The Supreme Court has spoken. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is constitutional. As the President said when he repealed "Don't Ask, Don't Tell," "this is done."

Over the next few days, I will unpack this decision. Today, I will summarize the decision and analyze the rationales as briefly as possible. Tomorrow, I will speak about two perspectives on this decision that are important for the LGBT community: (1) What this decision means for Americans with HIV, and (2) What this decision means for the Court's (likely) upcoming consideration of the Defense of Marriage Act.

The Court faced two major issues:

The Court faced two major issues:

1. Does the Constitution allow Congress to require some people to buy health insurance or pay a penalty?

2. Does the Constitution allow Congress to force the states to expand Medicaid in accordance with the ACA's new requirements or lose all their federal Medicaid funding?

It also faced the question of whether it had jurisdiction to hear the case in the first place, given a century's-old law called the Anti-Injunction Act. That law prohibits challenges to a new tax before the tax is actually levied. The Court dismissed this jurisdictional objection, but given how the case turned out (see below), the Court's rationale was fascinating. I will touch on this very briefly.

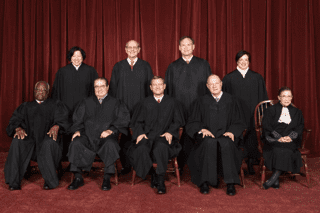

As to the only issues before the Court, the majority found that the ACA's central pillar — buy insurance or pay a penalty — is constitutional. The Court also found that Congress overstepped its authority when it threatened to rescind all Medicaid funding to those states that refuse to implement the ACA's expansion of the program, turning that part of the ACA into an optional system. The vote on the first holding was 5-4 (Chief Justice Roberts joined Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan in the majority, with Justices Kennedy, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito in the minority). The vote on the Medicaid question was 7-2 (Chief Justice Roberts, along with Justices Breyer and Kagan, joined the conservatives).

There are a few lessons to take away from this decision. First, this was a victory for President Obama, the Democratic Party, and for the expansion of the health care, but it may not be a victory for the expansion of federal power. Second, while it is fun to speculate about the Chief Justice's motives for joining the moderate wing of the Court to uphold the ACA — Was he concerned about his legacy? Did he not want to be the man who took us back to the Lochner Era? Was he concerned about the legitimacy of the Court after Bush v. Gore and Citizens United? — such speculation is baseless without inside information, which may not come out for decades. It may indeed be the case that the Chief Justice actually believes what he wrote! Third, the decision reminds us of the incredible power one Justice's vote (and one President's nominee) can have on the political arena and the general welfare.

AFTER THE JUMP, let's dive into the substance of Chief Justice Roberts's and Justice Ginsburg's decisions.

Summary:

I can imagine the first few pages of the Chief Justice's opinion being copied by every high school civics teacher; the decision reads like a mini legal history class about the creation of the Constitution, the structure of Congressional power, and the limited reach of the federal government. The basic point is that this case exists because Congress must base all its actions on a specific grant of power in Article I of the Constitution. If a particular law or Congressional action cannot be justified by an enumerated power, then the law fails. Notably, this is not true of the States. States can tell their citizens to buy health insurance because states have what lawyers call the "police power," or a general grant of power to pass laws to protect the welfare of their citizens. The federal government lacks the police power; instead, our federal system created a more limited reach for Congress and the President.

That reach, however, was never meant to be anemic, and the Chief Justice and Justice Ginsburg remind us of that today.

So, the Government had to justify the ACA on a particular enumerated power. First it tried the Commerce Clause (Article I, Section 8, clause 3), which allows Congress to "regulate interstate commerce," or commercial activity between the States. Alternatively, the Government tried the Necessary and Proper Clause (Art. I, Sec. 8, cl. 18), which is kind of a catch-all that allows Congress to pass laws it deems necessary to fulfill its obligations. Third, the Government argued that the ACA was constitutional under the Taxing Clause (Art I, Sec. 8, cl. 1), which gives Congress the power to "lay and collect taxes." Justices Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan would have found the ACA constitutional under the Commerce Clause. Chief Justice Roberts disagreed, but rescued the law as a lawful exaction under Congress's power to lay and collect taxes. At One First Street (the Supreme Court's address), that different rationale matters; on Main Street, it still means the law survives: you only need one enumerated power to justify a law.

Commerce Clause: The Government argued that because insurance companies can no longer discriminate and have to charge most people the same price for the same plan, the only way the industry could survive was by forcing healthy people into the insurance market. Congress can pass that mandate because the failure to purchase insurance has a "substantial and deleterious effect on interstate commerce" (Nat'l Fed. of Ind. Bus. v. Sebelius, slip. op., at 17 (Robert, C.J.)). Indeed it does, the Government argued. If you only buy insurance when you're sick or if only the sick buy insurance, insurance companies could either not sustain affordable plans or would drop out of business entirely. And, even without the ACA reforms, the decision to not buy insurance shifts costs to those who do, driving up costs of both health insurance for the insured and health care for everyone.

But, although Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce may be broad, it's not unlimited; it, at a minimum, requires that some commerce already exist: "Congress's power to regulate commerce presupposes the existence of the commercial activity to be regulated," and here, there was no such activity (18). By ordering the uninsured to become insured, the mandate creates activity, compelling some of those who had been inactive to become active. To illustrate the point, he analogizes to buying a car: Between the time you buy your first car and your second car, you can hardly be said to be "active in the market" for cars. To see it any other way would be to place absolutely no limits on what Congress could tell us to do. The Government's inability to articulate a so-called "limiting principle" doomed the Commerce Clause argument.

Wickard, the Chief Justice said, was different. Congress could stop the wheat farmer from growing wheat because he was already actively engaged in the production of wheat. Uninsured Americans are not active in the business of producing health insurance.

That is indeed curious. By avoiding the traditional insurance market, I am still choosing alternate insurance, that is, my income, my savings, the equity in my house, my generous family members, all of which could be seen as "insuring" me against costs associated with medical care. And, even if you think that argument is too cute by half, the uninsured are still active in the insurance market by the increases in costs they shift to the insured.

Necessary and Proper Clause: In any event, the Chief Justice disagreed with Government on the Commerce Clause argument. As it did with the alternative Necessary and Proper Clause justification. The Government argued that the mandate was an essential part of a comprehensive legislative scheme of economic regulation (27). But, Chief Justice Roberts rejected this because his reading of Court precedent said that this Clause was not an independent source of power, but rather a way to expand Congressional reach justified somewhere else.

Taxing Power: The Chief Justice found that independent justification in the Taxing Clause.

The individual mandate imposed a tax on those who did not buy health insurance (31). The President may have gone to great lengths not to call it a tax, but the particular labels politicians afix to certain things has very little relevance for the Constitutionality of the resulting legislative enactment. The ACA tells us to buy health insurance, and if we do not buy health insurance, our taxes will go up to some degree. That "penalty" is collected by the IRS, so since the word "penalty" normally describes some punishment for breaking the law, the payment to the IRS for choosing not to buy insurance seems much more like a tax. That is the legalese version of the old adage of inductive reasoning: "If it looks like a tax, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it's probably a duck."

Congress has the power to influence our behavior through taxation (37) and it can regulate inactivity with a tax (41). Nothing in the Constitution prevents either.

So, he concluded as follows:

The Federal Government does not have the power to order people to buy health insurance. [The mandate] would therefore be unconstitutional if read as a command. The Federal Government does have the power to impose a tax on those without health insurance. [The mandate) is therefore constitutional, because it can reasonably be read as a tax.

Medicaid Expansion: The ACA expands Medicaid eligibility to include all those with income up to 133% of the poverty level. It also changes quite a few other things about Medicaid reimbursements, who else can join the Medicaid program, and so on. Congress sought to ensure expanded coverage by telling States, who receive a big block of federal money and then administer Medicaid, that if they don't follow the new eligibility rules, they lose all their Medicaid funding, not just the additional moneys that came with the ACA. And, although Congress has the power to attach conditions to federal money, it cannot coerce the states into doing the federal government's job. The Chief Justice saw the Medicaid section of the ACA as an entirely new program, not an expansion of the old Medicaid, and threatening to deny all funds seemed like a rather blunt object where a sharp blade would have been both more appropriate and constitutional.

Essentially, then, the Chief Justice (along with the conservatives and two liberals) turned the Medicaid expansion section into an optional provision of the ACA.

Justice Ginsburg would have upheld the ACA as a lawful use of Congress's power to regulate interstate commerce. She also would have upheld the Medicaid expansion as written, but only got one other vote on the latter point. Justice Ginsburg's opinion is noted for its traditional (since the 1930s) commerce clause analysis: Congress has the power to regulate activity that substantially affects interstate commerce and courts should give great deference to Congressional determinations of the activity and effects (15). This lowest form of rational basis review was the New Deal Court's revolution and Justice Ginsburg did not want to see it tossed to the side.

She agreed with the Government's central reasoning: the refusal to buy insurance and ultimately consume health care drives up market prices, shifts costs, and reduces efficiency. That is a substantial enough effect on interstate commerce. She challenged the Chief Justice directly: It is Congress that defines the boundary of the market, not the Court, and Congress can regulate activity today based on future events. That, after all, was what Wickard was about. And, the health insurance market is nothing like the automobile market: hospitals have to provide care in emergency rooms, no one has to provide cars (21). Plus, there is a clear limiting principle. The commerce power is limited by case law (27) and by logic. And, both demolish the Chief Justice's concern about a Congress mandating the purchase of broccoli.

Justice Ginsburg responds:

Consider the chain of inferences the Court would have to accept to conclude that a vegetable-purchase mandate was likely to have a substantial effect on the health-care costs borne by lithe Americans. The Court would have to believe that individuals forced to buy vegetables would then eat them (instead of throwing or giving them away), would prepare the vegetables in a healthy way (steamed or raw, not deep-fried), would cut back on unhealthy foods, and would not allow other factors (such as lack of exercise or little sleep) to trump the improved diet. Such “pil[ing of] inference upon inference” is just what the Court refused to do in [its previous cases] (29).

She also takes issue with the Chief Justice's analysis of the Medicaid expansion issue. At its heart, the majority's argument is that threatening to take away all Medicaid funding is coercive and overbroad. But, as Justice Ginsburg states, that is the not the fulcrum upon which the Court has decided its Spending Clause cases. Coercion is saying that there is a federally mandated minimum drinking age and then, if the States do not comply, withhoding a portion of federal highway dollars to those States (South Dakota v. Dole) (Ginsburg, J., concurring, in part, dissenting, in part, at 47). The problem in that case was not that the particular condition placed on federal money was draconian; rather, it is that highway money had nothing to do with a federal drinking age.

Analysis:

This decision is a vindication for President Obama. The ACA was a signature legislative achievement of his first term and now, the Court has affirmed his efforts with this holding:

The Affordable Care Act's requirement that certain individuals pay a financial penalty for not obtaining health insurance may be reasonably characterized as a tax. Because the constitution permits such a tax, it is not our role to forbid it, or to pass upon its wisdom or fairness (Roberts, C.J., at 44).

This holding also resurrects the legal canon that a judge's job is to uphold Congressional legislation if he could. If we could not justify the ACA under the Commerce Clause or the Necessary and Proper Clause, but can justify it under the Taxing Clause, then the ACA is still a lawful exercise of one of Congress's enumerated powers.

Perhaps the Chief Justice was worried that his Court was on the brink of losing the respect of about half the population. Bush v. Gore was 12 years ago but very much on our minds; it feels like Ciizens United was just yesterday; another decision hostile to the American left would have been a third strike that could have made the Supreme Court a focal point of the President's re-election campaign. Perhaps the Chief Justice did not want to be remembered for returning jurisprudence to the 1920s. Then again, maybe he really believes in the law he wrote in his opinion.

Whatever his motives, the Chief Justice was the "swing vote" for the ACA. And, that is a good thing. For too long, this has been Justice Kennedy's court, filling the swing vote role that Justice O'Connor filled before him and that Justice Powell filled before her. It is refreshing to see someone else see the importance of building bridges between the polarized wings of the Court.

The Chief Justice's refusal to be the fifth vote for a Commerce Clause holding may have implications for Congres's power to enact social welfare legislation. The Court had already invalidated parts of the Violence Against Women Act (Morrison (2000)) and the Gun Free School Zones Act (Lopez), holding that a civil remedy to victims of gender-based violence and a ban on guns near schools had no relation to interstate commerce. This case offers us another example of federal social policy that could not be justified under the Commerce Clause, even though the post-New Deal conventional wisdom was that this power was quite expansive. Congress's power in this area is smaller than it used to be; there can be little doubt about that. Yet, Congress's power under the Taxing Clause may now be broader than previously thought. Only time will tell what this means for future social legislation.

The 5-4 vote, and the alternative holding that won the day, also proves the essential role one justice can play and the importance of electing presidents and senators that share our values on important issues facing our nation today. As we will discuss in the coming days, this may have implications for the Supreme Court's eventual consideration of the Defense of Marriage Act, marriage recognition for the gay community, and other social policies.

***

Ari Ezra Waldman teaches at Brooklyn Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. His research focuses on technology, privacy, speech, and gay rights. Ari will be writing weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.

Follow Ari on Twitter at @ariezrawaldman.