Kevin Sessums last reviewed Equus and The Seagull for Towleroad. You can also catch up with Kevin online at his own blog at MississippiSissy.com. He also recently wrote a piece on ‘Sperm Washing' for The Daily Beast.

Kevin Sessums last reviewed Equus and The Seagull for Towleroad. You can also catch up with Kevin online at his own blog at MississippiSissy.com. He also recently wrote a piece on ‘Sperm Washing' for The Daily Beast.

Three revivals on Broadway in the last few weeks have pointed up different ways that plays from the recent and distant past can be mounted for audiences in the 21st Century. Each remounting proves the pitfalls and successes of such reimaginings. I'll review the first one today and the next two tomorrow.

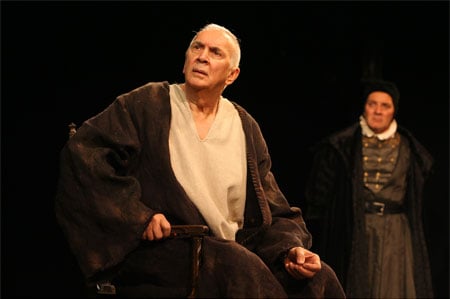

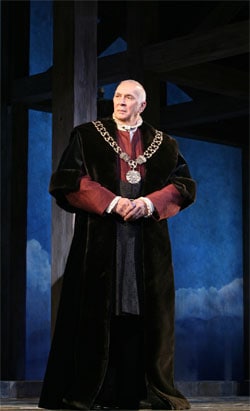

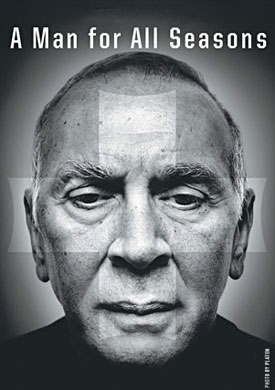

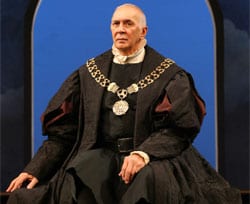

Let's start with the least risky or the three, the Roundabout's museum-like staging of Robert Bolt's A Man for All Seasons, starring Frank Langella. It is a play about Sir Thomas More, the Lord Chancellor of England in 1527, and the battle he engages in with King Henry VIII as well as his own conscience. King Henry had two years earlier begun an affair with Anne Boleyn and therefore to explore the possibility of annuling his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, to whom he had been married for the last 18 years but with whom he had not conceived a male heir.

Let's start with the least risky or the three, the Roundabout's museum-like staging of Robert Bolt's A Man for All Seasons, starring Frank Langella. It is a play about Sir Thomas More, the Lord Chancellor of England in 1527, and the battle he engages in with King Henry VIII as well as his own conscience. King Henry had two years earlier begun an affair with Anne Boleyn and therefore to explore the possibility of annuling his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, to whom he had been married for the last 18 years but with whom he had not conceived a male heir.

Henry is frustrated by the Catholic Church's refusal to grant his request for an annulment and targets the English clergy to submit to his wishes by stoking his country's burgeoning anti-papist sentiments to declare himself the head of a new Church of England. Thomas Cromwell was Henry's henchman in much of his grabs for power during this time, which included going to administrative war with More, who refused overtly to approve of Henry's legal and liturgical machinations until it proved to be his undoing. More ended up imprisoned for never surrendering his conscience to his king and was beheaded for his stubborn belief in his own rightness. Robert Bolt himself was an agnostic and socialist and the play is more about not bending to power than any kind of religious tract.

The first Broadway production of A Man for All Seasons won the Tony for Best Play in 1962 and the film version won the Best Picture Oscar in 1966. Paul Scofield, who originated the role of Sir Thomas More, won both the Tony and Oscar for Best Actor in each of those productions. If any actor could follow in Scofield's footsteps it would be Langella, I guess, though I am in the minority in not being as big a fan of this most self-referential of actors as so many others are. A contemporary of More's, Robert Whittington, a grammarian and Latin scholar, wrote of him, that he was a “man of angel's wit and singular learning … and, as time requireth, a man of marvelous mirth and pastimes and sometimes of sad gravity. A man for all seasons.”

The first Broadway production of A Man for All Seasons won the Tony for Best Play in 1962 and the film version won the Best Picture Oscar in 1966. Paul Scofield, who originated the role of Sir Thomas More, won both the Tony and Oscar for Best Actor in each of those productions. If any actor could follow in Scofield's footsteps it would be Langella, I guess, though I am in the minority in not being as big a fan of this most self-referential of actors as so many others are. A contemporary of More's, Robert Whittington, a grammarian and Latin scholar, wrote of him, that he was a “man of angel's wit and singular learning … and, as time requireth, a man of marvelous mirth and pastimes and sometimes of sad gravity. A man for all seasons.”

Hence, the play's title and much of Langella's performance. Though Langella is quite affecting — and heartbreakingly stirring — in the latter part of the play when he is imprisoned and makes his arguments at court, he is at his plummy best — or is it his worst? — in the first half of the play when he, as More, banters with his family and friends and regal cohorts. I kept thinking that the director Doug Hughes had staged this stodgy production so that nothing could distract from Langella at its center. It was as if I were watching some fustian old Alfred Lunt warhorse of a play that Lunt — Langella is our latter day Lunt, come to think of it — could haul out to tour the hinterlands.

I also kept wondering if it were Langella who had insisted that the Greek Chorus-like part of the Common Man had been cut from this production so as not to steal any of his dramatic thunder. That part was intrinsic to the play's dramaturgy and had originally been played by Leo McKern — yes, he of Rumpole of the Bailey — in London who then took the part of Cromwell in the Broadway production in 1962. The part of the Common Man on Broadway was taken by the late great George Rose.

Allow me a personal aside here.

Continued, AFTER THE JUMP…

During the slowest sections of this production of A Man for All Seasons my mind wandered to dear George, one of the greatest of Broadway's character actors. Some of you Towleroad readers may remember him from the Kevin Kline/Linda Ronstadt Pirates of Penzance production in which he played Major General Stanley or his multiple roles in The Mysteries of Edwin Drood or as Lynn Redgrave's buddy in My Fat Friend or as Alfred Dolittle in the 1976 revival of My Fair Lady. He won Tony Awards for My Fair Lady and Edwin Drood and was nominated for Pirates and My Fat Friend.

During the slowest sections of this production of A Man for All Seasons my mind wandered to dear George, one of the greatest of Broadway's character actors. Some of you Towleroad readers may remember him from the Kevin Kline/Linda Ronstadt Pirates of Penzance production in which he played Major General Stanley or his multiple roles in The Mysteries of Edwin Drood or as Lynn Redgrave's buddy in My Fat Friend or as Alfred Dolittle in the 1976 revival of My Fair Lady. He won Tony Awards for My Fair Lady and Edwin Drood and was nominated for Pirates and My Fat Friend.

Rose was a great friend of Bob Borod, the production stage manager I had when I was in Equus (see my previous review of that revival) and they both took me under their collective wing in the late 1970s. George had been in the production of the Katherine Hepburn musical Coco as well, which was based on the life of Coco Chanel and for which Bob had also been the stage manager. He played Chanel's great friend Louis Greff and received his first Tony nomination for that portrayal. The three of us would all sit up late at Bob's apartment at 40 Fifth Avenue and they would regale me with Hepburn stories and play me tapes of rehearsals that Bob had surreptitiously made when she was learning her musical numbers. George, shocked at how insufferably precocious I had been in sixth grade to attempt to mount my own production of A Man for All Seasons back in Missisippi, would also regale me with stories of the Broadway production and which members of the cast suffered from the severest bouts of flatulence at the play's most dramatic moments.

Once I even volunteered to feed Rose's pet lynx — yes, a pet lynx — he kept in his New York City apartment. It was one of the oddest and scariest things I've ever done in my almost 34 years in NYC and believe me I've done some odd and scary things in this odd and scary city. George had been down at his house in the Dominican Republic. He loved it there so much he even adopted a 14-year-old boy from there since, as an openly gay single man, he had no heir of his own. A few years later his adopted son and the son's real father and uncle beat him to death during one of his visits down there where he is now buried in a non-descript grave in an overgrown cemetery.

Once I even volunteered to feed Rose's pet lynx — yes, a pet lynx — he kept in his New York City apartment. It was one of the oddest and scariest things I've ever done in my almost 34 years in NYC and believe me I've done some odd and scary things in this odd and scary city. George had been down at his house in the Dominican Republic. He loved it there so much he even adopted a 14-year-old boy from there since, as an openly gay single man, he had no heir of his own. A few years later his adopted son and the son's real father and uncle beat him to death during one of his visits down there where he is now buried in a non-descript grave in an overgrown cemetery.

I kept thinking of George Rose and how sardonic he would have been about his role as the Common Man being cut from the Langella production of A Man for All Seasons. He was one of the most uncommon of men himself. He suffered an awful death but his life was a singular one — much like Sir Thomas More — and yes, dear George, I know you're now rolling your eyes as well at that last line.

T T 1/2 (out of 4 possible T's)

A Man for All Seasons, Roundabout Theatre Company at the American Airlines Theatre, 227 West 42 St., New York. Ticket information here.

(images/joan marcus)

Previous Reviews

On the Stage: Equus and The Seagull [tr]