Kevin Sessums recently interviewed Jane Fonda and Moises Kaufman about the new play '33 Variations' for Towleroad, and recently reviewed the plays Becky Sharp and The Third Story. You can also catch up with Kevin online at his own blog at MississippiSissy.com.

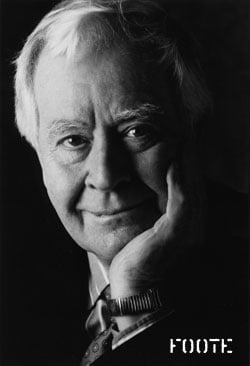

Before I write about three plays I've seen recently, I must sadly pay homage to a couple of theatre greats — first the playwright Horton Foote, who lived a long life and died at 92, and the actress, Natasha Richardson, who lived much too short a life and died this week at age 45.

I didn't get around to reviewing Foote's last play on Broadway before it closed — the divine comedy Dividing the Estate — but it was one of the most pleasurable evenings I spent in the theatre this season. When I was a young man trying to find my way in New York City I got a job being a reader of scripts for a big-time movie company and offering my written critiques of them. As a first assignment I was handed a script titled Tender Mercies by someone I, at that point, had never heard of named Horton Foote.

I didn't get around to reviewing Foote's last play on Broadway before it closed — the divine comedy Dividing the Estate — but it was one of the most pleasurable evenings I spent in the theatre this season. When I was a young man trying to find my way in New York City I got a job being a reader of scripts for a big-time movie company and offering my written critiques of them. As a first assignment I was handed a script titled Tender Mercies by someone I, at that point, had never heard of named Horton Foote.

Much more glib than knowledgeable or wise, I wrote a horridly mean critique of the script, which went on to be made anyway and to win a Best Original Screenplay Oscar for Foote. I've spent all the years since realizing what a boob I was for writing that critique of a man who has been rightly described as the Texas Chekhov. His actress daughter Hallie, who gave one of the season's funniest and fiercest performances in Dividing the Estate, was her father's favorite interpreter. My deeply felt condolences go out to her and the entire Foote family.

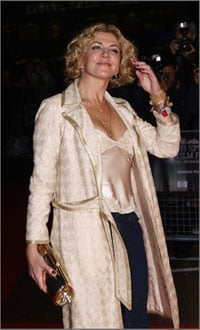

As they do to Natasha's family and friends. I met Natasha several times at parties and baby showers because we shared some of those same friends. You always knew what part of the room she was in because of the sound of her throaty laughter. Always kindhearted and concerned about your well-being, she was instrumental in helping one of my best friends finally kick his cigarette habit when none of us could get him to do it. Yet I was often a bit cowed in her presence — and I am not the cowed type — because of my memories of seeing her onstage as the title character in Eugene O'Neill's Anna Christie opposite her husband, Liam Neeson; as Anna in Closer (the role Julia Roberts played in the Mike Nichols film of the Patrick Marber play); as Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire; and, most thrillingly, as Sally Bowles in Cabaret. I never thought anyone could obliterate the image of Liza Minnelli in the film version of that role, but Natasha certainly did. It was one of the most devastating and heartbreaking performances I've ever seen. I never went back to see other actresses in the part during the musical's long run because I didn't want to sully the memory of her in the role.

She was, as Alexander Woollcott wrote in 1921 of the original production of Anna Christie, "singularly engrossing." As enthralling as she was on the stage, she was even more so off one. Jane Fonda has a lovely remembrance of her as a small girl on the set of Julia in which Fonda co-starred with her mother, Vanessa Redgrave. You can find it on Fonda's blog. And she grew up to be more than just an actress. Because her father, the director Tony Richardson, died of complications from AIDS, she also was a tireless activist and fundraiser regarding HIV/AIDS.

She was, as Alexander Woollcott wrote in 1921 of the original production of Anna Christie, "singularly engrossing." As enthralling as she was on the stage, she was even more so off one. Jane Fonda has a lovely remembrance of her as a small girl on the set of Julia in which Fonda co-starred with her mother, Vanessa Redgrave. You can find it on Fonda's blog. And she grew up to be more than just an actress. Because her father, the director Tony Richardson, died of complications from AIDS, she also was a tireless activist and fundraiser regarding HIV/AIDS.

Again, as Woollcott wrote of Anna Christie: "It came to the chronic playgoers like a swig of strong, black coffee to one who has been sipping pink lemonade." That was what it was like to be in Natasha's presence. She was so invigorating and vibrant and full of life that it is hard to fathom that such a woman has so suddenly been taken from us.

My heart breaks for her children and for her husband and for her whole family, especially her mother, who last appeared on Broadway playing the role of Joan Didion. In that role in the one-woman show based on Didion's book, The Year of Magical Thinking, Redgrave played a grief-stricken woman who has to watch her daughter slip into a coma and then slip away forever. The mind boggles at the Pirandello-like aspect of all of this. But it mustn't all get too theatrical when discussing this most theatrical of families. This is real life. And it is truly tragic.

***OUR TOWN

The most truthful and tragic of all American plays is Our Town. In fact, I consider it the greatest American play of the 20th Century and it is appropriate to be writing about it when discussing the fragility of life, which is one of its main themes. There are arguments to be made for O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night or Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire or Tony Kushner's Angels in America or Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, but I think Thornton Wilder's Our Town trumps them all with its incongruous simplicity as it taps into each chronic playgoers complexity of emotions regarding his or her own life's experiences. It is the most resonant of American dramas.

The most truthful and tragic of all American plays is Our Town. In fact, I consider it the greatest American play of the 20th Century and it is appropriate to be writing about it when discussing the fragility of life, which is one of its main themes. There are arguments to be made for O'Neill's Long Day's Journey into Night or Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire or Tony Kushner's Angels in America or Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, but I think Thornton Wilder's Our Town trumps them all with its incongruous simplicity as it taps into each chronic playgoers complexity of emotions regarding his or her own life's experiences. It is the most resonant of American dramas.

An aside: I interviewed Edward Albee recently for the sequel to my memoir, Mississippi Sissy. We got to talking about Wilder, who was a kind of mentor to him. "I started out writing poems when I was about eleven," Edward told me. "I stopped writing poems when I started writing plays when I was 27. I showed some of my poems to Thornton Wilder. I knew him rather well, though he was a very, very closeted and tortured gay man. Very closeted. You could say it was the times. But it was the man too. He read the poems and offered some succint advice: 'Perhaps, Edward, you should write plays.'"

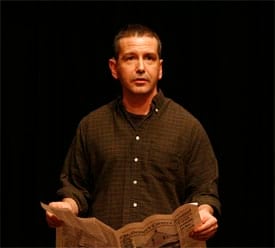

The emotional succinctness of Our Town is certainly highlighted in the revelatory production it is now receiving at the Barrow Street Theatre in Greenwich Village. It is one of the most stunning productions I have seen in years and if you love the theatre you would be remiss if you skipped it because of memories of being bored by other productions of the play — in high school or college or community theatre. This production, which was originally staged at Chicago's Hypocrites Theatre, by director David Cromer, will shake away the cobwebs of any bad memories you have of thinking the play is hackneyed or dated. Cromer — who did such a stunningly effective job of directing the musical of The Adding Machine last season — even plays the Stage Manager himself in this production. "This is the way we were," he recites Wilder's lines but has staged it to remind us that this is the way most decidedly are. Indeed, Cromer's name is as big as Wilder's on the front of the program — and rightly so. He has taken the play and mined it for its essential truths. He has also cast it exquisitely. The actors could not be bettered. And, at the end, there is a coup de theatre that is so organic to Wilder's intentions and yet so surprising it will take your breath away.

The emotional succinctness of Our Town is certainly highlighted in the revelatory production it is now receiving at the Barrow Street Theatre in Greenwich Village. It is one of the most stunning productions I have seen in years and if you love the theatre you would be remiss if you skipped it because of memories of being bored by other productions of the play — in high school or college or community theatre. This production, which was originally staged at Chicago's Hypocrites Theatre, by director David Cromer, will shake away the cobwebs of any bad memories you have of thinking the play is hackneyed or dated. Cromer — who did such a stunningly effective job of directing the musical of The Adding Machine last season — even plays the Stage Manager himself in this production. "This is the way we were," he recites Wilder's lines but has staged it to remind us that this is the way most decidedly are. Indeed, Cromer's name is as big as Wilder's on the front of the program — and rightly so. He has taken the play and mined it for its essential truths. He has also cast it exquisitely. The actors could not be bettered. And, at the end, there is a coup de theatre that is so organic to Wilder's intentions and yet so surprising it will take your breath away.

I'll admit I began to cry during the choir rehearsal in the first act and was teary the rest of the play. By the end, I was close to sobs. I don't want to spoil it for you with too much description or to be too over-blown with my praise. But any reader out there who loves the theatre should get down to Barrow Street promptly. Because of the demand for tickets in the small space, the run has been extended already through September. But be warned — be prepared to experience the play, not just to watch it.

T T T T (out of 4 possible T's)

Our Town, Barrow Street Theatre, 27 Barrow Street, New York. Ticket information here.

***THE AMERICAN PLAN

There are two other productions worth catching — both produced by the Manhattan Theatre Club. At first, I thought that the two plays could not be more different. But then I realized at their roots they are about survival and how, at times, the most beastly of maternal influences can be the very impetus that propels us to survive.

Continued, AFTER THE JUMP…

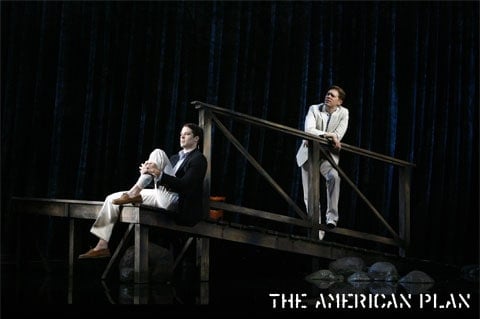

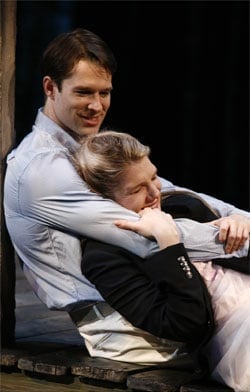

At the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, MTC's Broadway outpost, you have this one last weekend to catch Richard Greenberg's The American Plan starring one of Edward Albee's favorite actresses, Mercedes Ruehl, as the maternal presence whose beastliness has been caused by her own survival of the Holocaust.

At the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, MTC's Broadway outpost, you have this one last weekend to catch Richard Greenberg's The American Plan starring one of Edward Albee's favorite actresses, Mercedes Ruehl, as the maternal presence whose beastliness has been caused by her own survival of the Holocaust.

With echoes of other beastly maternal narratives — The Glass Menagerie, Suddenly Last Summer, Light in the Piazza — Greenberg has fashioned a play about emotional subterfuge and a kind of warped devotion that lashes the loved to those who love them for all their own convoluted reasons. Most of the play takes place in the Catskills one summer right before the dawn of the 1960s and there is that sense of inchoate freedom – sexual and political — covering the play like some mist off a Catskills lake.

Ruehl is riveting in the role of the monstrous mother with the thick German accent — yet I was never sure if she was riveting because she was so good or because she was so bad. But I often have that response to her. Lily Rabe who plays her daugher, who is lashed with all that maternal love, is becoming one of our most enchanting stage actresses. And there is beefcake to behold in the first lakeside scene and a gay subplot as well. It's all a bit diffuse finally, but definitely a fine production — directed by David Grindley — of a flawed early Greenberg play.

T T T(out of 4 possible T's)

The American Plan, Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, 261 West 47th Street, New York. Ticket information here.

***RUINED

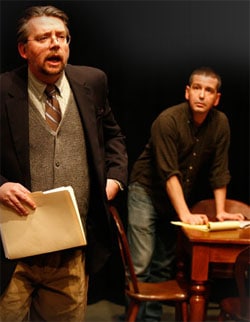

I was spellbound from beginning to end by Ruined at New York City Center Stage I, MTC's outpost on 55th Street. Written by Lynn Nottage and directed by Kate Whorisky, it is another transfer from Chicago, this time from the Goodman Theatre.

I was spellbound from beginning to end by Ruined at New York City Center Stage I, MTC's outpost on 55th Street. Written by Lynn Nottage and directed by Kate Whorisky, it is another transfer from Chicago, this time from the Goodman Theatre.

Set in the bar/whore house in a small mining town in the Ituri Rainforest of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the play is exotic in its locale and yet its dramatic concerns are more commonplace — how do its protagonists emotionally survive in a world that is cruel and increasingly loveless?

Nottage has fashioned a singular drama from this commonplace concern as she — through the beauty of her language and the visceral use of African music and songs — takes us on an emotional journey with the madam of the whorehouse and her girls who have been "saved" after being repeatedly raped at the hands of war-weary soldiers.

Nottage has fashioned a singular drama from this commonplace concern as she — through the beauty of her language and the visceral use of African music and songs — takes us on an emotional journey with the madam of the whorehouse and her girls who have been "saved" after being repeatedly raped at the hands of war-weary soldiers.

Again, this is yet another exquisite cast of actors, which includes the almost eerily beautiful daughter of Phylicia and Ahmad Rashad— Condola Rashad — making her New York debut as one of the “ruined” women of the title. Saidah Arrika Ekulona as Mama Nadi, the madam of the house — kind of Congolese Mother Courage — so seamlessly becomes her character that one forgets at times one is watching a performance. But it is Russell Gebert Jones, as the one kindhearted man in the play, who will steal your heart just as he finally does Mama Nadi's in the show's slightly sentimental — though profoundly hard-earned — finale. Bravo to all concerned.

T T T T (extended through May 3rd)

Ruined, New York City Center, Stage I,131 West 55th Street, New York. Ticket information here.

Recently…

A Conversation on 33 Variations: Kevin Sessums Talks to Jane Fonda and Moises Kaufman [tr]

On the Stage: Becky Shaw and The Third Story [tr]

On the Stage: Pal Joey and Hedda Gabbler [tr]

On the Stage: Billy Elliot, Shrek, 13, and Prayer for My Enemy [tr]

On the Stage: Back Back Back and Farragut North [tr]

On the Stage: Streamers and The Language of Trees [tr]