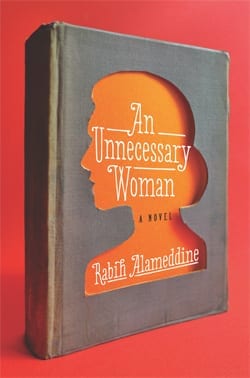

Aaliya Selah, the irreverent, vibrant, hilarious, and fiercely solitary narrator of Rabih Alameddine's brilliant new novel, has practiced a strange, consoling ritual for fifty years. Over the course of twelve months, beginning on January 1st, she translates a book, perfects it, seals it in a box, and places it in the back room of the apartment in Beirut where she has spent her entire adult life. No one reads these pages, including Aaliya herself: “Once the book is done,” she says, “the wonder dissolves and the mystery is solved. It holds little interest after.”

In a world where women's lives revolve around husbands and children, Aaliya has lived alone since her husband divorced her after four failed years of youthful marriage. In her 70s now, estranged from her family, almost friendless, no longer working in the bookshop she tended for years, Aaliya has become the “unnecessary woman” of the title. “I am nothing,” she says at her most despondent; “I'm a wholly nondescript human.”

In a world where women's lives revolve around husbands and children, Aaliya has lived alone since her husband divorced her after four failed years of youthful marriage. In her 70s now, estranged from her family, almost friendless, no longer working in the bookshop she tended for years, Aaliya has become the “unnecessary woman” of the title. “I am nothing,” she says at her most despondent; “I'm a wholly nondescript human.”

But the space of the “unnecessary” is also the space of art, and in the absence of the usual obligations Aaliya has dedicated herself to literature. She fills her days with reading, and she works on her translations in a kind of absolute innocence, free of any taint of commerce or fame. “I'm committed to the process and not the final product,” she says. “It's the act that inspires me, the work itself.”

One of the wonders of this novel is how, from the perspective of such an outwardly circumscribed existence, Alameddine offers a rich, variegated portrait of a community. Though she hardly talks to them, Aaliya participates in the lives of her neighbors, women who gather daily for coffee and conversation, which Aaliya follows from her room. Though she doesn't like to admit it, she weeps with both their sorrows and their joys.

She also, at least from time to time, descends into the streets of Beirut, a city for which she feels a deep and ambivalent love. “Beirut is the Elizabeth Taylor of cities,” Aaliya says, “insane, beautiful, tacky, falling apart, aging, and forever drama laden.” She remembers its many recent traumas, including civil war and Israeli siege, the marks of which are visible in bullet holes and armored stairwells. Her own apartment was broken into by looters, which prompted her to take steps toward her own defense; for years she “slept with an AK-47 instead of a husband.”

But it's a different kind of intruder that disturbs Aaliya's peace in Alameddine's novel. Startled one afternoon by a knock at the door, Aaliya finds her brother's family, with her elderly, senile mother in tow. They insist that it's Aaliya's turn to care for the old woman; Aaliya, her need for independence outweighing her remorse, even horror, at her own cruelty, refuses: “‘No,' I say, in a low, sticky tone. ‘She is not mine.'”

But it's the mother's response that is most shocking. When she sees her daughter and realizes where she is, she screams, “a defiant skirl of terror that does not slow or tire.” This scream will haunt the rest of the book, finally compelling Aaliya to undertake a journey into her past that may also, in unexpected and surprisingly tender ways, be an opening toward her future.

Aaliya constantly expresses her disdain for the tidy endings that mar so many literary texts, the revelations and epiphanies that allow for the kind of resolution that real life almost never achieves. But as the novel progresses it's clear she is approaching her own reckoning, an increasingly desperate sense that, instead of giving meaning to her life, her devotion to literature may have kept her from the work of living.

Aaliya constantly expresses her disdain for the tidy endings that mar so many literary texts, the revelations and epiphanies that allow for the kind of resolution that real life almost never achieves. But as the novel progresses it's clear she is approaching her own reckoning, an increasingly desperate sense that, instead of giving meaning to her life, her devotion to literature may have kept her from the work of living.

“I made myself feel better by reciting jejune statements like ‘Books are the air I breathe,'” she writes, “or, worse, ‘Life is meaningless without literature,' all in a weak attempt to avoid the fact that I found the world inexplicable and impenetrable.” While she has prided herself on being above the myths of politics and religion that have wreaked such havoc in the world, Aaliya comes to feel that she may have made her own false idol of art.

But this won't be Aaliya's final or immutable judgment, and the book bears witness to the uncounterfeitable joy she has taken in literature, a joy I found myself sharing as I read this extraordinary book. Aaliya Saleh's voice is an indelible addition to the literary chorus she so loves, and An Unnecessary Woman is the most remarkable new novel I have read in many months.

Previous reviews…

Edmund White's ‘Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris'

Randall Mann's ‘Straight Razor'

Janette Jenkins' ‘Firefly'

Gengoroh Tagame's ‘The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame'

Garth Greenwell is the author of Mitko, which won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for both the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award and a Lambda Award. His new novel, What Belongs to You, is forthcoming from Faber/FSG in May 2015. He lives in Iowa City, where he is an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. Connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.