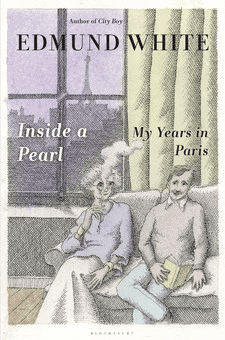

Reading Edmund White's fascinating, vital new memoir, which covers the fifteen years he spent in France in the 1980s and 90s, feels a little like attending the world's most fabulous cocktail party. The pages are filled with impossibly glamorous people doing impossibly glamorous things, from literary lights like Susan Sontag and Julian Barnes and Alan Hollinghurst, to celebrities of a different stratosphere, like Lauren Bacall and Tina Turner and Yves Saint Laurent.

At the center of it all is White, who for four decades has been, in both fiction and nonfiction, our preeminent chronicler of gay life. When the period covered by Inside a Pearl begins, in 1983, White has just published his classic novel A Boy's Own Story, and he arrives in Paris armed with that success, as well as high school French and sixteen thousand dollars from a Guggenheim Fellowship.

At the center of it all is White, who for four decades has been, in both fiction and nonfiction, our preeminent chronicler of gay life. When the period covered by Inside a Pearl begins, in 1983, White has just published his classic novel A Boy's Own Story, and he arrives in Paris armed with that success, as well as high school French and sixteen thousand dollars from a Guggenheim Fellowship.

He's wonderful at describing the disorientation of those first months, and especially at conveying linguistic struggles that will be familiar to anyone who has lived abroad: “After I'd present my own carefully displayed sentence like a diamond necklace on black velvet, the other speaker, the French person, would throw his sentence at me like a handful of wet sand. It would sting so badly that I'd wince, and an instant later I would wonder what had just happened to me.”

White quickly finds his feet in Paris, working for Vogue, learning the language, and writing his books, among them a brilliant biography of the gay novelist Jean Genet. Nor were all of his pursuits literary: as in all of his work, White speaks with breathtaking candor in these pages about his sexual life, including innumerable tricks and a number of longer affairs. He can be deliriously indiscreet, as when he talks of first meeting the great British novelist and travel writer Bruce Chatwin, when the two of them quickly found themselves “sniffing each other's genitals like dogs.”

Inside a Pearl has a loose, associative structure, and you may find yourself frustrated if you read it looking for a clear narrative organizing the book. Instead, there are many small narratives, wonderful anecdotes and asides and ruminations. White refers to himself at one point as an “archaeologist of gossip,” and the book might best be approached as a collection of particularly inspired gossip: sometimes a bit scandalous, almost always good-hearted, and thoroughly entertaining.

This isn't to say that the book lacks pathos or weight. White weathers the most intense period of the AIDS crisis in Paris, and while he writes that he hoped to find there “an AIDS holiday, a recess from the emergencies of the disease,” he instead finds that “Death was my constant shadow.” One of the founders of Gay Men's Health Crisis, as well as its first president, White received his own diagnosis in Europe, when he and his lover at the time got tested together. His lover was negative, White was positive; the night after learning his status, he was “in anguish and couldn't sleep, not because I was afraid of dying but because I knew my wonderful adult romance…was doomed.”

The book's most moving sequence tells the story of White's relationship with Hubert Sorin, whom he fictionalized in his novels The Farewell Symphony and The Married Man. When Hubert becomes ill, White cares for him through an agonizing decline. Not least among the torments of White's long vigil over Hubert's dying is the fear that he might himself have infected his lover. (Doctors eventually reassure White that this wasn't the case.) Though only a few pages long, White's account of his final trip with Hubert to Morocco, during which Hubert collapses and eventually dies in a clinic where the hostile nurses are amused by his “pitiful state,” is a devastating portrait of grief.

While White writes both movingly and amusingly of his lovers, his real genius is for friendship, and it's the portrait of a great friend that spans the book and gives it its greatest sense of coherence. White first met Marie-Claude de Brunhoff in 1975, and it's her friendship that he credits with his discovery of France. Witty, insecure, elegant, Marie-Claude—“MC,” as White calls her—is a recurring presence in the memoir, as White helps her survive her abandonment by her husband (Laurent de Brunhoff, who continued the Babar books begun by his father) and remains at her side as she battles, at first successfully, the cancer that on its return would cause her death in 2008.

MC is an artist—she makes Joseph Cornell-like boxes—but it's her person and her life that White admires as her greatest creation. In the book's first paragraph, he says that on their first meeting she “gleamed like the inside of a nautilus shell,” an image that echoes the memoir's title. It also echoes an idea of the French philosopher Michel Foucault, whom White knew: at the end of his life, White writes, Foucault came to believe that “the basis of morality after the death of God might be the ancient Greek aspiration to leave your life as a beautiful, burnished artifact.”

MC is an artist—she makes Joseph Cornell-like boxes—but it's her person and her life that White admires as her greatest creation. In the book's first paragraph, he says that on their first meeting she “gleamed like the inside of a nautilus shell,” an image that echoes the memoir's title. It also echoes an idea of the French philosopher Michel Foucault, whom White knew: at the end of his life, White writes, Foucault came to believe that “the basis of morality after the death of God might be the ancient Greek aspiration to leave your life as a beautiful, burnished artifact.”

It's an appealing idea to anyone who has spent his life, as White has, in the service of art. Inside a Pearl is a beautiful, hugely endearing, often brilliant book, a worthy record of White's attempt to be true to what he sees as the several purposes of his life: “to teach, to trick, to write, to memorialize, to be a faithful scribe, to record the loss of my dead.”

Previous reviews…

Randall Mann's ‘Straight Razor'

Janette Jenkins' ‘Firefly'

Gengoroh Tagame's ‘The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame'

Jason K. Friedman's ‘Fire Year'

Garth Greenwell is the author of Mitko, which won the 2010 Miami University Press Novella Prize and was a finalist for both the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award and a Lambda Award. He is currently an Arts Fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop. Connect with him on Facebook and Twitter.