I asked Moore about her engaging chemistry with Bening. She chalks it up to "luck! Stuart says I'm pansexual. He said, 'You have chemistry with Mark and Annette—that's because you're pansexual.' You have chemistry with somebody because of a certain kind of luck and I think desire, too, to make a connection onscreen."

I asked Moore about her engaging chemistry with Bening. She chalks it up to "luck! Stuart says I'm pansexual. He said, 'You have chemistry with Mark and Annette—that's because you're pansexual.' You have chemistry with somebody because of a certain kind of luck and I think desire, too, to make a connection onscreen."

Moore says the women's lesbianism itself means "everything and nothing, really…In terms of their being lesbians, I think the most interesting thing is that it's not commented on."

This was Cholodenko and Blumberg's intention from the very beginning—and their desire to make a connection with a wide audience has been giving The Kids Are All Right good chemistry with most film-festival patrons so far.

"I think as we continued to write, Stuart and I were really clear and became clearer that we wanted it to be, like, a not overtly political story," Cholodenko says. "That we wanted to focus on, you know, things that were much more universal and relatable, accessible, to more of a mainstream audience." This didn't preclude making gayness visible on the screen. "We wanted this to be a two-mom family and a gay family, with a sperm-donor father coming into the fold, and the way the plot kind of unwinds, you know, that [the sexualities of the leads] would almost be offhand or incidental."

The new Wendy & Lisa (actually, Lisa & Wendy, L to R).

But nothing about the making of the film was offhand; it took the writers years of rewrites to achieve the Oscar-bait script that was filmed. And nothing was incidental; in real life, Cholodenko and her partner Wendy Melvoin (of Prince's Wendy & Lisa fame) made use of a sperm donor to conceive their child, Blumberg donated sperm in college and in the same way that the women in the movie relied on a straight man to become moms, Blumberg was an essential ingredient in making Cholodenko's cinematic kid more than all right.

"That was the great thing about working with, you know, a straight guy that was kind of working in the mainstream, because I could trust that, you know, his barometer might be better than mine," Cholodenko says.

One use of Blumberg's barometer came when deciding whether to include a memorable scene that reveals the Bening and Moore characters get off watching gay male porn.

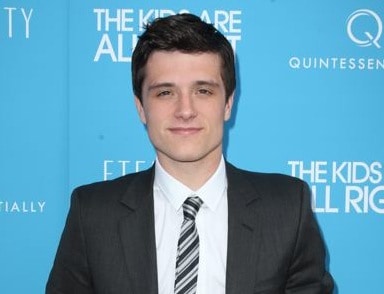

"I think it was even before Lisa and I decided to write this thing together in 2004," Blumberg (pictured) told me of the idea's genesis. "I think it was when [her feature] Laurel Canyon was coming out. I was at [a] café in L.A. called Victor's and I ran into Lisa and her partner Wendy and somehow it came out that occasionally they have been known to check out some gay male porn and I was like, 'Shut the front door! Wait, wait, let me just back that up…explain that to me?'"

"I think it was even before Lisa and I decided to write this thing together in 2004," Blumberg (pictured) told me of the idea's genesis. "I think it was when [her feature] Laurel Canyon was coming out. I was at [a] café in L.A. called Victor's and I ran into Lisa and her partner Wendy and somehow it came out that occasionally they have been known to check out some gay male porn and I was like, 'Shut the front door! Wait, wait, let me just back that up…explain that to me?'"

Blumberg later insisted it go into the script (Moore finds the scene "adorable"), over Cholodenko's initial objections.

"I was like, 'No, we can't put that in the script!' she recalls. "'We'll never get distribution. That's too, that's too out. That's just too much.' And he was like, 'No, no, no—it's funny! It's great, really—trust me, like, let's do that!' To me that seemed really…uhhh, 'Can't do that!'"

Blumberg's explanation for what made the script and what didn't, gay-wise, is, "If it felt organic to the moment and to the scene, we touched on it. But there was no sort of place for, 'Now we're gonna deliver our talk on this.' We really just tried to say, 'Let's figure out who this couple is, who this family is, at this point in time, take a snapshot—where are they?—and let's go from there.'"

I asked Cholodenko if she left anything out or put anything in to court a mainstream audience, to which she replied, "I think it was really just the focus on the inner life of these characters and being really clear about all their dimensions and their dilemmas and giving each one of them an arc, you know, and a place to begin and a journey to go through."

This led not only to juicy parts for even the supporting characters, but to parts which in their own right achieved the same appealing universality of the leading roles. YaYa DaCosta (pictured)—a runner-up on America's Next Top Model—turns in a sexy, earthy performance as Ruffalo's squeeze-of-the-moment and likens her character's race to the leads' sexualities.

This led not only to juicy parts for even the supporting characters, but to parts which in their own right achieved the same appealing universality of the leading roles. YaYa DaCosta (pictured)—a runner-up on America's Next Top Model—turns in a sexy, earthy performance as Ruffalo's squeeze-of-the-moment and likens her character's race to the leads' sexualities.

"I was a little surprised by how quickly I forgot that this was, as people like to say, an unconventional family," she told me of her first time seeing the completed film. "The fact that they're two mothers became so secondary to the rest of the story and you just forget…it's not about that, it's about all these other beautiful things. Just like I feel my blackness was secondary."

I asked 17-year-old Hutcherson his take on whether or not the gay aspect was beside the point in the film.

"What's cool about this film is it doesn't have a political agenda; it's not, like, slapping you in the face with it," he told me. "It's like, it's a family and, oh, yeah, by the way, they're lesbians. You know? Whatever. They could be anything. Even though it's not a political film, I kinda feel like by people seeing this and realizing that it's just a family, that will kind of maybe hopefully change people's minds."

"So far, we haven't encountered a whole lot of turbulence," Hutcherson says of the film's gay characters.

Hutcherson, a true millennial born and raised in (and still a resident of) Kentucky, told me his own approach to gay issues is informed by having many gay people in his life.

"I've always had open feelings about that. I come from a very, very liberal, welcoming, warm family; one of their foremost morals has been equal rights since I was little…People should be allowed to do and love and think and believe in whatever they want. There's a human right to love, and I feel like that's one that's so close to me because I had two gay uncles who unfortunately passed away of AIDS a while back. That being said, it just makes it even more relevant to me and makes it an even bigger issue I'm constantly fighting for."

The kids' individual interests in meeting their sperm donor flip-flop during the film.

Moore sees the film as a sign of the times. "I think films really tend to, rather than influence popular culture, I think they reflect culture," she says. "So the fact that we can have a movie like this means that this is kind of an ordinary American family. We're seeing this all over the United States right now. So that in and of itself, I think, is something."

Ruffalo, who only worked six days on the incredibly tight, 23-day shoot, agrees that the film is "apolitical" because, "Politics, I think, by nature, in order to survive, have to polarize people. Great filmmaking and storytelling brings people together."

One big, (sometimes) happy family.

Cholodenko's film certainly does that. In so doing, The Kids Are All Right makes an excellent argument that while "gay" does still matter, it's not the only thing that matters—and that "gay" and "straight" have more in common than most people on all sides of the issue are used to admitting.

I sometimes think the dividing line between reviling and embracing the concept of "post-gay" must run right down the middle of me, because people older than I am are more likely to turn up their noses at it and people younger than I am are more likely to live by it. My reaction to the post-gay outlook—in a nutshell, the concept that one's sexuality doesn't really matter anymore—is usually negative. I do think we are supposed to be working toward a world where sexual orientation doesn't matter; it's just that I continue to believe that asserting our society is post-gay is a lot easier to do from a gay haven like Manhattan or San Francisco. (And when ex-gays are on board with post-gay, it's time to recalibrate.)

I sometimes think the dividing line between reviling and embracing the concept of "post-gay" must run right down the middle of me, because people older than I am are more likely to turn up their noses at it and people younger than I am are more likely to live by it. My reaction to the post-gay outlook—in a nutshell, the concept that one's sexuality doesn't really matter anymore—is usually negative. I do think we are supposed to be working toward a world where sexual orientation doesn't matter; it's just that I continue to believe that asserting our society is post-gay is a lot easier to do from a gay haven like Manhattan or San Francisco. (And when ex-gays are on board with post-gay, it's time to recalibrate.)

For many people, for most, we are still in the pre-post-gay era.

Capitalizing on society's gay fatigue from the left and the right, Hollywood would love for us to believe all of its products are post-gay. But it's often grating when films are dishonestly marketed in such a way as to suggest that gay elements integral to the plot are really not what the films are about. "It's not just gay" is an irksome way of saying, "Please don't stay away from this movie just because it's gay, gay, gay—I could use your money." A Single Man, an (in my opinion) brilliant gay film by a gay director adapted from a gay novel written by Christopher Isherwood, one of our greatest gay writers, suffered from this misguided approach.

Moore says of her role, "I know plenty of gay families…it wasn't like I had to go out and do research."

But in Lisa Cholodenko's The Kids Are All Right (out—so to speak—in limited release July 9 and expanding thereafter), I think we've got a rare thing, a film that bridges the gay and post-gay worlds, a film that can be called gay, is genuinely not specifically about gay issues and should play very well with all but the most resolutely homophobic of audiences.

And best of all, it's a terrific story with great acting, some tears and lots of laughs. (My review here.)

Ruffalo & Moore attend a special NYC screening of the film. Photos from this event courtesy of Focus.

The movie, co-written by Cholodenko and Stuart Blumberg (The Girl Next Door, The Election of Barack Obama), stars Annette Bening and Julianne Moore as lesbian mothers of two teenagers, played by "It" girl Mia Wasikowska and up-and-comer Josh Hutcherson, who decide to hunt down the sperm donor who helped give them life. Mark Ruffalo plays their "donor dad," a man in his forties who's quite the opposite of the women whose family he helped make—he has no commitments and no family, so it's not so surprising he would covet the cozy family that comes calling. Bittersweet hilarity ensues.

The movie, co-written by Cholodenko and Stuart Blumberg (The Girl Next Door, The Election of Barack Obama), stars Annette Bening and Julianne Moore as lesbian mothers of two teenagers, played by "It" girl Mia Wasikowska and up-and-comer Josh Hutcherson, who decide to hunt down the sperm donor who helped give them life. Mark Ruffalo plays their "donor dad," a man in his forties who's quite the opposite of the women whose family he helped make—he has no commitments and no family, so it's not so surprising he would covet the cozy family that comes calling. Bittersweet hilarity ensues.

"I'm half a lesbian myself," Ruffalo admits. DVD-watch: "The ratings board gave us an X for one too many thrusts."

"What I love about the movie is it quickly transcends the novelty of the lesbian couple with teenage kids looking for the sperm-donor dad," Ruffalo said at a roundtable in Manhattan last week featuring all of the principals except for Bening (absent for personal reasons) and Wasikowska. "That's a great 'in' to a movie, but I've seen it with a few audiences now and what I responded to in the script is how much it felt like a couple that's been together a long time, whether they're straight or gay. And those teenagers are just like any teenagers trying to break away from domineering parents. [Bening and Moore], I felt they have that worn warmth and sort of simpatico and common dialogue that a long-time relationship has."

"What I love about the movie is it quickly transcends the novelty of the lesbian couple with teenage kids looking for the sperm-donor dad," Ruffalo said at a roundtable in Manhattan last week featuring all of the principals except for Bening (absent for personal reasons) and Wasikowska. "That's a great 'in' to a movie, but I've seen it with a few audiences now and what I responded to in the script is how much it felt like a couple that's been together a long time, whether they're straight or gay. And those teenagers are just like any teenagers trying to break away from domineering parents. [Bening and Moore], I felt they have that worn warmth and sort of simpatico and common dialogue that a long-time relationship has."