The upcoming Supreme Court decisions on DOMA and Prop 8 will not be the last word on marriage, in particular, or gay rights, in general. As we look forward to those words, however, let's take a look ahead and discuss how the legal landscape may be more complicated after the end of June. "Gay Rights After SCOTUS" is Towleroad's series on LGBT legal issues after Perry and Windsor. In today's column, what are the implications if the Court finds no standing in Perry and no jurisdiction in Windsor.

For nearly two years, we have been familiarizing ourselves with some of the basic issues of federal litigation, including the byzantine rules of standing and jurisdiction. Standing is the right to bring a case in the first place; jurisdiction refers to whether a given court can hear a given case. They are two sides of the same coin: both standing and other jurisdictional questions do not touch on the substantive question the case asks, but rather help determine whether a party can bring a case and whether a court can hear it. They serve gate-keeping roles, preventing frivilous lawsuits or proceedings that violate the Constitution.

For nearly two years, we have been familiarizing ourselves with some of the basic issues of federal litigation, including the byzantine rules of standing and jurisdiction. Standing is the right to bring a case in the first place; jurisdiction refers to whether a given court can hear a given case. They are two sides of the same coin: both standing and other jurisdictional questions do not touch on the substantive question the case asks, but rather help determine whether a party can bring a case and whether a court can hear it. They serve gate-keeping roles, preventing frivilous lawsuits or proceedings that violate the Constitution.

And they may give us somewhat unsatisfying results in the DOMA and Prop 8 cases.

What happens if jurisdictional questions get in the way of the Supreme Court's decision on DOMA and the freedom to marry?

The question in the Perry case is whether the citizens who wrote and pushed for Prop 8, the group ProtectMarriage, had the right to appeal Judge Walker's ruling to the Ninth Circuit. If not, Prop 8 is dead and the freedom to marry returns to California. But it returns only to California and the Ninth Circuit's decision is wiped out.

The question in the Windsor case is whether the case is at the Court's doorstep through the proper process and with the proper parties. If the Court finds it had no jurisdiction to hear the DOMA case, we would be left with the absurd rule that DOMA is unconstitutional in some areas and legal in other areas. That would be an administrative and legal nightmare.

On a broader view, jurisdictional decisions in Windsor and Perry would not be cop outs, but they would provide an unsatisfying stop along the way to full equality, most likely extending our journey and making it more difficult by virtually guaranteeing more trips to the Supreme Court. This might not be a bad thing, especially if the alternative is a anti-equality decision. AFTER THE JUMP, let's discuss the questions that jurisdictional holdings will and will not answer.

CONTINUED, AFTER THE JUMP…

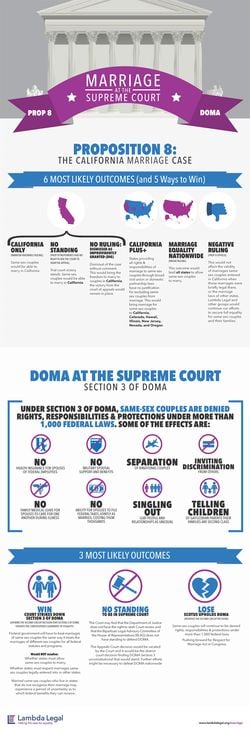

As Lambda Legal's handy infographic explains, there are multiple avenues the Court could take. One path holds that despite all the time and effort we've spent bringing these cases to the Supreme Court, these cases don't belong there. And because the pro-equality side won in the courts below, such decisions would give us a good result. In Prop 8, Judge Walker's decision would stand and the world's fifth largest economy (California) would be the next equality state. In the DOMA case, the Second Circuit decision declaring DOMA unconstitutional would stand and DOMA would be unconstitutional in some jurisdictions. Notably, there are several other DOMA cases — Golinski in California, Gill in Massachusetts, and Pedersen in Connecticut — which could take over the process, but that would take us into the Court's next term.

As Lambda Legal's handy infographic explains, there are multiple avenues the Court could take. One path holds that despite all the time and effort we've spent bringing these cases to the Supreme Court, these cases don't belong there. And because the pro-equality side won in the courts below, such decisions would give us a good result. In Prop 8, Judge Walker's decision would stand and the world's fifth largest economy (California) would be the next equality state. In the DOMA case, the Second Circuit decision declaring DOMA unconstitutional would stand and DOMA would be unconstitutional in some jurisdictions. Notably, there are several other DOMA cases — Golinski in California, Gill in Massachusetts, and Pedersen in Connecticut — which could take over the process, but that would take us into the Court's next term.

Those results would be unsatisfying even though it allows California's gay couples to marry and further damages the DOMA brand.

First, it would wipe out the Ninth Circuit's decision in Perry v. Brown. If you recall, that decision held that Prop 8 was unconstitutional not on the broad grounds that gay marriage bans violate equal protection or due process, but because California could not take away marriage rights already granted. That decision has its own problems, but it was, at a minimum, the first federal appellate court that declared a ban on marriage equality unconstitutional. A standing holding by the Supreme Court would hold that the Perry case should not have been before the Ninth Circuit at all, thus erasing that decision and its precedential value.

Second, it would create an absurd situation where DOMA is unconstitutional in the First and Second Circuits — and possibly soon the Ninth Circuit — and legal everywhere else. Administration of that result would be exceedingly hard: If you lived and married in New York, you get federal benefits and the IRS, immigration authorities, and others would treat you as married. If you lived down the highway in Maryland, you can get married, but since you're in the Fourth Circuit, where DOMA is still viable, you're strangers in the eyes of the federal government.

But a standing decision in the Prop 8 case is likely the best result we can realistically espect. The Court is unlikely to reach a sweeping decision legalizing marriage equality everywhere. The Court is also not likely to adopt the President's so-called 8 State Solution, which would invalidate marriage bans in those 8 states that have civil union laws that are identical to marriage, but without the name. We've discussed the logical problem with that argument before. Plus, I am not confident that this otherwise conservative Court will be able to cobble together 5 votes for anything other than the most narrow decision on an issue that is so toxic to some of them.

And thats ok. If a case is not properly before a court, that court has to dismiss it. Otherwise, we'd be inundated with frivolous and ridiculous lawsuits. It means that our quest for a national right to marry will continue going from state to state and would require another case to reach the Supreme Court (if we choose to go that route again), but it may not be such a bad thing to continue to drive our momentum forward in the states and give the federal courts some time to catch up.

***

Follow me on Twitter: @ariezrawaldman

Ari Ezra Waldman is the Associate Director of the Institute for Information Law and Policy and a professor at New York Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. Ari writes weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.