Saeed Jones begins this electrifying book—one of the most exciting debut collections I've read in years—with a quotation from Kafka's notebooks: “The man in ecstasy and the man drowning—both throw up their arms.”

It's a powerful opening for these searing poems, in which pleasure and pain are often indistinguishable, and in which desire is almost always inextricable from violence. “I've got more hunger than my body can hold,” Jones writes in “Last Call,” and hunger often drives the speakers of these poems to danger. “Night presses the gunmetal O of its mouth / against my own,” he writes in the same poem; “I can't help how I answer.”

It's a powerful opening for these searing poems, in which pleasure and pain are often indistinguishable, and in which desire is almost always inextricable from violence. “I've got more hunger than my body can hold,” Jones writes in “Last Call,” and hunger often drives the speakers of these poems to danger. “Night presses the gunmetal O of its mouth / against my own,” he writes in the same poem; “I can't help how I answer.”

How to tell apart joy and pain in a book where dancing is “a way / of mapping out hell with my feet,” as Jones writes in “In Nashville,” and looks like “Guernica on all fours” (“Katamine and Company”), where “Even a peacock feather comes to a point” (“Thallium”)?

In “Pretending to Drown,” even one of the book's most tender scenes—two boys go skinny dipping together—holds out the promise of a threat. The speaker sinks under the water to see the other boy “as the lake saw you: cut in half / by the surface, taut legs kicking / the rest of you sky.” It's a game, but also an invitation, and when he comes back up it's accepted: “slick grin, / knowing glance; you pushed me / back under. // I pretended to drown, / then swallowed you whole.”

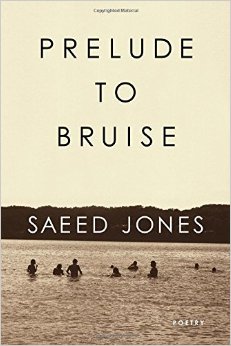

In Prelude to Bruise, Jones takes on at once the most intimate and the most public of themes: desire, family, race, art, America and its romance with violence. But the book's real ambition is to force us to see that any division between public and private is arbitrary, if not fraudulent. It's often said that the personal is political; few books have made me feel it as viscerally as this one.

These poems bear witness to the fact that to be black and gay in America—and especially in the American South—is to be confronted with violence from every side: on the street and in the home; from strangers and friends alike; most painfully, from within the self.

Many of the poems take place in cities—Birmingham, Jasper, New Orleans—that are sites of particular trauma in the history of race in America. In “Lower Ninth,” the speaker observes the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans, still devastated long after Katrina. In “Jasper, 1998,” a haunting poem, Jones takes on the voice of James Byrd, who was dragged to death in Texas by three white supremacists. In the poem's devastating final section, Jones uses the particularly American rhythm of the chain gang to make us feel Byrd's torture:

Chain gang, work song, back road,

my body.

Chain gang, work song, back road,

my body.

The book's protagonist is known only as “Boy,” a name that condenses to a single word many of this collection's difficult themes. It's at once a term of tenderness (“he's still your boy,” the poem “Insomniac” says to a worried mother) and desire (in internet chatrooms every second screen name is a variant of “boy”); it's also a term of race hatred. In the collection's title poem, it's spoken in both desire and hatred at once, when during sex a man tells the speaker, “I like my black boys broke, or broken. / I like to break my black boys in.”

In “History, According to Boy,” the powerful prose narrative that closes the volume, we follow Boy through a childhood landscape scarred by violence, if not quite literally made of it: in a country at constant war, in a city where gay men are murdered behind bars, he lives in a “house made of guns.” Eyes are “narrow as knife wounds”; “a bare lightbulb shines…like a lynched moon.”

In “History, According to Boy,” the powerful prose narrative that closes the volume, we follow Boy through a childhood landscape scarred by violence, if not quite literally made of it: in a country at constant war, in a city where gay men are murdered behind bars, he lives in a “house made of guns.” Eyes are “narrow as knife wounds”; “a bare lightbulb shines…like a lynched moon.”

Boy is an alien both in and out of his home, increasingly as both he and those around him become more aware of what he desires. The violence around him intensifies, until in the final scene he finds himself nearly engulfed by it, on the point of becoming not just a victim but a perpetrator of terrible acts.

Like the great poets his lines recall—Whitman, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, James Baldwin, to name just a few of the voices that inform this book—Jones makes a music that feels adequate to rage and grief on both a personal and a national scale. Prelude to Bruise is more than a promising debut; it's the rare book of poetry that urgently speaks—and will continue to speak, I suspect, for a long time—to the intractable griefs of our present moment.

Previous reviews…

Michael Carroll's ‘Little Reef and Other Stories'

Francine Prose's ‘Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932'

Mark Gevisser's ‘Lost and Found in Johannesburg: A Memoir'

Emma Donoghue's ‘Frog Music'

Garth Greenwell is the author of Mitko, which won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for both the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award and a Lambda Award. His new novel, What Belongs to You, is forthcoming from Faber/FSG in 2015. He lives in Iowa City, where he is an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. Connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.