him to cry or not to cry,” Nora thinks at one point about Donal. “Someone would know that, she thought, but she did not.”

Nora returns to work for the first time since her marriage, and with financial independence comes, very slowly, a new confidence and eagerness for life. “It pleased her now to be grateful to no one,” she thinks at one point, as she begins to explore new interests and to discover a new strength. She learns almost not to care about the gossip she knows her actions provoke, and, having established her privacy, she learns how to engage with her family and neighbors in a more authentic and nourishing way.

Most profoundly, Nora finds a way toward a new life through music. Her mother had been a singer, and in the months after her husband's death (the book covers a period of about three years), Nora begins taking singing lessons. She sings Irish songs, but also Schubert and Brahms, and at meetings of the Gramophone Society, a group of classical music lovers a friend encourages her to join, she discovers a depth of response to music that suggests to her possibilities for life she had never considered.

As she listens to a Beethoven trio, Nora “thought how easy it might have been to be someone else, that having the boys at home waiting for her, and the bed and the lamp beside her bed, and her work in the morning, were all a sort of accident. They were somehow less solid than the clear notes of the cello that came through the speakers."

As she listens to a Beethoven trio, Nora “thought how easy it might have been to be someone else, that having the boys at home waiting for her, and the bed and the lamp beside her bed, and her work in the morning, were all a sort of accident. They were somehow less solid than the clear notes of the cello that came through the speakers."

The end of the novel doesn't offer any final resolution of Nora's troubles and dissatisfactions; there's no tidy summing up of lessons learned. Nora hasn't healed from her husband's loss, but she is a changed person from the woman we met in the first pages, able now to face both her grief for the dead and her responsibilities to the living.

Colm Tóibín has already written, The Master and Brooklyn, two of my favorite novels of the last decade, and his essay collection, Love in a Dark Time: Gay Lives from Wilde to Almodóvar, is essential reading. But Nora Webster is an even greater achievement than those earlier books. Tóibín has mastered a rare alchemy, somehow producing, again and again, a kind of quiet sublimity out of the unvarnished moments of daily life. Read this book. I'm not sure art gets much better.

Previous reviews…

Saeed Jones's ‘Prelude to Bruise'

Michael Carroll's ‘Little Reef and Other Stories'

Francine Prose's ‘Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932'

Mark Gevisser's ‘Lost and Found in Johannesburg: A Memoir'

Garth Greenwell is the author of Mitko, which won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for both the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award and a Lambda Award. His new novel, What Belongs to You, is forthcoming from Faber/FSG in 2015. He lives in Iowa City, where he is an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. Connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.