1. The Senate can take up a "clean" repeal of DADT in a lame duck session of Congress after the midterm elections. Senator Reid has indicated that he may pursue this option. The political viability of this option, given the impending electoral apocalypse everyone seems to think will pan out, is up in the air.

2. President Obama can issue an executive order halting implementation of the policy until the Defense Department has completed its analysis. This is what the gay left and the folks over at GetEqual want. The activists among us hunger for swift and decisive action and immediate changes to unjust laws. While I see some beauty in that black-and-white worldview, I cannot share it. My heart would welcome an executive order halting discharges under DADT, but my head would cringe just a little bit.

I am troubled by executive efforts to expand its authority. Liberals criticized the administration of President George W. Bush for its advocacy and implementation of the so-called "strong unitary executive", which essentially takes Article II of the Constitution to the extreme. A strong executive would let the president control every inch of the executive branch, minimize the role of Congress in the appointment of executive branch officials and even outlaw independent prosecutors (like during Watergate) and independent agencies (like the FDA) because they are outside the control of the presidency. Progressives and their allies in Congress also criticized then-Judge Alito for his appellate court decisions that seemed to advance a super strong theory of the executive branch.

As Dawn Johnsen has noted, President Bush put the unitary executive theory into his signing statements 363 times when he felt that legislation interfered with his power. Often, President Bush justified his robust conception of the executive on the Commander in Chief Clause (U.S Const., Art II, Sec. 2, clause 1), which states as follows:

- The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States; he may require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Office, and he shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.

This clause bestows pretty broad powers on the president. It makes sense that it does because of the nature of military order, discipline and chain of command.

But I find the justification lacking. As Professor Cass Sunstein has noted, no one doubts that the Framers created a unitary executive to some extent. The question is to what extent, or how strong or how weak. The president's powers seem their strongest when he wears his Commander in Chief hat, as that clause is clear, broad and understandable given the nature of military power.

In other areas, the president's power is justified by the Vesting Clause — "The executive Power [of the United States] shall be vested in a President of the United States of America" — and the Take Care Clause — "The President shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed…" These clauses, separate and apart from the Commander in Chief Clause arguably create a distinct source and a distinct sphere of authority for the president.

The very fact that the Commander in Chief Clause creates presidential power separate and apart from the Vesting/Take Care Clauses suggests that the extent of the president's power under one clause is not comparable to the power under the other. Nor is the language. The Commander in Chief Clause is clear — the president "shall" have power as a military "commander", he can give direct orders to his department heads and issue pardons. Those are specific and broad powers.

The Vesting and Take Care Clauses simply — and vaguely — assigns to the president the power to execute the laws. What that actually means is up for debate. The very vagueness of this source of presidential power lends itself to competing broad and narrow interpretations. But when seen in context — as a separate executive power source next to a supremely broad one — the strong unitary executive theory makes little sense to me. Why would there need to be two separate sources of presidential power if not to distinguish the type of power the president can wield in the two different areas? If we admit that a president's authority is always greatest when he's prosecuting a war, a president's other source of power, by virtue of its vagueness, its threat to checks and balances and the common understanding that the president is not a military-style commander in the civilian world, should necessarily vest him with fewer powers.

Therefore, the Bush Administration's liberal critics acknowledged that part of the President's duty is to "interpret what is, and is not constitutional, at least when overseeing the actions of executive agencies," but they rightly accused Bush of overstepping that duty. Those same progressives are now itching for a progressive president who came up in legislative branches of government to use that unitary executive power to intrude in an area of law where Congress has spoken. It is clear that President Obama has the power to issue an executive order halting discharges, and it is also clear that he could base any such executive order on the great power given to him under the Commander in Chief Clause because DADT involves the military, but the use of executive power in this way should be troubling to those who criticized President Bush's overreaching. I am struck by the left's short memories, at best, or outright hypocrisy, at worst, in this area.

2. The Justice Department could decline to appeal Judge Phillips ruling in Log Cabin Republicans v. United States, which declared DADT unconstitutional. Courage Campaign Chairman Rick Jacobs prefers this response. The Obama Administration need not appeal; there is no law, no executive order, no custom that requires the DOJ to appeal all rulings adverse to current law. But, gay rights advocates run into strategic and legal problems even if the Administration declines to appeal.

The federal government has always taken the position that precedent against it in a circuit only applies in the territorial jurisdiction of that circuit. After doing a little research and speaking with Jon Davidson of Lambda Legal, I have found cases where federal district courts have issued nationwide injunctions against the federal government's enforcement of statutes held to be unconstitutional. That is what the Log Cabin Republicans asked for in their successful DADT case before Judge Phillips in Riverside, CA. However, the federal government has also often taken the position that federal district court judges do not have that authority. The DOJ has argued that district judges can only bind those within the territorial jurisdiction of their districts and that appellate courts can only bind those states within their territorial jurisdiction. In fact, that is exactly what has happened in the case of the many challenges to DADT. Witt v. Department of the Air Force came out of the Ninth Circuit, which means that in the Ninth Circuit, any defense of DADT must meet strict scrutiny (a really high standard). But, Cook v. Gates, out of the First Circuit, found that DADT merits only intermediate scrutiny and found that DADT met that standard. Those decisions apply only within the respective territorial jurisdictions of the Ninth and First Circuits.

So, if the Obama Administration declines to appeal, a single district court injunction that has arguable precedential weight across the country may be a half-hearted victory for open service.

An executive order or a DOJ refusal to appeal Judge Phillips ruling would be pro-gay steps, but of varying legal and strategic benefit.

Having played devil's advocate here, I'd like to hear what you think. Do you agree? Do you feel that I am needlessly concerned with executive power and should welcome an executive order without hesitation? Or is it a legitimate concern given, for example, that a supreme executive can use its Commander in Chief powers to violate our Fourth Amendment rights in the name of the war on terror, or restrict what I can say or do under the guise of aiding terrorism? And, what of the appeal? Do you feel it is the best interests of repealing DADT to pursue appeal up the ladder? Or should the Obama Administration decline to appeal, leaving only a district court decision as our voice?

(image jeff sheng from a new exhibit at the kaycee olsen gallery)

Ari Ezra Waldman is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. After practicing in New York for five years and clerking at a federal appellate court in Washington, D.C., Ari is now on the faculty at California Western School of Law in San Diego, California. His areas of expertise are criminal law, criminal procedure, LGBT law and law and economics. Ari will be writing biweekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.

"I'm disappointed this happened." Agreed.

"I think [Senator] Harry Reid played politics with my rights." Yes and No.

"[President] Obama's a dick." Disagree.

"I'm voting with my feet and moving to Toronto." Excellent! So you can serve in the military and marry that lieutenant in B Company.

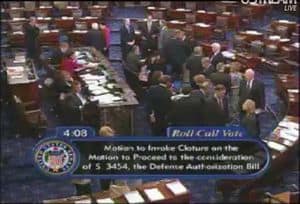

These are just a few of the comments (and my responses) from those around me today in the aftermath of the Senate's failure to muster sixty votes to invoke cloture on the Defense Authorization Bill.

These are just a few of the comments (and my responses) from those around me today in the aftermath of the Senate's failure to muster sixty votes to invoke cloture on the Defense Authorization Bill.

Those of us who served, those of us who currently serve and those of us who would serve if we were allowed to do so openly were dealt a blow today. And, we are fishing about for someone to blame. Some ardent opponents of DADT find it unreasonable to attach it to an omnibus bill that must pass; others say it will only pass that way. Some gay rights leaders deny that the issue of open service should be left in the legislative realm; they believe that reasoning about our rights is the purview of the judiciary. Many liberals are lashing out at Senator Reid for supposedly not allowing amendments and unfairly putting his own re-election prospects ahead of gay rights. And there are those who realize that Mr. Reid ran the vote like every majority leader before him and that Republicans were playing fast and loose with the truth when they justified their vote on the attachment of non-defense-related amendments to the bill. And then there's the vitriol directed against President Obama, arguing that he could have done more, that Hillary Clinton would have done better or that the president is a secret homophobe.

Blame is for children. Adults look ahead. The gay rights movement has been extraordinarily successful in changing the debate in our favor. Not thirty years ago, homosexuality was a disease, something to be cured, a dirty mental illness. Professor Andrew Koppelman of Northwestern University notes that today, it is that antiquated view of gay people that has become stigmatized. And President Obama has done his part. Jennifer Pizer of Lambda Legal notes that having the president speak so forcefully on behalf of gay rights — stating his opposition to DADT and DOMA, noting how much harm they cause — has helped shift the discussion from justifying discrimination to how to end it. We might have wanted the "how" to be a bit easier, but to ignore the dynamic shift in dialogue since Stonewall is to let one's current disappointment cloud all rationality. And we cannot forget our great successes in the courts, from Lawrence v. Texas to Perry v. Schwarzenegger to Log Cabin Republicans v. United States to today's ruling out of Florida declaring that state's gay adoption ban unconstitutional.

Still, we wonder where we go from here. Options and analysis (and a chance for you to discuss these issues) AFTER THE JUMP…