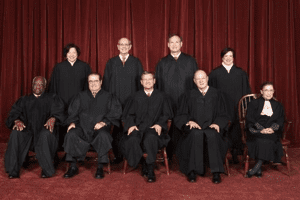

The media have been universally shocked at the Supreme Court's announcement today. Now that we have had time to read several media accounts (including our own Towleroad coverage) we should take a step back and analyze what this means from a legal, political, and practical perspective. I also would like to shed a little more light on how this may have happened and what conclusions, if any, we can draw from it.

Let's be clear on what did not happen. The Supreme Court did not make a substantive ruling on the constitutionality of banning gays from marrying. Nor did the Court make any ruling on the justice of marriage equality. The constitutional question lives on for another day.

Let's be clear on what did not happen. The Supreme Court did not make a substantive ruling on the constitutionality of banning gays from marrying. Nor did the Court make any ruling on the justice of marriage equality. The constitutional question lives on for another day.

The Court's denial of the petitions also has no explicit legal effect on anything other than those particular 7 cases for which it denied review and on the circuit court decisions below. It has, in the legal jargon, no precedential value: it does not compel any other court to make a certain decision in a certain way.

But it does represent the federal courts' final word on these cases. There are no more avenues of appeal for the anti-equality forces in Wisconsin, Indiana, Utah, Oklahoma, and Virginia, as well as in the other 11 remaining states covered by the Fourth, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits that do not already have marriage equality. That means that loving, committed gay couples can start marrying in those states very soon. Thanks to Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring, "soon" is now. Other states, especially those run by conservative, anti-gay governors, may try to defy the inevitable for as long as they can. But sooner rather than later, clerks from South Carolina to Wisconsin will be issuing marriage licenses to gay couples. They will be strengthening the institution of marriage in their states and throughout the country.

Many are wondering how this could have happened. Some commentators expected (more likely, hoped) that the Court would take at least one of these cases. Some expected the Court to do nothing. Back in June, I argued that there may never be a need for the Supreme Court to take a marriage equality case. I was alone in arguing that then, and there are now several commentators coming around to realize that possibility. The denials today only reinforce my point.

Follow me for one possible explanation for how and why this happened.

CONTINUED, AFTER THE JUMP…

There is now marriage equality in 24 states plus the District of Columbia. Marriage equality will soon come to 6 more states, from South Carolina to Wyoming, because those states are covered by the circuit court decisions that are now the final words on marriage equality in those jurisdictions. That is 60 percent of the states.

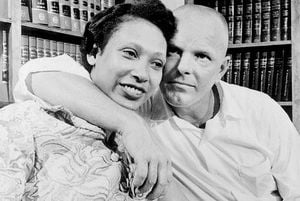

Twenty states will remain in a rump anti-equality dystopia. That number is special because it is quite close to the number of states (17) that still had bans on interracial marriage on their books when the Supreme Court decided Loving v. Virginia. That case declared all such bans unconstitutional. It reflected the views of the vast majority of the federal courts through the country. It reflected the views of the majority of Americans. It was fiercely opposed, especially in those 17 states in the South, but the notion that a state could ban blacks from marrying whites is so disgusting today that it is hard to believe even 17 banned the practice.

Twenty states will remain in a rump anti-equality dystopia. That number is special because it is quite close to the number of states (17) that still had bans on interracial marriage on their books when the Supreme Court decided Loving v. Virginia. That case declared all such bans unconstitutional. It reflected the views of the vast majority of the federal courts through the country. It reflected the views of the majority of Americans. It was fiercely opposed, especially in those 17 states in the South, but the notion that a state could ban blacks from marrying whites is so disgusting today that it is hard to believe even 17 banned the practice.

Before it took Loving, the Court waited. It had the opportunity to hear similar cases several times before jumping on the Loving bandwagon. It could have been because of the apt name; it could have been because some justices were waiting for a liberal majority. More likely, it was strategists on the Court waiting for the right case at the right time, when fewer and fewer states retained the bans. At that point, the country would be ready.

Today, the Court helped us along that road. Soon, marriage equality will become a non-issue. It already sort of is.

But the denials still shocked many. To me, it did not seem all that shocking.

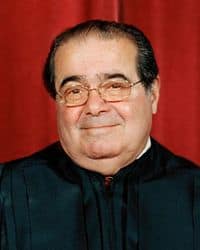

Taking a cue from one of my colleagues, who asked me to do the same: Put yourself in the shoes of one of the Supreme Court's conservatives. Let's say, Justice Scalia. Let's assume that Justice Scalia opposes extending the constitutional right to marry to gay persons. Here's what you know: You know you have four pro-equality justices against you. You have to know that Justice Kennedy is in their corner, too. So, you realize you have two options: Take the case and have five justices enshrine a federal marriage equality right in the constitution, or do not take the cases and swallow the lower court decisions. You hate the first option. The second option is somewhat better. At least, it keeps the case out of the Supreme Court.

Taking a cue from one of my colleagues, who asked me to do the same: Put yourself in the shoes of one of the Supreme Court's conservatives. Let's say, Justice Scalia. Let's assume that Justice Scalia opposes extending the constitutional right to marry to gay persons. Here's what you know: You know you have four pro-equality justices against you. You have to know that Justice Kennedy is in their corner, too. So, you realize you have two options: Take the case and have five justices enshrine a federal marriage equality right in the constitution, or do not take the cases and swallow the lower court decisions. You hate the first option. The second option is somewhat better. At least, it keeps the case out of the Supreme Court.

Conservatives like Scalia and Thomas do not want to touch marriage equality at the Supreme Court. Not only do they not want to lose, but they hate the idea of more federal rights, in general. Conservative jurisprudence is all about narrowing the federal Constitution, keeping people out, and letting legislatures answer problems. A federal appellate court saying gays have a federally protected right is bad enough. The Supreme Court saying the same thing is so much worse because it federalizes a right that Scalia doesn't think is there. So, if you're stuck with three circuits that have already rejected bans on gays marrying under the federal Constitution, you might as well let them stand with a simple denial without letting the Supreme Court "expand" the text of the Constitution.

That might explain why the conservatives didn't want to take the cases.

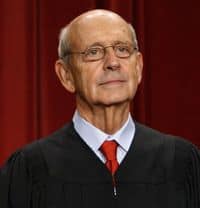

Now, imagine yourself in the shoes of a moderate like Stephen Breyer. You're cautious and approach your job with "judicial humility." You may not think the country is ready for a nation-wide right to marry for gay couples. You may want to hear from more courts, appellate or district, and more state legislatures. You may want to wait to take a case until you absolutely have to, i.e., when you have an appellate court decision upholding the constitutionality of a ban.

Now, imagine yourself in the shoes of a moderate like Stephen Breyer. You're cautious and approach your job with "judicial humility." You may not think the country is ready for a nation-wide right to marry for gay couples. You may want to hear from more courts, appellate or district, and more state legislatures. You may want to wait to take a case until you absolutely have to, i.e., when you have an appellate court decision upholding the constitutionality of a ban.

And, finally, imagine yourself in the shoes of a progressive justice like Ruth Bader Ginsburg. You have strong ideas about equality. Whenever the Supreme Court acts, you want it to be a lasting decision that will never erode and not face a backlash. You also do not feel compelled to take these particular cases because you agree with what happened below. You are comfortable waiting for the right time because you are not satisfied with a five justice majority. You want at least six. You realize that Justices Scalia and Thomas are lost causes. But you think that Chief Justice Roberts, a young man, is not going to be willing to oppose marriage equality and sit on a court for twenty more years. At that time, marriage equality will be as obvious as sliced bread. You want to build support from the ground up to peel off at least one more vote for marriage equality, and you're willing to wait to attack with overwhelming force.

Seen in this way, it is possible every justice voted against hearing these cases, but for different reasons.

***

Follow me on Twitter and on Facebook. Check out my website at www.ariewaldman.com.

Ari Ezra Waldman is a professor of law and the Director of the Institute for Information Law and Policy at New York Law School and is concurrently pursuing his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. Ari writes weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.