The final two virus strains thought to have made the cross-species jump from simians to humans and ultimately developed into HIV-1 have finally been identified. In order to understand the significance of the discovery, it’s important to understand where these two particular strains fall within HIV’s larger virological family tree.

Eight of the most broadly recognized strains of HIV are classified as HIV-2 and are commonly coded A-H. These various strains each sprung from individual human exposures to different strains of SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus) found in the sooty mangabey. As Robbie Gonzalez points out for io9, while there are many different strains of HIV-2, the virus is not commonly observed outside of West African countries and is markedly less virulent than HIV-1.

HIV-1, on the other hand, is far more common globally due to higher virulence and a larger volume of different mutations. Some of the variants like CRF19, an M-class strain, have proven themselves to be markedly more effective at infecting individuals at an accelerated rate. Unlike HIV-2 strains the M and N classes of HIV-1 are thought to have originated from human to chimpanzee contact in areas where the animals are sometimes hunted for consumption. The origin of the O and P classes, however, had proven much more difficult to trace back.

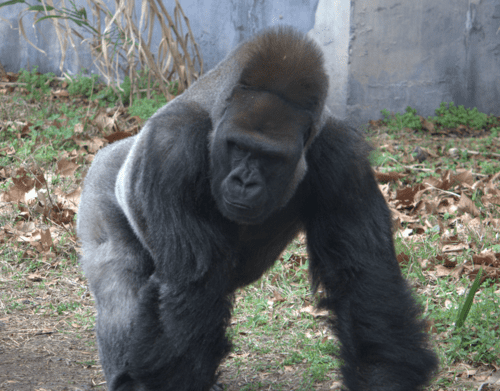

According to a study covered in the most recent issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of researchers from the French University of Montpellier have positively identified a link between the O and P classes of HIV and a form of SIV found in gorillas.

“Two fully sequenced gorilla viruses from southwestern Cameroon were very closely related to, and likely represent the source population of, HIV-1 group P,” the study’s abstract explains. “Most of the genome of a third SIVgor strain, from central Cameroon, was very closely related to HIV-1 group O, again pointing to gorillas as the immediate source.”

Pinpointing the organisms in which these two variants of HIV originated, explains the study’s lead virologist Martine Peeters, has allowed her team to more wholly understand the ways in which different HIV strains have had such different evolutionary paths.

In an interview with The New York Times Peeters lays out her team’s theory that gorilla-sourced strains of HIV were met with more biological barriers to entry–making it less prevalent in the human population–purely by chance:

“So why did the chimpanzee S.I.V. lead to a worldwide epidemic, while S.I.V. from gorillas morphed into a human virus that remained in one small country?

Both viruses then adapted to their new hosts. The human immune system can stop viruses like H.I.V. with a protein called tetherin, which links newly made viruses to the cell in which they formed. The “tethered” viruses are unable to escape to infect a new cell.

In their new study, Dr. Peeters and her colleagues found that the chimpanzee and gorilla viruses evolved different strategies for attacking tetherin. But only one got an excellent opportunity to spread.”