In South Sudan, politicians have proposed a bill that would criminalize sexual acts between people of the same sex. In Sudan, homosexuality is punishable by death.

In Nigeria, people accused of homosexual acts face 14 years in prison, but in states governed by Sharia (Islamic) law, the maximum penalty is death. Accused homosexuals are publicly whipped in court, and upon leaving the courtroom some must even be protected from crowds.

In Nigeria, people accused of homosexual acts face 14 years in prison, but in states governed by Sharia (Islamic) law, the maximum penalty is death. Accused homosexuals are publicly whipped in court, and upon leaving the courtroom some must even be protected from crowds.

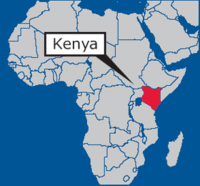

In Kenya, a new constitution that took effect in 2010 guarantees equal protection to all citizens, but it does not explicitly mention homosexuals, leaving room for debate. That same year authorities failed to prosecute individuals who participated in a string of mob beatings in 2010 that left several men hospitalized outside a Mombasa health center.

Legal groups say Kenya's justice system rarely prosecutes homophobic crimes, but that may soon change: In 2011 the incoming President of Kenya's Supreme Court Dr. Willy Mutunga called gay rights the “other frontier of marginalization” in Kenyan society in a signal that he may pressure Kenya's judiciary to decriminalize homosexual acts.

Socially, Kenyans are embracing homosexuality faster than any other African nation. In 2007, a Pew Research Study found only four percent of Kenyans said homosexuality should be accepted. When researchers repeated the survey last year, the percentage of people who accept homosexuality doubled, and in some ways daily life in Nairobi seems to reflect that trend.

An international gay rights organization recently compiled a list of dozens of gay-friendly businesses, organizations and individuals in Kenya.

Next month Kenya will host the second International Conference on African Same-Sex Sexualities and Gender Diversity (the first was held in 2011 in South Africa—by far the continent's most gay-friendly country).

Acceptance of homosexuality in Kenya varies greatly by region, tribe, gender and religion. Among the Luo tribe that inhabits Western Kenya, for instance, “a man who associates with women (but) not in a sexual way is even allowed to wear women's clothes” and adopt a somewhat female lifestyle, said Odhiambo, the professor and LGBT book editor.

He added that Kenyans are much more accepting of lesbianism than they are of relationships between men, explaining the derogatory Swahili word for gays “shoga,” meaning “a confidant,” is an entirely normal description used for women who are close friends, but in masculine Kenyan culture it is used to insult men.

“Many Kenyans can't understand the relationship between a man and a man because they reduce it only to sex,” Odhiambo said, adding that Kenyan society tends to view men who remain unmarried into their late 30s or 40s with suspicion.

In media and politics, homosexuality remains taboo

Kenyan scholars and activists disagree about what factors perpetuate anti-homosexual attitudes in Kenya today.

“The source of homophobia is the Church,” said Makokha, the reverend who works with churches and mosques throughout Kenya to promote acceptance of gays. He said he and fellow activists spend most of their time convincing families of LGBT individuals that “Having an LGBT child is not a curse from God.”

“The source of homophobia is the Church,” said Makokha, the reverend who works with churches and mosques throughout Kenya to promote acceptance of gays. He said he and fellow activists spend most of their time convincing families of LGBT individuals that “Having an LGBT child is not a curse from God.”

Makokha said Muslims “are a bit radical when it comes to the dialog on sexuality and faith. The Koran says (homosexuals) should be stoned to death.” But unlike in Nigeria, Kenyan Muslims do not act upon such decrees. Indeed, Makokha said many religious edicts are interpreted less strictly in Kenya than elsewhere in the region.

“If a man should be stoned to death for sleeping with another woman outside marriage, we wouldn't have many men left,” he said.

One of the most vocal opponents of homosexuality in Kenya is Anglican Archbishop Eliud Wabukala, who is also Chairman of a regional African Anglican group that opposes gay marriage. Last week Wabukala published a letter criticizing two prominent Anglican leaders in England for speaking out against anti-gay legislation in Uganda and Nigeria.

One of the most vocal opponents of homosexuality in Kenya is Anglican Archbishop Eliud Wabukala, who is also Chairman of a regional African Anglican group that opposes gay marriage. Last week Wabukala published a letter criticizing two prominent Anglican leaders in England for speaking out against anti-gay legislation in Uganda and Nigeria.

Some gay rights activists see this division in the church as encouraging: Those who identify as LGBT are often well aware of which churches accept homosexuals and can attend in accordance, according to Anne Baraza, who advocates for gay rights with her husband, Makokha. In contrast, “I doubt whether there is a church in Uganda where everyone welcomes the gay community freely,” she said.

Nor does the opposition to homosexuality by the Anglican Church here keep gays themselves from attending Anglican services.

“We've had those discussions with some preachers who preach against it. But that doesn't mean there are no LGBT individuals in the church,” said Peter, a practicing Anglican who is gay and asked to be identified by his first name only because he has not yet come out publicly. “I tend to think (Reverend Wabukala) doesn't like strongly discussing the issues…he does it so carefully, he tries to avoid it as much as possible.”

Even some of the staunchest critics of homosexuality here are more reserved than their peers in the region. Both Wabukala and a Kenyan senator who has publically denounced gays in the past declined an interview with GlobalPost.

Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta has been notably silent on the issue.

Some accuse Kenya's news and entertainment media of failing to discuss homosexuality in an appropriate manner. Popular talk radio programs in Nairobi routinely discuss relationships, but no one interviewed for this article could recall a discussion of homosexual relationships on the airwaves.

One of Kenya's most popular newspapers, the Standard, occasionally prints incendiary articles with headlines such as “They Have ‘Infected' Kenya! Has the Gay Debate Reached Nairobi?” In July, The Standard fabricated facts in an article about a supposed ‘gay lobby' for which no evidence or source was provided.

“Gay people are still in the closet because they (don't) know, ‘after I am featured in the media, what will come next? Will I be kicked out by my landlord?” Baraza said. “A friend texted me the other night to say there is a ‘gay debate' on TV. And she is homophobic. But at least she is watching.”

Kenyan gays wait for the right moment to come out

Kenyan gays wait for the right moment to come out

Gays and gay rights activists here agree that, paradoxically, public opinion over homosexuality will not shift drastically until LGBT individuals feel comfortable speaking openly about their identities.

Peter, the 32-year-old Anglican, says he is not yet ready to reveal himself, even to his own mother.

“I've come out very gradually, and not to everybody. Of course, my mom is very suspicious. Being a strong Christian…she always mentions the ‘issue' of homosexuality,” Peter said. “The Kenyan experience is that many people are still in a place of confusion.”

Peter recalled the chilling experience of being publicly outed and attacked in his Nairobi neighborhood several years ago. He said a neighbor came to his home professing to want to learn more about Peter's activism, but after Peter invited him inside, the man denounced him.

“He said, ‘you are gay and I'm going to tell everybody on this block unless you give me money, because I know you get a lot of money. I'll tell people you tried to rape me,'” Peter recalled. “And he did that.”

Later that evening the man returned with five young men from the neighborhood who dragged Peter from his home and started beating and kicking him, Peter said. He eventually escaped and made it to a hospital for treatment.

“I reported to the police, but my lawyer said I have to be ready, because…‘it will be public that you are gay.' He said I have to be psychologically prepared,” Peter said. “And at that time, because of the very homophobic environment, I thought I would just expose myself too much. So I just dropped the case.”

Peter and other gay rights activists said they're optimistic that a shift in the broader priorities of Kenyan society is improving the environment for LGBT individuals to come out here.

In a nation eager to establish its reputation as an economic power and innovator, many Kenyans see no reason to exclude otherwise productive members of society from the workplace or social sphere on account of their sexual orientation.

For that reason, it is easier for some people to come out “when they are stable in life and they are not depending on anybody,” Peter said. “People who have been outed and they're not stable, we've seen them be rejected. And their families think they must suffer until they come back to the right way. Once you are out, you are not going to be employed by anyone who knows that. You're not going to be given moral support.”

“I do not think it is the right time for me,” Peter said. “If they say, ‘go to hell,' I want to be able to say, ‘that's OK, I will support myself.'”