Let's pick up where we left off. So far, we've learned that some of the justices expressed concern about jurisdiction to hear Windsor. But, Professor Jackson's argument did not fare well at the Court, though, either. Several justices were likely moved the fact that the federal government is still on the hook for Edie Windsor's $350,000 claim. The mere fact that the Administration's tactics of first defending, then opposing, then winning, and still appealing is unprecedented, does not necessarily make it improper. The Administration's obligations to Ms. Windsor gave it the power to appeal to a higher court, so the Court has jurisdiction to hear the case no matter what. The standing of House Republicans to be the ones to defend DOMA becomes less important, in that case.

Let's pick up where we left off. So far, we've learned that some of the justices expressed concern about jurisdiction to hear Windsor. But, Professor Jackson's argument did not fare well at the Court, though, either. Several justices were likely moved the fact that the federal government is still on the hook for Edie Windsor's $350,000 claim. The mere fact that the Administration's tactics of first defending, then opposing, then winning, and still appealing is unprecedented, does not necessarily make it improper. The Administration's obligations to Ms. Windsor gave it the power to appeal to a higher court, so the Court has jurisdiction to hear the case no matter what. The standing of House Republicans to be the ones to defend DOMA becomes less important, in that case.

We learned that whether the House has standing seemed less of a concern for the Court than whether the procedure the Administration used to get the case got to the Court was proper. It is for this reason, taking it all with a healthy dose of salt, that I think the Court will find it has jurisdiction to hear the case.

AFTER THE JUMP, let's proceed to the substantive portion of the argument, where Paul Clement showed his true colors as an abettor of discrimination and the Court gave us every reason to think it finds DOMA unconstitutional. The question now is the rationale: Will we get a federalism/states' rights decision that would give us a victory, but come back to bite us the next time we're trying to defend a federal civil rights law we like? Or, will we get an equal protection holding that will advance the cause of gay rights in the courts for generations to come? I don't think we can answer this from the questioning alone, but we can tentatively conclude that:

-

Federalism played an important role in the justices' questioning, but not to the exclusion of equal protection. Look for a decision to be informed by both.

-

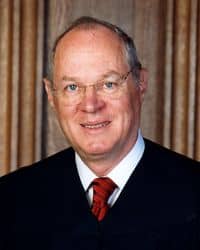

When it comes to Justice Kennedy, he showed consistent skepticism on federalism grounds.

-

The Chief Justice's toughest questions to the anti-DOMA attorneys involved a somewhat related hypothetical, suggesting that the Chief was scraping the bottom of the barrel to find a pro-DOMA argument.

CONTINUED, AFTER THE JUMP…

The Court showed lots of skepticism about the federal government's power to define "marriage." We saw special focus on federalism issues, but also equal protection.

Nothing that happened from here on has challenged my view that the Court will strike down DOMA. Still, it's worth noting that the Court balanced its questions, showing concern for federalism as well as equality.

Taking in all his questions, Justice Kennedy seemed more curious about DOMA's federalism problem. For example, he pounced on Paul Clement's comment that the federal government is involved in marriage in a whole host of areas. Kennedy said that DOMA is different because it may intrude on the states' prerogative to define marriage, not use it as a trigger in a given law. This is a key point. Conservatives like to say that the federal government has had its hands in marriage law for a long time, so DOMA is no different.

Taking in all his questions, Justice Kennedy seemed more curious about DOMA's federalism problem. For example, he pounced on Paul Clement's comment that the federal government is involved in marriage in a whole host of areas. Kennedy said that DOMA is different because it may intrude on the states' prerogative to define marriage, not use it as a trigger in a given law. This is a key point. Conservatives like to say that the federal government has had its hands in marriage law for a long time, so DOMA is no different.

In fact, as Justice Kennedy pointed out early in Mr. Clement's argument, there is a big difference between using the word marriage as a hook when it comes to a given law or a given benefits and a priori defining what is and what will not be a marriage. There are other example, of course, but don't let this hide the fact that Justice Kennedy has issued two gay rights decisions where due process and equality were at the core. His questions on federalism do not mean he thinks DOMA is ok on due process or equal protection grounds; he is just particularly concerned about the federalism problem.

Shortly after came a question from Justice Alito — what is the purpose of something like federal favorable tax treatment for married couples: is it to foster traditional marriage or to focus on support households that function as a single economic unit? — that may be that rare instance where a question can tell us where the Court is going. The conservative Alito was expressing the point we have discussed before that DOMA cannot be about encouraging heterosexuals to marry because it deals with the benefits given after two people decide to get married. Those benefits are about a married couple functioning together, not about the sex or sexual orientation of those married. This is a conservative justice criticizing the marriage rationale for DOMA. I think we saw evidence of DOMA's downfall here.

Shortly after came a question from Justice Alito — what is the purpose of something like federal favorable tax treatment for married couples: is it to foster traditional marriage or to focus on support households that function as a single economic unit? — that may be that rare instance where a question can tell us where the Court is going. The conservative Alito was expressing the point we have discussed before that DOMA cannot be about encouraging heterosexuals to marry because it deals with the benefits given after two people decide to get married. Those benefits are about a married couple functioning together, not about the sex or sexual orientation of those married. This is a conservative justice criticizing the marriage rationale for DOMA. I think we saw evidence of DOMA's downfall here.

It was Mr. Clement's response to Justice Alito's question that was perhaps the most remarkably ironic and illogical statement of the entire argument: DOMA is constitutional because Congress has an interest in treating all gay couples equally. Without DOMA, Mr. Clement said, gay couples in marriage equality states would get federal benefits, but gay couples in marriage discrimination states would not.

I was floored when I heard that, and I imagined that Mr. Clement's head would cartoonishly explode after such nonsense. He argues that precisely because some states ban gays from marrying, a gay couple in one state would get federal benefits and a gay couple in another state would not get benefits if we got rid of DOMA. That means that the government has an interest in treating all gay couples the same, but different (and worse) than heterosexual couples. But, if the government has an interest in treating all couples the same across state lines, shouldn't it also then stop defining marriage and give benefits to all those couples the states say are married? Mr. Clement's logic only holds if you append an explanation for gay couples somehow being less worthy than heterosexual couples. (Read this for yourself at pages 61-67 of the transcript).

What followed was a pretty remarkable 10 minutes that can charitably be described as target practice from all sides. Justice Kagan reminded Mr. Clement that some members of Congress had improper, discriminatory motives for passing DOMA. Justice Kennedy said the entire law didn't make sense, with Section 2 purporting to support states' rights and Section 3 (at issue in this case) taking states' rights away. What Justice Kennedy missed was the implication of juxtaposing Sections 2 and 3: the gratuitous recitation of current law in Section 2 (one state does not have to recognize gay marriages in another state if they violate public policy), coupled with the anti-gay federal definition of marriage in Section 3, proves that Congress didn't really care about states' rights; if it really cared about states' rights, it would have never passed Section 3. Rather, it cared only about discriminating against gays, hence the inconsistency on states' rights. Justice Ginsburg highlighted the multitude of ways that DOMA turns valid gay marriages into "skim-milk" marriages, implying that the only reason someone could support DOMA is if he or she felt diluting gay marriages was somehow a good thing. Mr. Clement struggled to respond, returning often to his talking points about how the federal government always meddles in marriage.

What followed was a pretty remarkable 10 minutes that can charitably be described as target practice from all sides. Justice Kagan reminded Mr. Clement that some members of Congress had improper, discriminatory motives for passing DOMA. Justice Kennedy said the entire law didn't make sense, with Section 2 purporting to support states' rights and Section 3 (at issue in this case) taking states' rights away. What Justice Kennedy missed was the implication of juxtaposing Sections 2 and 3: the gratuitous recitation of current law in Section 2 (one state does not have to recognize gay marriages in another state if they violate public policy), coupled with the anti-gay federal definition of marriage in Section 3, proves that Congress didn't really care about states' rights; if it really cared about states' rights, it would have never passed Section 3. Rather, it cared only about discriminating against gays, hence the inconsistency on states' rights. Justice Ginsburg highlighted the multitude of ways that DOMA turns valid gay marriages into "skim-milk" marriages, implying that the only reason someone could support DOMA is if he or she felt diluting gay marriages was somehow a good thing. Mr. Clement struggled to respond, returning often to his talking points about how the federal government always meddles in marriage.

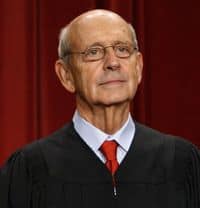

Justice Breyer then pointed out that Mr. Clement conceded that uniformity of law alone could not justify DOMA (setting aside the fact that DOMA does not make the law uniform in any respect), and that we should look at Congress's rational reasons for passing DOMA. Unfortunately, as Justice Breyer points out, Mr. Clement couldn't offer those rational reasons. Breyer also hit him on the argument that the Court should just stay out of the issue as the states debate marriage themselves. Breyer noted that courts step on challenges regarding discrimination on the basis of age in marriage, for example, as evidence that there is no reason why Congress should have to leave this particular marriage issue — gays marrying — up to the political winds without courts getting involved. No effective response from Mr. Clement other than to say gays marrying is something special, code for "redefining traditional marriage."

Justice Breyer then pointed out that Mr. Clement conceded that uniformity of law alone could not justify DOMA (setting aside the fact that DOMA does not make the law uniform in any respect), and that we should look at Congress's rational reasons for passing DOMA. Unfortunately, as Justice Breyer points out, Mr. Clement couldn't offer those rational reasons. Breyer also hit him on the argument that the Court should just stay out of the issue as the states debate marriage themselves. Breyer noted that courts step on challenges regarding discrimination on the basis of age in marriage, for example, as evidence that there is no reason why Congress should have to leave this particular marriage issue — gays marrying — up to the political winds without courts getting involved. No effective response from Mr. Clement other than to say gays marrying is something special, code for "redefining traditional marriage."

The questions to Solicitor-General Don Verrilli and Roberta Kaplan, of Paul Weiss, showed that there are few reasons to keep DOMA.

Chief Justice Roberts took very little time to interrupt Solicitor Verrilli's sad story about discrimination to ask a substantive question about government power: Could the federal government go the other way and define marriage under federal law to include "committed same-sex couples as well." (Side note: If you ever find yourself arguing before a judge, please do not rely on pulling his or her heart strings; focus on the law.). This is an interesting question, but a complete red herring. That intrusion would be very much like DOMA — defining for the states who is married for federal purposes — but the legal issue in Windsor is that the federal government cannot ignore who the states say is married: if a state says two gays are married, they should be married for federal purposes; if they're not married, they're not married for federal purposes. I see no reason to jump to the other side of the coin as the Chief did in his hypothetical.

Chief Justice Roberts took very little time to interrupt Solicitor Verrilli's sad story about discrimination to ask a substantive question about government power: Could the federal government go the other way and define marriage under federal law to include "committed same-sex couples as well." (Side note: If you ever find yourself arguing before a judge, please do not rely on pulling his or her heart strings; focus on the law.). This is an interesting question, but a complete red herring. That intrusion would be very much like DOMA — defining for the states who is married for federal purposes — but the legal issue in Windsor is that the federal government cannot ignore who the states say is married: if a state says two gays are married, they should be married for federal purposes; if they're not married, they're not married for federal purposes. I see no reason to jump to the other side of the coin as the Chief did in his hypothetical.

Justice Kennedy followed up with a federalism question, but as representative of the federal government, Mr. Verrilli never wants to be in a position of arguing that his client has no, or little, power. Mr. Verrilli's evasion on the federalism questions is good representation of his client, nothing more. Besides, we want this case decided on equal protection grounds, not federalism. And, so that is what Mr. Verrilli did for most of his 15 minutes: Like I argued here, DOMA fails because it treats similarly situated couples differently and for no good reason other than disapproval of gays. Mr. Verrilli spoke at length about historical discrimination against gays and the importance of heightened scrutiny given the unique burdens placed on gay persons. Naturally, his argument was challenged by Justices Scalia and Alito. The argument received helpful and supportive questioning from Justice Sotomayor.

When the seasoned Paul Weiss litigator Roberta Kaplan took her turn to speak, she too tried to steer her conversation with the justices back to equal protection and away from federalism. At first, after a softball question from Justice Breyer (who always asks long questions), the Chief Justice was having none of it, asking questions about federalism again. But, Ms. Kaplan is a little too smart for that, focusing on the inequality that DOMA creates. Her answer let Justice Scalia harp on the supposed requirement that gays be "politically powerless" to win heightened scrutiny. I think Ms. Kaplan was doing this purposely, egging on the excitable Scalia to move the front line onto her turf — namely, equality and equal protection. Justice Scalia's crass question doubting that gays have "won the culture wars" allowed Ms. Kaplan to list all the myriad ways in which gays have been and are discriminated against, thus putting DOMA's discrimination in a deeper context, a pattern of behavior of keeping gays down. A powerful strategy indeed, if my intuition is correct.

When the seasoned Paul Weiss litigator Roberta Kaplan took her turn to speak, she too tried to steer her conversation with the justices back to equal protection and away from federalism. At first, after a softball question from Justice Breyer (who always asks long questions), the Chief Justice was having none of it, asking questions about federalism again. But, Ms. Kaplan is a little too smart for that, focusing on the inequality that DOMA creates. Her answer let Justice Scalia harp on the supposed requirement that gays be "politically powerless" to win heightened scrutiny. I think Ms. Kaplan was doing this purposely, egging on the excitable Scalia to move the front line onto her turf — namely, equality and equal protection. Justice Scalia's crass question doubting that gays have "won the culture wars" allowed Ms. Kaplan to list all the myriad ways in which gays have been and are discriminated against, thus putting DOMA's discrimination in a deeper context, a pattern of behavior of keeping gays down. A powerful strategy indeed, if my intuition is correct.

Paul Clement's rebuttal ended the same way Charles Cooper's rebuttal ended yesterday: gay marriage is going to win through the political process; the Court should stay out of it. I'm happy to have Mr. Clement on board with the eventual equality of my love, but his callous insistence on not only waiting, but also leaving our rights up to the good graces of others does violence to the Constitution and this country's traditions of equality and liberty. It's very convenient now for anti-equality judges and attorneys to note that politicians are "falling all over themselves," as the Chief Justice said to Ms. Kaplan, to be on our side; it makes them seem less hateful. But, it abdicates the judiciary's responsibilities. The Framers created three co-equal branches of government, not one that is always supposed to defer to whatever one of the other branches says. Courts have to step in when majoritarian tyranny and ignorance and hate take a knife to democratic principles. Doing anything less is worse than just asking minorities to patient for the haters to come around; rather, it eviscerates all principles of justice upon which democratic systems are based.

This Court looks primed to eviscerate DOMA instead.

If you missed Part 1 of the DOMA SCOTUS arguments analysis, Find it HERE.

***

Ari Ezra Waldman teaches at Brooklyn Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. His research focuses on technology, privacy, speech, and gay rights. Ari will be writing weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues. You can follow him on Twitter at @ariezrawaldman.