Kevin Sessums last reviewed Come Back, Little Sheba and Next to Normal for Towleroad. You can also catch up with Kevin online at his own blog at MississippiSissy.com.

Kevin Sessums last reviewed Come Back, Little Sheba and Next to Normal for Towleroad. You can also catch up with Kevin online at his own blog at MississippiSissy.com.

I recently saw two productions of previous Pulitzer Prize winners in the Pulitzer's drama category — though neither is a drama. One is a a kind of Chekhovian comedy, that is if Anton Chekhov had read any Fannie Flagg. The other is a musical by Stephen Sondheim who, between perusing his famously dog-eared rhyming dictionary, seemed at the time to have been reading art history essays on neo-impressionism by the two Johns Rewald and Russell.

I recently saw two productions of previous Pulitzer Prize winners in the Pulitzer's drama category — though neither is a drama. One is a a kind of Chekhovian comedy, that is if Anton Chekhov had read any Fannie Flagg. The other is a musical by Stephen Sondheim who, between perusing his famously dog-eared rhyming dictionary, seemed at the time to have been reading art history essays on neo-impressionism by the two Johns Rewald and Russell.

Beth Henley's bittersweet Crimes of the Heart, which won the Pulitzer in 1981, has been revived at The Roundabout Theatre Company's Laura Pels Theatre. Actress Kathleen Turner is making her directorial debut with the production and she acquits herself admirably, mining the show's darker qualities while not skimping on the laughs embedded in the emotional mayhem that ensues when the three grown though not completely grown-up Magrath sisters congregate in their childhood kitchen in Hazelhurst, Mississippi. I'm a Mississippi native myself and one of my old Mississippi buddies, Johnny Epperson (AKA Lypsinka) is from Hazelhurst, proving that we shouldn't be shocked that this particular small town can be the breeding ground for such sweetly eccentric characters who bravely own their innate diva qualities.

Beth Henley's bittersweet Crimes of the Heart, which won the Pulitzer in 1981, has been revived at The Roundabout Theatre Company's Laura Pels Theatre. Actress Kathleen Turner is making her directorial debut with the production and she acquits herself admirably, mining the show's darker qualities while not skimping on the laughs embedded in the emotional mayhem that ensues when the three grown though not completely grown-up Magrath sisters congregate in their childhood kitchen in Hazelhurst, Mississippi. I'm a Mississippi native myself and one of my old Mississippi buddies, Johnny Epperson (AKA Lypsinka) is from Hazelhurst, proving that we shouldn't be shocked that this particular small town can be the breeding ground for such sweetly eccentric characters who bravely own their innate diva qualities.

The Magrath sisters were raised by their grandfather after their mother hung herself along with the family cat when they were children and he is now dying up at the town's hospital. One of the sisters — Meg — has flown in for the deathwatch from Los Angeles where she is a failed singer. The other two sisters still live in Hazelhurst. One — the mousy Lenny — is forlornly single and the other — the sensual yet ditzy Babe — has just shot her husband because she “didn't like his looks” and is now out on bail. Woven throughout all the play's woebegone kookiness is the noxious anger that is the residual result of their mother's suicide.

The Magrath sisters were raised by their grandfather after their mother hung herself along with the family cat when they were children and he is now dying up at the town's hospital. One of the sisters — Meg — has flown in for the deathwatch from Los Angeles where she is a failed singer. The other two sisters still live in Hazelhurst. One — the mousy Lenny — is forlornly single and the other — the sensual yet ditzy Babe — has just shot her husband because she “didn't like his looks” and is now out on bail. Woven throughout all the play's woebegone kookiness is the noxious anger that is the residual result of their mother's suicide.

Henley's most famous work is a maddening dramatic concoction that, like a souffle, seems so simple to get right yet often falls flat. Turner's production almost rises to the occasion. She has cast the play with three wonderful actresses. The tiny Jennifer Dundas as Lenny is just the dollop of emotional starch the play needs; there is nothing sentimental about what she achieves with the sentimental inchoate old-maid role. Lily Rabe, who is becoming one of New York's most reliable young stage actresses, strikes just the right notes of danger and ditz and downhome heartbreak as Babe. Sarah Paulson as Meg manages to be both off-puttingly condescending yet painfully needy at the same time. And I was especially taken by Chandler Williams who plays Babe's smitten lawyer, Barnette. In the original Broadway production the role was played by Peter MacNicol as a kind of nerdy joke. But Williams is surprisingly sexy, which is a good description of Turner's take on the play itself.

Henley's most famous work is a maddening dramatic concoction that, like a souffle, seems so simple to get right yet often falls flat. Turner's production almost rises to the occasion. She has cast the play with three wonderful actresses. The tiny Jennifer Dundas as Lenny is just the dollop of emotional starch the play needs; there is nothing sentimental about what she achieves with the sentimental inchoate old-maid role. Lily Rabe, who is becoming one of New York's most reliable young stage actresses, strikes just the right notes of danger and ditz and downhome heartbreak as Babe. Sarah Paulson as Meg manages to be both off-puttingly condescending yet painfully needy at the same time. And I was especially taken by Chandler Williams who plays Babe's smitten lawyer, Barnette. In the original Broadway production the role was played by Peter MacNicol as a kind of nerdy joke. But Williams is surprisingly sexy, which is a good description of Turner's take on the play itself.

T T 1/2 (out of 4 possible T's)

Crimes of the Heart, Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre, 111 West 46th St, New York. Ticket information here.

***SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE

Another Roundabout production, this one at the Studio 54 Theatre, is a revival of Sondheim's Sunday in the Park with George, which won the Pulitzer in 1985. It is a transfer from the highly acclaimed London production that originated at the tiny Menier Chocolate Factory Theatre before it moved to the West End where it won several Olivier Awards. The two leads from that production have recreated their roles here in New York City and the theatre season is richer for it.

Another Roundabout production, this one at the Studio 54 Theatre, is a revival of Sondheim's Sunday in the Park with George, which won the Pulitzer in 1985. It is a transfer from the highly acclaimed London production that originated at the tiny Menier Chocolate Factory Theatre before it moved to the West End where it won several Olivier Awards. The two leads from that production have recreated their roles here in New York City and the theatre season is richer for it.

Continued AFTER THE JUMP…

Mandy Patinkin and Bernadette Peters created the roles and I thought they could not be bettered. But their British counterparts now over two decades later, Daniel Evans and Jenna Russell, bring new dimensions to the dual roles that each plays in the musical's scheme. At their curtain calls at the matinee I saw, they blew the roof off the place as the audience rose in unison to give them a standing ovation and shouts of bravos. Evans in the roles of painter George Seurat in the first act set in 19th Century France and of his grandson George, a sculptor of light, set in the New York art world of the 1980s, is remarkable. He finds in each character the incongruent impetuses that make up an artist's swagger: an unbounded ego lashed to a lovely insecurity, a sweetness leavened with cynicism, a wanton addiction to the discipline of creativity. Russell is less sexy than Peters was in the role of Seurat's mistress, Dot, in the first act. But she is earthier and more moving. In the role of the grandmother Marie (the daughter of Seurat and Dot) in the second act, she is feisty and touching. The rest of the American cast is marvelous as well, especially Mary Beth Peil in her roles as the Old Lady in the first act and the art world aficionado, Blair Daniels, in the second, and Santino Fontana as the Soldier in the first act and, in the second, as Alex.

Mandy Patinkin and Bernadette Peters created the roles and I thought they could not be bettered. But their British counterparts now over two decades later, Daniel Evans and Jenna Russell, bring new dimensions to the dual roles that each plays in the musical's scheme. At their curtain calls at the matinee I saw, they blew the roof off the place as the audience rose in unison to give them a standing ovation and shouts of bravos. Evans in the roles of painter George Seurat in the first act set in 19th Century France and of his grandson George, a sculptor of light, set in the New York art world of the 1980s, is remarkable. He finds in each character the incongruent impetuses that make up an artist's swagger: an unbounded ego lashed to a lovely insecurity, a sweetness leavened with cynicism, a wanton addiction to the discipline of creativity. Russell is less sexy than Peters was in the role of Seurat's mistress, Dot, in the first act. But she is earthier and more moving. In the role of the grandmother Marie (the daughter of Seurat and Dot) in the second act, she is feisty and touching. The rest of the American cast is marvelous as well, especially Mary Beth Peil in her roles as the Old Lady in the first act and the art world aficionado, Blair Daniels, in the second, and Santino Fontana as the Soldier in the first act and, in the second, as Alex.

The first act of the musical still works better than the second, but the production's young British director, Sam Buntrock, who got his start in animation, brings an astonishingly fresh eye to the proceedings and utilizes his animator's expertise to the show's advantage. There are some breathtaking touches — visual punctuations that highlight the show's subject matter which involves the art of creation and how science can either enable it or deaden it, depending on your perspective. Seurat, in a letter stating his thoughts on the process, could have been summing up Sondheim's take on the making of his own art, when he wrote, “Art is Harmony. Harmony is the analogy of the contrary and of the similiar … considered according to their dominance … in gay, calm, or sad combinations.”

The first act of the musical still works better than the second, but the production's young British director, Sam Buntrock, who got his start in animation, brings an astonishingly fresh eye to the proceedings and utilizes his animator's expertise to the show's advantage. There are some breathtaking touches — visual punctuations that highlight the show's subject matter which involves the art of creation and how science can either enable it or deaden it, depending on your perspective. Seurat, in a letter stating his thoughts on the process, could have been summing up Sondheim's take on the making of his own art, when he wrote, “Art is Harmony. Harmony is the analogy of the contrary and of the similiar … considered according to their dominance … in gay, calm, or sad combinations.”

Two of the finest examples, in fact, of Sondheim's art and philosophy are found in this show, the songs, “Finishing the Hat” and “Move On.” And at the end of each of the acts there is the transcendent, “Sunday,” during which Seurat's masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, is assembled for our benefit in all its pointillist and, yes, human glory. To paraphrase Mama Rose in Gypsy, a character in another musical for which Sondheim wrote the lyrics to Jule Styne's score and Arthur Laurents wrote the book, in which perhaps Sondheim's philosophical take on art was summed up best: the audience can forgive you for a lot if you give 'em a great finish.

Two of the finest examples, in fact, of Sondheim's art and philosophy are found in this show, the songs, “Finishing the Hat” and “Move On.” And at the end of each of the acts there is the transcendent, “Sunday,” during which Seurat's masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, is assembled for our benefit in all its pointillist and, yes, human glory. To paraphrase Mama Rose in Gypsy, a character in another musical for which Sondheim wrote the lyrics to Jule Styne's score and Arthur Laurents wrote the book, in which perhaps Sondheim's philosophical take on art was summed up best: the audience can forgive you for a lot if you give 'em a great finish.

T T T T (out of 4 possible T's)

Sunday in the Park with George, Studio 54, 254 W 54th St, New York. Ticket information here.

***NOVEMBER

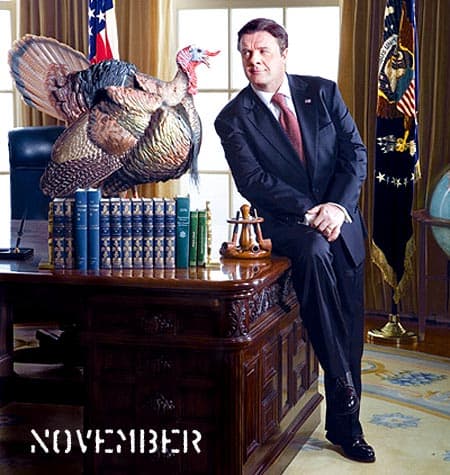

An Afterthought: If you're a Nathan Lane fan — and who really isn't — then perhaps you should catch him in David Mamet's afterthought of a play, November, at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre. Mamet won the Pulitizer Prize for Drama the year before Sunday in the Park with George did for his Glengarry Glen Ross. November won't win any prizes. But the audience howls with laughter at the vulgar language and hoary jokes with which Mamet has packed this sitcom of play about a Bush league president of the United States. The plot revolves around selling favors and pardoning turkeys and gay weddings. Lane gets every laugh — and even some that aren't in the script. Laurie Metcalf, as his lesbian speechwriter, is as expertly deadpan as Lane is in his frantic genius. The only real turkey on stage, however, is the play itself.

An Afterthought: If you're a Nathan Lane fan — and who really isn't — then perhaps you should catch him in David Mamet's afterthought of a play, November, at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre. Mamet won the Pulitizer Prize for Drama the year before Sunday in the Park with George did for his Glengarry Glen Ross. November won't win any prizes. But the audience howls with laughter at the vulgar language and hoary jokes with which Mamet has packed this sitcom of play about a Bush league president of the United States. The plot revolves around selling favors and pardoning turkeys and gay weddings. Lane gets every laugh — and even some that aren't in the script. Laurie Metcalf, as his lesbian speechwriter, is as expertly deadpan as Lane is in his frantic genius. The only real turkey on stage, however, is the play itself.

T (out of 4 possible T's)

November, Ethel Barrymore Theatre, 243 W. 47th Street, New York. Ticket information here.

Previous Reviews

On the Stage: Come Back, Little Sheba and Next to Normal [tr]

On the Stage: The 39 Steps and Almost an Evening [tr]

On the Stage: Is He Dead? and The Little Mermaid [tr]

On the Stage: Holiday Fare — The Drowsy Chaperone, West Side Story, Xanadu and The Color Purple [tr]

On the Stage: Doris and Darlene and The Homecoming [tr]