BY ARI EZRA WALDMAN

Ari Ezra Waldman is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. After practicing in New York for five years and clerking at a federal appellate court in Washington, D.C., Ari is now on the faculty at California Western School of Law in San Diego, California. His research focuses on gay rights and the First Amendment. Ari will be writing weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.

Follow Ari on Twitter at @ariezrawaldman.

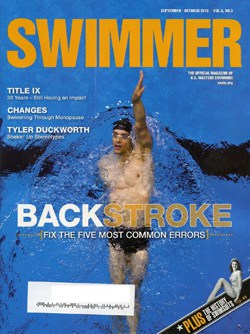

In October, Swimmer magazine profiled out swimmer and former Real World contestant Tyler Duckworth. He would probably be an Olympian by now were it not for a "freak accident" at school that broke his back, wrist and left heel. Still, Tyler recovered, excelled and competed at the Chicago Gay Games in 2006.

At least one reader did not like the fact that Swimmer magazine was "promoting homosexuality." Glenn from South Carolina wrote a letter to the editor stating that "[h]omosexuality is akin to thievery, adultery, and other sins that should not be tolerated or accepted … . Homosexuality destroys lives, individually, as well as that of the society as a whole. I am glad for the obvious success of Tyler Duckworth in the water but saddened to hear of his sinful homosexual lifestyle choice." Swimmer published the letter, right above two other letters celebrating diversity and the inclusion of gay swimmers in the community.

At least one reader did not like the fact that Swimmer magazine was "promoting homosexuality." Glenn from South Carolina wrote a letter to the editor stating that "[h]omosexuality is akin to thievery, adultery, and other sins that should not be tolerated or accepted … . Homosexuality destroys lives, individually, as well as that of the society as a whole. I am glad for the obvious success of Tyler Duckworth in the water but saddened to hear of his sinful homosexual lifestyle choice." Swimmer published the letter, right above two other letters celebrating diversity and the inclusion of gay swimmers in the community.

Glenn's letter caused a bit of an uproar. My friend Bradley, a leader of New York's gay swim team and an all-around awesome guy, gathered his friends to action condemning Swimmer for peddling homophobia and racism. He noted that free speech is one thing, but you would never see a magazine publishing a similar letter that spoke so hatefully about Jews or African-Americans, for example. Someone had to remind Swimmer that such language is no more worth publishing than racist diatribes from the Klan. Another friend of mine asked, "What kind of world do we live in where the First Amendment allows this to happen?" Another posted on Facebook, "There should be a law against this s**t!"

International Gay and Lesbian Aquatics (IGLA) agreed with Bradley, posting a sharp rebuke of Swimmer on its website. Swimmer posted a sincere apology: "We should have used better judgment during the editorial review of Mr. Welsford's letter. We could have asked him to resubmit his letter and made sure it met with stricter standards for such letters. And if we had deemed the second letter appropriate to print, we should have printed an explanation adjacent to it due to the sensitive nature of the topic. And we could have chosen to ignore the letter. While, again, we do not endorse or support Mr. Welsford's opinion, we respect his right or any other member's right to have an opinion on a topic we have introduced in the magazine and have it considered for publication."

I argue that this story is not about free speech — Glenn from South Carolina certainly has a right to an opinion, a right to write a letter expressing that opinion and a right to be free from any law that would punish him for either having his opinion or writing his letter. But, what is Swimmer's role in all of this? Does it have to give fair consideration to Glenn's letter? Or, is this question of what should Swimmer do, rather than what must it do? Let's consider what rights and responsibilities Swimmer has, AFTER THE JUMP…

Swimmer says that it respects all its readers' views, but used poor judgment in allowing Glenn's letter to get through.

What if Swimmer had a policy that said, "Swimmer magazine will not consider for publication any Letter to the Editor that uses racist, sexist, homophobic or other hateful language, the determination of which is solely at the discretion of the Editorial Board." Basically, Swimmer is saying that it will not publish what it considers hate speech. That seems like a reasonable policy for a private company to have. Swimmer, unlike a government entity, is basically free to determine what opinions it will voice in its publication. The First Amendment no more requires equal time or prevents it from publishing speech we don't like than it prevents or requires the New York Times from publishing columns by conservative columnists. No, this is question of Swimmer's sense of propriety — it might make the editorial choice that its commitment to diversity of views is more important than its commitment to diversity. What is clear is that this mini controversy was handled just the way it should be in our society: a homophobic letter appears in a publication; readers of that publication come together and advocate for a change in the publication's policies; the publication reconsiders its position and apologizes. That resolution is just as legitimate as one where the publication neither reconsiders its policies nor apologizes, resulting in a boycott by the offending advocacy group.

What if Swimmer decided it was not going to take any letters from conservatives, or from men, or from South Carolina? It would turn into Liberal Swimmer Monthly and would probably lose readers, but many of us would argue that it would not be doing anything illegal. And, what if Swimmer decided that it would only write about Neo-Nazi swimmers. I can't imagine it surviving as a for-profit publication, but again, would we want to narrow the First Amendment and not let the magazine function as a matter of law because it published an article entitled, "Jews and Gays Can Swim, But Not With Us"? I think many of us would prefer that its hate ruin it at the newsstand, rather than in the courtroom.

My question for you is: Do you want the law to play a role here? And, if so, what role? And, if not, what is the best response to hateful speech?

Law would play a role if Congress passed a law that "any media outlet that publishes anything that suggests homosexuality is sinful or a lifestyle choice shall be fined $5000." Many of us would jump up and argue that "hate speech" is not defined, that even if it were, the law amounts to viewpoint discrimination, and even if it is not viewpoint discrimination, we do not want (or need) this kind of law.

We are too keen to invoke the First Amendment as a sword and a shield. It neither twists our arms and forces us to publish or read hateful speech nor protects us from the court of public opinion when we do. Swimmer gets credit for admitting that publishing Glenn's letter was a matter of (mis)judgment; the magazine did not hide behind the First Amendment and argue that free speech allows it to publish whatever it wants. It recognized the difference between what it can do and what it should do.

Bradley gets credit for knowing that this issue is not about the boundaries of legal speech, but about an editorial policy he can get behind, lest his take his subscription fee elsewhere. But, those who decry the notion that a strong First Amendment makes Glenn's kind of speech possible and yearn for a regime where topics of conversation are simply off-limits in the public sphere are just begging for the devil they don't know.