Yesterday, Andy noted that Judge Vaughn Walker has responded to marriage equality opponents who have demanded that he return videotapes of the Perry v. Schwarzenegger Prop 8 trial that he has in his possession. In a letter to Molly Dwyer, Clerk of the Ninth Circuit Appeals Court, Judge Walker explained how he used and intends to use those video clips during his lectures.

Yesterday, Andy noted that Judge Vaughn Walker has responded to marriage equality opponents who have demanded that he return videotapes of the Perry v. Schwarzenegger Prop 8 trial that he has in his possession. In a letter to Molly Dwyer, Clerk of the Ninth Circuit Appeals Court, Judge Walker explained how he used and intends to use those video clips during his lectures.

Meanwhile, Prop 8 lawyers Theodore Olson and David Boies filed a motion yesterday to make all of the trial videotapes available to the public.

Walker's letter to Dwyer in its entirety:

This responds to a motion filed on April 13, 2011, by appellants-defendant-intervenors in Perry v Schwarzenegger, No 10-16696. It should be presented to the panel considering the motion.

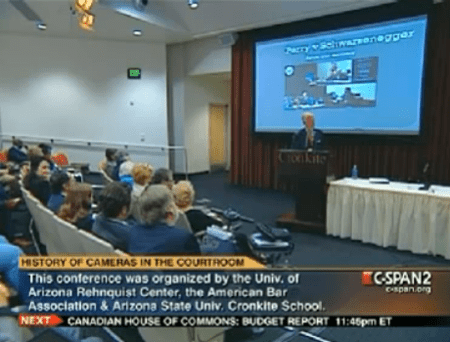

Over the last several months, I have on about a half-dozen occasions given a lecture or talk on the subject of cameras in the courtroom. These presentations included slides and videos from actual trials and re-enactments of trials. These included the Scopes, Hauptmann, Estes, Simpson and Perry trials. The basic point of the presentations is that videos or films of actual trials are more interesting, informative, compelling and, of course, realistic than re-enactments or fictionalized accounts in portraying trial proceedings.

In preparing to leave the district court earlier this year, I began collecting judicial and personal papers. Most of these now are in digital format, so I asked the head of the court's automation unit to download these to an external disk drive. Because the videos of the Perry trial were used in connection with preparing the findings in that case, the videos were included in the judicial papers downloaded to the disk drive.

The rest of Walker's response, including a video clip of his presentation at the University of Arizona in February in which he plays clips from the Perry trial, is AFTER THE JUMP.

In the first several cameras in the courtroom lectures, I used a re-enactment of cross-examination from Perry. When given the disk containing the Perry videos as part of my judicial papers, I decided that in the presentation on February 18 at the University of Arizona it would be permissible and appropriate to use the actual cross-examination excerpt from Perry, instead of the re-enactment. I also used that same excerpt in a talk to a meeting of the Federal Bar Association in Riverside, California on March 8 and in a class I am teaching at the University of California Berkeley School of Law. I am scheduled to give a similar talk at Gonzaga University Law School next week. The Perry excerpt is three minutes in length.

I should also note that the video of the entire Perry trial was made available to the parties in that case and portions were used in the closing arguments in the district court and made part of the record before the case went to appeal. If the court believes that my possession of the videos as part of my judicial papers is inappropriate, I shall, of course, abide by that or any other directive the court makes.

The Perry case involved a public trial. As Chief Justice Berger observed some years ago, "People in an open society do not demand infallibilty in their instructions, but it is difficult for them to accept what they are prohibited from observing.