DPA

Children are playing football on a lawn, people are out walking, holding their faces up to the sun, dogs are sniffing trees, and a musician plays guitar on a bench.

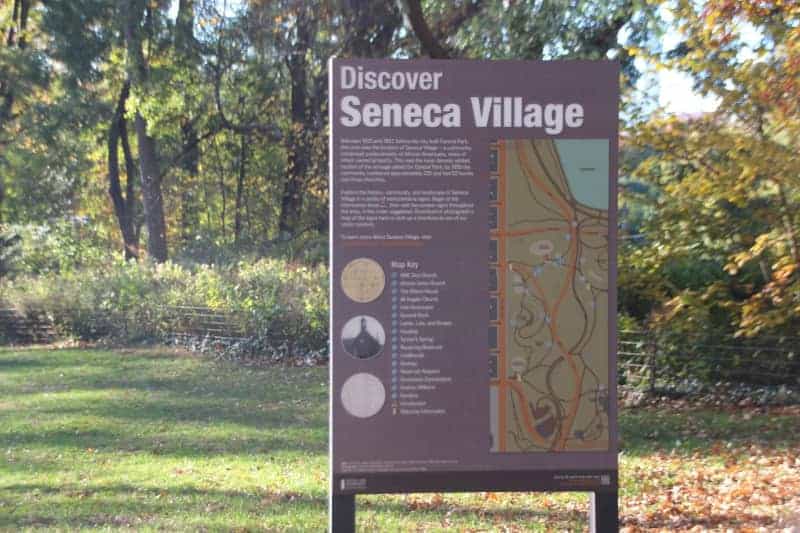

In the (often) harmonious everyday life of New York’s Central Park, a few brown signs on the mid-west side of the grounds rarely stand out.

“Discover Seneca Village” is written on them in white letters.

Central Park, which has served as a setting for countless Hollywood film scenes, is one of the most popular attractions in this city visited by more than 40 million people a year.

Largely shaped by the landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1876, the 3.5-square-kilometre park is an integral part of the cityscape today.

But Seneca Village, the first settlement of freed African-Americans in New York, had to make way for its creation.

Displaced and then forgotten

In 1825, owners John and Elizabeth Whitehead had divided their land – located roughly between 82nd and 89th Streets on the west side of what is now the park – into 200 lots and sold them.

Andrew Williams, a 25-year-old African-American shoeshiner, bought the first three lots for 125 dollars. Saleswoman Epiphany Davis later bought 12 plots for 578 dollars.

Over the years, a small settlement developed – consisting mainly of African-Americans who were freeborn or freed from slavery, as well as some Irish and German immigrants.

By 1850, the settlement already consisted of about 50 houses, three churches, graveyards and a school.

Seneca Village was one of the few African-American settlements at the time and allowed residents to live away from the heavily developed parts of southern Manhattan and away from the unhealthy conditions and racism that confronted them there, according to Central Park operators.

In 1857, however, the New York City Council decided to demolish Seneca Village and have Central Park built.

After that, the settlement was forgotten for a long time.

A few years ago, the park administration began to draw attention to the village’s former existence with signs – and now Seneca Village’s history is being revisited, directly opposite its former location, on the other side of Central Park in the renowned Metropolitan Museum.

“What might have been, had Seneca Village been allowed to thrive into the present and beyond?” ask curators at the Met with their exhibition “Before Yesterday We Could Fly.”

A one-room show in the Met

The show consists of only one room, but it is permanent – and plays with an established exhibition concept of the Metropolitan Museum, the so-called Period Rooms.

These are special rooms in the permanent exhibitions that are supposed to show visitors life in different times and places like 18th century France and ancient Rome with furniture, wallpaper and art.

These rooms have a “special magic,” as Vogue recently wrote – but until now they have dealt almost exclusively with the lives and works of white historical figures.

Now, for the first time, the Met has an “Afrofuturistic Period Room”, designed by production designer Hannah Beachler, who was involved in Beyonce’s music film project “Lemonade” and won an Oscar for her work on the film “Black Panther.”

“This project is important to me because it is a necessary conversation with time, loss, community and hope,” Beachler says.

The room offers an “important opportunity to start new dialogues and illuminate stories that are yet to be told within our walls,” Austrian museum director Max Hollein also said.

In this colourfully wallpapered space, a small house is suggested, filled with artworks and objects such as bowls and combs – inspired by objects from the real Seneca Village found in 2011 during excavations at Columbia University. A video installation runs alongside.

New York Times critic Salamishah Tillet lauded the Metropolitan Museum exhibition as “one of its most thoughtful reparations projects yet” – high praise for a museum often criticised for having a largely white, male perspective on the history of art.