AFP

Williamsburg (United States) (AFP) – More than four decades after John Hinckley shot Ronald Reagan, the man who was acquitted of the crime on an insanity defense and subsequently hospitalized for 34 years is fully free.

But the one thing he wants most after decades of treatments and years of conditional release still eludes him: a guitarist and songwriter, Hinckley longs to play a live concert.

On June 15, the day he was released from court oversight, Hinckley also learned the Brooklyn venue where he was scheduled to perform had scrapped his set over safety concerns, saying they'd faced “very real and worsening threats.”

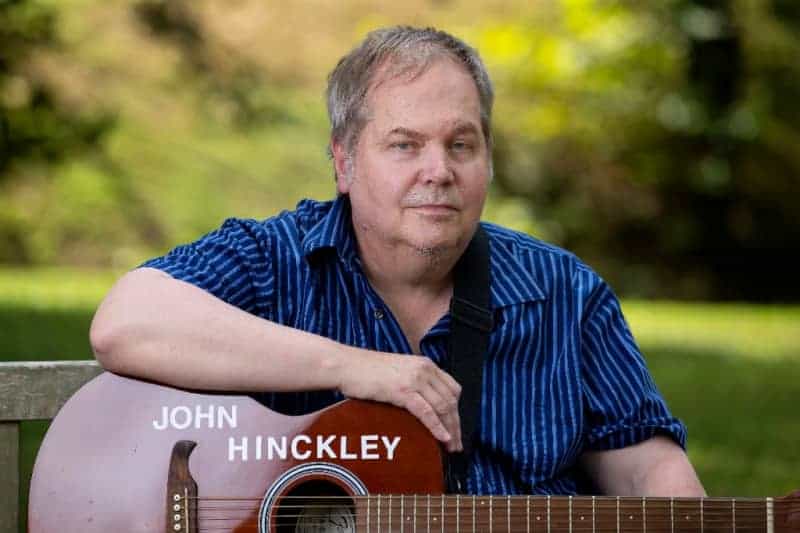

“It was just a huge disappointment,” says Hinckley, who's now 67 and wields an acoustic guitar with his name emblazoned across its soundboard.

He faced the same disappointment just before other scheduled shows in Chicago, Virginia and Connecticut.

Speaking to AFP at a park in Williamsburg, Virginia where he lives in an apartment with his cat Theo, Hinckley insists he's a changed man, eager to share his music with a world that's long branded him “violent and unstable.”

“They know me from all the negativity that came out about me for 41 years, but I'm a different person now,” he says with a southern twang.

Music therapy

On March 30, 1981, Hinckley shot Reagan and three others in Washington. All survived, but the former president's press secretary, James Brady, was left permanently disabled.

Hinckley said he committed the crime to impress Jodie Foster; he'd grown obsessed with the actor after watching her in Martin Scorsese's “Taxi Driver.”

He was declared not guilty on grounds of insanity and admitted to St. Elizabeth's Hospital in Washington for more than three decades.

But Hinckley's public image remained firmly in 1981. Stephen Sondheim wrote him as a character in the musical “Assassins,” while the new wave band Devo released one of his poems as a song.

He was discharged from the hospital in September 2016 but mandated to live with his elderly mother, who has since passed, in Williamsburg. His movements, electronic devices and online activity were limited and monitored.

Those conditions were lifted this summer, and Hinckley passes his days in the sleepy town painting, songwriting and uploading performances online.

He's amassed more than 50,000 Twitter followers, and notches nearly 5,000 monthly listeners on Spotify.

But the self-taught musician yearns for the connection of a live audience.

“I want them to feel better coming out of the show than going into the show,” Hinckley says. “I have people that write to me and say, ‘I listened to your music and it helps me to get through my day.'”

“That's a great feeling.”

‘I'm sorry'

For years, the Reagan Foundation ardently protested Hinckley's freedom, conditional or otherwise, accusing him of seeking “to make a profit from his infamy.”

If his criminal act had not involved someone as high-profile as Reagan, it's likely Hinckley would've been released from the hospital, at least conditionally, earlier than the court approved it.

Even if you are technically acquitted for reasons of insanity, “there is a punitive element to the way the system works,” said Paul Appelbaum, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University.

“If you commit a heinous act — for example, if you try to kill a president of the United States — you can expect to spend a long time confined, whether or not your mental state continues to require it.”

Hinckley holds he has tried apologizing to the Reagan Foundation numerous times.

“I'm sorry for what I did,” he says. “I'm not the person I was back then.”

“I was totally alienated and depressed and unstable” leading up to the attack, Hinckley says.

“I can't relate to the way I was, because now I kind of have that feeling of, ‘What was I thinking?'”

At this point, the barrier to his stage ambitions appears to be a question of morality.

“We're in a society where people have gained fame and notoriety for all kinds of reasons, including not very savory reasons, and in many cases are subsequently able to capitalize on that,” said Appelbaum.

“It's not easy to see why somebody like John Hinckley should be treated differently than everybody else.”

‘Too many guns'

Hinckley offers a folksy brand of acoustic rock with unambiguous lyrics.

“Freedom stands next to me / Everybody knows my history,” he croons on “I Sing My Songs.”

“True remorse is real / It has been the way I feel.”

As his quest for a venue continues, Hinckley's got an album set for release on vinyl by year's end with Asbestos Records, an indie ska and punk label.

He says he's written thousands of songs, with musical influences including Bob Dylan, Neil Young and The Beatles.

Recalling the assassination of John Lennon, which occurred just months before Hinckley's own crime, he says, “I'm sure it didn't help in my psyche to have that happen.”

Hinckley applauded increased attention in recent years to mental health research and treatments, but says he thinks “a lot more can be done.”

“I think the country is in a really, really volatile spot right now,” he says. “I just wish people would calm down.”

And the man who changed his own life forever by wielding a firearm emphasizes a need for gun control.

“There's too many guns in America,” Hinckley reflects, giving his guitar a languid strum.

“That's why all this crime and all this violence keeps happening.”