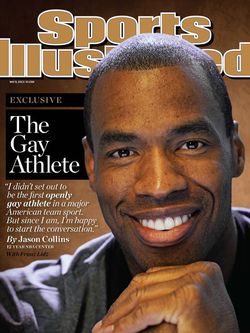

Yesterday, Jason Collins walked out of the closet, beaming and proud. All smiles in his cover photo on Sports Illustrated and alternating between jocular and serious during his interview with George Stephanopoulos on Good Morning America, Jason oozed the relaxed happiness that many of us who have come out feel right after we speak those first three words: "I am gay."

That Jason is a gay, black NBA star is important to a lot of people: to young gay athletes, to gay black men, to the entire gay community. Martina Navratilova was correct when she said that Jason's coming out "will save lives." Andrew Sullivan was correct when he said that Jason has "single-handedly increased the level of oxygen gay athletes can breathe." Frank Bruni took a more nuanced, longer view, noting that Jason is rightfully getting so much attention because the discriminatory world in which we live makes being gay a big deal, even though most of us would much rather not have to lead with our personal lives.

That Jason is a gay, black NBA star is important to a lot of people: to young gay athletes, to gay black men, to the entire gay community. Martina Navratilova was correct when she said that Jason's coming out "will save lives." Andrew Sullivan was correct when he said that Jason has "single-handedly increased the level of oxygen gay athletes can breathe." Frank Bruni took a more nuanced, longer view, noting that Jason is rightfully getting so much attention because the discriminatory world in which we live makes being gay a big deal, even though most of us would much rather not have to lead with our personal lives.

The truth is that identity plays a necessary, multi-faceted role in the sometimes difficult march toward full equality. There's a social paradigm called the "contact theory" that suggests that the best way to reduce prejudice between two groups is to increase interpersonal connection. In other words, professional sport needs openly gay athletes because once heterosexual athletes know and respect an openly gay teammate, homophobia will disappear. Similarly, middle America needs everyday gays and lesbians to come out so they can put a real face to what they used to consider an "other" or different or confusing.

But identity plays a greater role than just influencing others, as important as that might be.

As gay persons, we have a political and legal identity thrust upon us by a world in which our identity is the basis for discrimination. Denial of the centrality of that identity perpetuates the legitimacy of the discrimination by belittling its devastating impact.

Jason could have continued on his way, hiding his sexuality, and instead focusing on his intelligence (he went to Stanford), his religion, and his family. But, as he tells it, to do so was to deny the most important thing about him today. In 2030, that the New York Giants may have a gay wide receiver or that the San Francisco Giants have a gay starting pitcher should be the antithesis of newsworthy. But today, Jason's sexuality is the only thing that's news. He has given voice to a gagged minority mightily struggling to be honest while yearning to be judged purely on their contributions on the field. It took a man willing to be the gay athlete so they could just be athletes.

Continued AFTER THE JUMP.

Follow me on Twitter at @ariezrawaldman.

Many people construct their identities on a host of social ties, from their families, religions, genders, socioeconomic status, national heritage, wants, desires, professions and professional goals, and so on. The list is endless. But, for almost everyone, there is usually one — or two or three — of their community ties that are more important than others. For some, however, the most powerful social identity is the one that is subject to hate or discrimination from the outside world. That is, women tend to see themselves more as women voters than men see themselves as men voters, in part because historic discrimination against women forced them to organize together. The same is true for most black voters and Hispanic voters.

For many of us, being gay and subject to discrimination as gay persons defines our political identities. We may not always want it this way, but the challenges we face because others discriminate against us is an identity thrust upon us. Surveys of gay voters show lopsided skews toward liberalism in politics, but when asked how they would feel about this or that economic issue or this or that candidate in a future world where there is zero sexual orientation discrimination, suddenly our community becomes politically diverse.

For many of us, being gay and subject to discrimination as gay persons defines our political identities. We may not always want it this way, but the challenges we face because others discriminate against us is an identity thrust upon us. Surveys of gay voters show lopsided skews toward liberalism in politics, but when asked how they would feel about this or that economic issue or this or that candidate in a future world where there is zero sexual orientation discrimination, suddenly our community becomes politically diverse.

That's the world we want. But it's not the world we have.

In the world we have, coming out as gay is an essential step toward full equality and, therefore, coming out is constitutionally protected as political speech. This is what the Supreme Court and several court federal and state courts have said for years, protecting so-called "coming out speech" from prior restraints and ex post retaliation or punishment. For example, the Court has said that gay students at public universities are free to host and publicize a panel discussion about sexuality and an attendant social event because coming out is political speech: it goes right to the core of a newsworthy issue of the day. Since then, courts have protected student and non-student coming out speech for the same reason.

Jason Collins' coming out is clearly newsworthy. It's newsworthy not because we want it to be, but because it has to be. And this doubles Jason's bravery. It is undoubtedly brave to be the first man to come out as gay in one of America's most popular four sports. We have no idea if he will get another job. We have no idea if he will receive threats. We have no idea if someone is going to attack him verbally or physically in the locker room. We have no idea what is in store for him and his decision to embrace that uncertainty so he could live an honest open life is the definition of maturity and is the kind of character we want to see in our role models.

Jason Collins' coming out is clearly newsworthy. It's newsworthy not because we want it to be, but because it has to be. And this doubles Jason's bravery. It is undoubtedly brave to be the first man to come out as gay in one of America's most popular four sports. We have no idea if he will get another job. We have no idea if he will receive threats. We have no idea if someone is going to attack him verbally or physically in the locker room. We have no idea what is in store for him and his decision to embrace that uncertainty so he could live an honest open life is the definition of maturity and is the kind of character we want to see in our role models.

It is also brave to be willing to make the sacrifices necessary to be the first to come out in any context. Jason will be remembered as the gay athlete even though a cursory look at his stats as a center in the NBA gives us several reasons to remember him. It would be wonderful if phrases like "the gay athlete" or "the gay professor" or "the gay actor" were erased from our lexicon. But until then, we need men and women willing to be the gay. And for that, we thank Jason Collins.

***

Ari Ezra Waldman is the Associate Director of the Institute for Information Law and Policy and a professor at New York Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. Ari writes weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.