Kevin Sessums recently reviewed All My Sons, Speed-The-Plow and A Man for All Seasons for Towleroad. You can also catch up with Kevin online at his own blog at MississippiSissy.com.

Kevin Sessums recently reviewed All My Sons, Speed-The-Plow and A Man for All Seasons for Towleroad. You can also catch up with Kevin online at his own blog at MississippiSissy.com.

One of the great joys of attending off-Broadway productions is that one gets to discover amazing new actors and actresses and to rediscover others. Sometimes the plays even astound. But usually it's the performances that remain longer in the memory than the plays, which, more often than not, are written by promising playwrights at the beginnings of their careers.

Recently I've caught a few productions that contain some of the best performances I've seen in a few seasons. Let's start, however, with one that was not by a new playwright but by a veteran – David Rabe. His Streamers – the third play in his Vietnam trilogy which includes The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel and Sticks and Bones – is receiving a first-rate revival at the Roundabout Theatre's off-Broadway redoubt on 46th Street, the Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre. I saw the original production back in 1976 at the Mitzi Newhouse Theatre at Lincoln Center when Joseph Papp was serving as its producer as well as at his Public Theatre. I had only recently moved to New York and was “blown away,” to use the vernacular of the day, by that production, which was the first time I had ever seen and heard homosexuality discussed and displayed with such openness on a stage. The impact of seeing that performance lingers still. That 1976 production was directed by Mike Nichols – it transferred with some cast changes from the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven – and won the New York Drama Critics award for Best American Play that year, as well as a Drama Desk. It was nominated for a Tony in 1977 but lost to The Shadow Box.

Recently I've caught a few productions that contain some of the best performances I've seen in a few seasons. Let's start, however, with one that was not by a new playwright but by a veteran – David Rabe. His Streamers – the third play in his Vietnam trilogy which includes The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel and Sticks and Bones – is receiving a first-rate revival at the Roundabout Theatre's off-Broadway redoubt on 46th Street, the Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre. I saw the original production back in 1976 at the Mitzi Newhouse Theatre at Lincoln Center when Joseph Papp was serving as its producer as well as at his Public Theatre. I had only recently moved to New York and was “blown away,” to use the vernacular of the day, by that production, which was the first time I had ever seen and heard homosexuality discussed and displayed with such openness on a stage. The impact of seeing that performance lingers still. That 1976 production was directed by Mike Nichols – it transferred with some cast changes from the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven – and won the New York Drama Critics award for Best American Play that year, as well as a Drama Desk. It was nominated for a Tony in 1977 but lost to The Shadow Box.

It was, in fact, back in 1976, my first instance of seeing actors unknown to me who moved me beyond measure – especially the late Peter Evans, who later became a close friend of mine during his equally acclaimed performance in David Mamet's two-hander A Life in the Theater which costarred the legendary Ellis Rabb, at the then Theatre de Lys on Christopher Street. I followed Peter home one night around the corner from the theatre where he lived in a walk-up on Hudson. The next night I waited outside a store next door to his brownstone and pretended to be looking into its window and struck up a conversation with him when he was returning home from that evening's performance. We became instant friends and remained so for many years. Peter died of AIDS and his loss was not only a personal one, but an inestimable one to the theatrical community. One of the most moving moments I've ever spent in a theatre was his memorial service held at Playwrights Horizons, where he had scored another triumph in Jonathan Reynolds's Geniuses – which would be, come to think of it, another great play to revive in one of New York's off-Broadway theatres.

It was, in fact, back in 1976, my first instance of seeing actors unknown to me who moved me beyond measure – especially the late Peter Evans, who later became a close friend of mine during his equally acclaimed performance in David Mamet's two-hander A Life in the Theater which costarred the legendary Ellis Rabb, at the then Theatre de Lys on Christopher Street. I followed Peter home one night around the corner from the theatre where he lived in a walk-up on Hudson. The next night I waited outside a store next door to his brownstone and pretended to be looking into its window and struck up a conversation with him when he was returning home from that evening's performance. We became instant friends and remained so for many years. Peter died of AIDS and his loss was not only a personal one, but an inestimable one to the theatrical community. One of the most moving moments I've ever spent in a theatre was his memorial service held at Playwrights Horizons, where he had scored another triumph in Jonathan Reynolds's Geniuses – which would be, come to think of it, another great play to revive in one of New York's off-Broadway theatres.

At that memorial service, another of his good friends, Victor Garber, sang one of the most beautiful renditions of “No One is Alone” from Into the Woods I still have ever heard. After the service, his lover, director Gerald Gutierrez and best girlfriend, playwright Wendy Wasserstein, and I hoisted our drinks at Chez Josephine – all of us red-eyed from crying – to our beloved Peter and now they too, sadly, tragically, are gone. Forgive me for going on about Peter, but for those of you out there who might have known him, you'll understand. He was a gentle soul. And a giant talent. And deserves to be remembered.

Peter played Richie in that 1976 production of Streamers, which is the role of the urbane Manhattanite who is quite open about his homosexuality – especially for 1965 when the play is set and even more especially inside a Virginia army barracks where the action of the play takes place. The inchoate chaos of the Vietnam war hangs over the social chaos that is happening outside those barracks in the racially charged America of the time. The relationships of the soldiers in the close confines of the barracks highlight the chaotic tensions that were gripping the nation. Rabe, moreover, uses Richie's homosexuality to highlight the other social tensions that were straining society until there is a tragic eruption that is, indeed, warlike in its severity and shocking suddenness.

Peter played Richie in that 1976 production of Streamers, which is the role of the urbane Manhattanite who is quite open about his homosexuality – especially for 1965 when the play is set and even more especially inside a Virginia army barracks where the action of the play takes place. The inchoate chaos of the Vietnam war hangs over the social chaos that is happening outside those barracks in the racially charged America of the time. The relationships of the soldiers in the close confines of the barracks highlight the chaotic tensions that were gripping the nation. Rabe, moreover, uses Richie's homosexuality to highlight the other social tensions that were straining society until there is a tragic eruption that is, indeed, warlike in its severity and shocking suddenness.

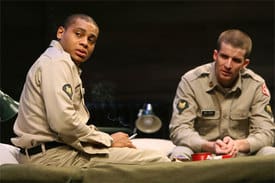

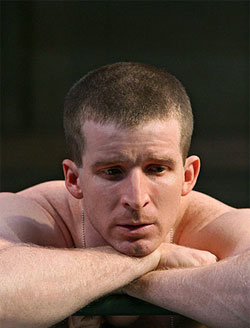

Richie is obviously in love with a fellow soldier, Billy, a mild-mannered midwesterner, who seems so confused by such affection that he can't completely rebuff it until it's too late. The other two main characters are African Americans – the go-along-to-get-along Roger and the temptestuous Carlyle, who understands Richie's carnal needs but cannot control his own more base ones. The performances in the Roundabout revival are all first-rate. Hale Appleman is making a stunning New York debut as Richie. There is a sly simplicity to his portrayal of the anything-but-simple Richie. And he is able to imbue Richie with a kind of tortured grace. It is a brave performance because it seems so lacking in bravery.

J.D. Williams as Roger is the most professionally adept of the actors in this production. There is a smoothness to him he is able to translate into the role itself. Brad Fleischer as Billy sometimes lets the character's own tentativeness spill over into his own talent. But Ato Essandoh as Carlyle – in a role that originally forever seared Dorian Harewood into my theatre-going mind – shows no tentativeness at all in delving deeply – and could it be? – heartbreakingly into his character's deepseated and appalling danger. Appleman and Essandoh are giving the kinds of performances that more than anchor this melodramatic play; they are giving ones that will be remembered by new theatregoers of 2008 as they watch them over the next few years mature into their stature as truly gifted stage actors.

J.D. Williams as Roger is the most professionally adept of the actors in this production. There is a smoothness to him he is able to translate into the role itself. Brad Fleischer as Billy sometimes lets the character's own tentativeness spill over into his own talent. But Ato Essandoh as Carlyle – in a role that originally forever seared Dorian Harewood into my theatre-going mind – shows no tentativeness at all in delving deeply – and could it be? – heartbreakingly into his character's deepseated and appalling danger. Appleman and Essandoh are giving the kinds of performances that more than anchor this melodramatic play; they are giving ones that will be remembered by new theatregoers of 2008 as they watch them over the next few years mature into their stature as truly gifted stage actors.

The title of the play comes from the soliloquy of one of the drunk sergeants who end each of the play's acts with their gruff and touching bluster. (In the original they were memorably played by Dolph Sweet and Kenneth McMillan and now are just as memorably played by John Sharian and Larry Clarke.) The title involves the term for parachutes that do not open but stream downward above the condemned man attached to them. And here's another detail, proof of what great roles Rabe has written in this play. The film version was directed by Robert Altman. Richie was played by artist Roy Lichtenstein's son, Mitchell; Billy by Matthew Modine; Carlyle by Michael Wright; and Roger by a very young David Allan Grier. At the Venice Film Festival, where the film premiered, the whole cast was awarded with the Best Actor award. Maybe the Obies or New York Drama Critics could give this cast – masterully directed by Scott Ellis – the same kind of honor this year.

The title of the play comes from the soliloquy of one of the drunk sergeants who end each of the play's acts with their gruff and touching bluster. (In the original they were memorably played by Dolph Sweet and Kenneth McMillan and now are just as memorably played by John Sharian and Larry Clarke.) The title involves the term for parachutes that do not open but stream downward above the condemned man attached to them. And here's another detail, proof of what great roles Rabe has written in this play. The film version was directed by Robert Altman. Richie was played by artist Roy Lichtenstein's son, Mitchell; Billy by Matthew Modine; Carlyle by Michael Wright; and Roger by a very young David Allan Grier. At the Venice Film Festival, where the film premiered, the whole cast was awarded with the Best Actor award. Maybe the Obies or New York Drama Critics could give this cast – masterully directed by Scott Ellis – the same kind of honor this year.

T T T 1/2 (out of 4 possible T's)

Streamers, Roundabout Theatre Co., Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre, 111 West 46th St., New York. Ticket information here.

***

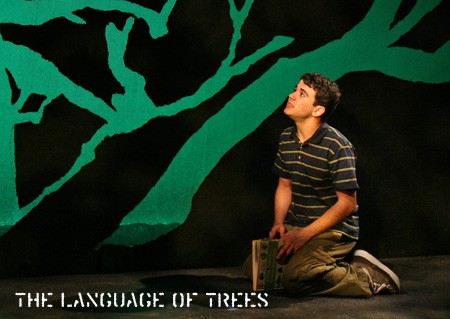

THE LANGUAGE OF TREES

Downstairs at the Roundabout's Steinberg Theatre, in the center's blackbox, is another play about war, The Language of Trees, written by recent Brown graduate Steven Levenson. The play is about the early years of the Iraqi conflict when a father and husband, played admirably by Michael Hayden, goes over to the Middle East to serve as a translator and is captured and tortured. There is a disjunctive quality to the play as it goes back and forth between where he is held captive and the life of his wife and child and their busybody neighbor back home. But perhaps such jarring disjunctiveness is the playwright's point. But it becomes even more pronounced when a kind of magical realism takes over in the war scenes as Bill Clinton joins the cell in which the translator is kept.

Downstairs at the Roundabout's Steinberg Theatre, in the center's blackbox, is another play about war, The Language of Trees, written by recent Brown graduate Steven Levenson. The play is about the early years of the Iraqi conflict when a father and husband, played admirably by Michael Hayden, goes over to the Middle East to serve as a translator and is captured and tortured. There is a disjunctive quality to the play as it goes back and forth between where he is held captive and the life of his wife and child and their busybody neighbor back home. But perhaps such jarring disjunctiveness is the playwright's point. But it becomes even more pronounced when a kind of magical realism takes over in the war scenes as Bill Clinton joins the cell in which the translator is kept.

The son left behind is seven years old but is played by an actor in his early 20s, Gio Perez. At first such casting just adds to all the disjunctiveness, but Perez is giving such a singular and unsentimental performance that I began to look past how weird it was to be watching him portray a child and realized that Perez and his director Alex Timbers had transformed that weirdness seamlessly into the performance of the precocious child himself. Perez is giving one of the most jaw-droppingly effective performances of anybody in New York right now. And it's great to rediscover Hayden, who has wowed me in the past as Billy Bigelow opposite Audra McDonald in the Lincoln Theatre Center production of Carousel and an earlier Roundabout production of All My Sons. Other fine work was done by Natalie Gold, as Hayden's wife and Perez's mother, Michael Warner as Clinton, and especially Maggie Burke as the neighborly busybody with a tragedy in her own life that she tries to numb by being so overly neighborly.

The son left behind is seven years old but is played by an actor in his early 20s, Gio Perez. At first such casting just adds to all the disjunctiveness, but Perez is giving such a singular and unsentimental performance that I began to look past how weird it was to be watching him portray a child and realized that Perez and his director Alex Timbers had transformed that weirdness seamlessly into the performance of the precocious child himself. Perez is giving one of the most jaw-droppingly effective performances of anybody in New York right now. And it's great to rediscover Hayden, who has wowed me in the past as Billy Bigelow opposite Audra McDonald in the Lincoln Theatre Center production of Carousel and an earlier Roundabout production of All My Sons. Other fine work was done by Natalie Gold, as Hayden's wife and Perez's mother, Michael Warner as Clinton, and especially Maggie Burke as the neighborly busybody with a tragedy in her own life that she tries to numb by being so overly neighborly.

I kept wondering though – during the play's repetitive moments – if Timbers had gotten a job directing a play with such a title because of his name instead of his brilliant work as Artistic Director of the inimitable off-Broadway company Les Freres Corbosier? Not a good thought to have when the play was trying so hard to move me with its theme of how grief is an isolating emotion that is so difficult to share. Or, as this lovely but flawed play attests, to transcribe.

Another explanation of a title. It comes from the Bertolt Brecht line: “What times are these when a talk about trees is almost a crime because it implies silence on so many wrongs.” The play, in which the translator convinces his young son that trees have a language all their own if we only listen to them closely enough, is more than an indictment of the Bush administration's geopolitics; it is a quiet cri-de-coeur of how the personal is always disquietingly political.

Another explanation of a title. It comes from the Bertolt Brecht line: “What times are these when a talk about trees is almost a crime because it implies silence on so many wrongs.” The play, in which the translator convinces his young son that trees have a language all their own if we only listen to them closely enough, is more than an indictment of the Bush administration's geopolitics; it is a quiet cri-de-coeur of how the personal is always disquietingly political.

T T (out of 4 possible T's)

The Language of Trees, Roundabout Underground, Black Box Theatre at the Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre, 111 West 46th St., New York. Ticket information here.

Next up: off-Broadway's Back Back Back and Farragut North – with more undiscovered actors as well actors, already discovered, who are proving why they were in the first place.

Recently Reviewed

On the Stage: All My Sons and Speed-the-Plow [tr]

On the Stage: A Man for All Seasons [tr]

On the Stage: Equus and The Seagull [tr]