BY PAUL HUNTER

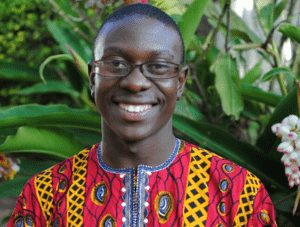

Last Friday, Richard Lusimbo woke up to discover his face on the front of the Ugandan tabloid, Red Pepper, which had been outing known homosexuals all week. The headline beside Lusimbo's photo read "How I became Homo."

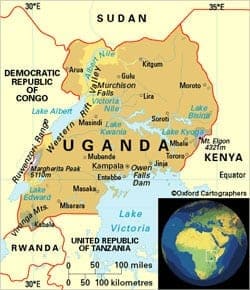

Lusimbo is the research manager for SMUG (Sexual Minorities in Uganda – Facebook) and as of last Monday, February 24th, his organization was officially declared illegal when President Museveni signed the Anti-Homosexuality Law. I caught up with Lusimbo last week after he spoke on a panel at RightsCon in San Francisco, a conference hosted by Access, an international human rights organization that defends and extends digital rights of users at risk around the world.

Lusimbo is the research manager for SMUG (Sexual Minorities in Uganda – Facebook) and as of last Monday, February 24th, his organization was officially declared illegal when President Museveni signed the Anti-Homosexuality Law. I caught up with Lusimbo last week after he spoke on a panel at RightsCon in San Francisco, a conference hosted by Access, an international human rights organization that defends and extends digital rights of users at risk around the world.

"What happened when you discovered your face on the front of Red Pepper?" I asked Lusimbo.

“At that moment I felt weak, not because I was scared for being outed, I felt weak because I didn't know what the reaction was going to be; the info was misleading.

“When I logged onto Facebook I found so many hate messages. ‘If I see you I'm going to kill you. You are such a disappointment.' I had to deactivate my Facebook account. My phone wouldn't stop ringing. My father was very disappointed. He always said, be whoever you are, do what ever you do, but don't be in the media and there I was being exposed.”

Lusimbo could not walk around in public. He had his passport renewed for his trip to the U.S., but couldn't go to the passport office to pick it up; a friend went for him. He was afraid that the authorities would think he needed his passport to travel around to promote homosexuality. He ended up missing his flight, and left on Saturday.

Since then his life has turned upside down. His high school, where he was a student leader, wants to erase him from their records. Some family members don't want to talk to him anymore. Some of his friends are shunning him and sending him hate messages.

Said Lusimbo: “I feel scared and threatened for my life because this kind of exposure is not the kind you want. It puts you at risk – calls for action from the society and the community to act, to take you down as the evil, so that is why I fear. The community that we live in is the most dangerous because people could do anything. The mere fact that Museveni has signed the bill, they think it is ok for them to do anything to you because the law says so; that is the greatest fear I live under now.”

Yet Lusimbo has no fear of allowing us to publish his photo: "At this point in time, I have been outed twice in the newspapers and each time it has happened it has come with its new challenges. I am already a face for the LGBTI in Uganda and so my picture appearing would be of no problem, although I can't limit how the tabloids would choose to use it next time."

Yet Lusimbo has no fear of allowing us to publish his photo: "At this point in time, I have been outed twice in the newspapers and each time it has happened it has come with its new challenges. I am already a face for the LGBTI in Uganda and so my picture appearing would be of no problem, although I can't limit how the tabloids would choose to use it next time."

Lusimbo is returning to Uganda anyway.

"At the end of it all, home is home," he said. "I have friends around the world who are worried about me returning, so are several in Uganda, and they have offered to support me in whatever possible way to stay safe here, but leaving home (Uganda) is not that easy. I have my whole life there, family and friends, the work that I love so much – thinking about all that makes me more determined than ever to return home. I amplify the voice of my people whose voice wouldn't be heard if I left. I want to contribute to the development of Uganda like any other citizen, and I can only do that when there."

What is life like for LGBTI people in Uganda?

“People live in fear. It is not easy to come out to family or to say you are gay… you don't give accountability to just your father or your family, but to your whole clan and the church.

“The Evangelicals have a big influence in Ugandan society and have taken to the pulpit to preach hate. Given this kind of homophobia and discrimination, people are scared. For example, if we organize a pride parade, very few people would want to come out. They don't want to be outed. They don't want to be activists because they are being put at risk. People tend to stay to themselves.

“People have dropped out of school and are therefore not economically empowered and are not well educated. It is hard for them to get jobs. And at work you are working as an illegal person and in your own community you are an outcast.”

LGBTI people are also being denied services in hospitals. Lusimbo said: “There have been surveys showing that LGBTI people within these communities have a high risk of getting HIV AIDS and living positive. People can't walk into a health facility with their boyfriend and say, ‘I have come for HIV testing.' I'd be thrown out of the hospital with my partner. If I say I'm HIV positive, I won't get the proper medicine.”

Lusimbo added, “Tabloids, like Red Pepper, have made it very difficult. Their coverage is biased and they misrepresent. Ugandans are only hearing one side of the story, promotion and recruitment; that homosexuals are promoting the evil in the society. The only place where we have been able to give the other side of the story has been online and through foreign media.”

Lusimbo added, “Tabloids, like Red Pepper, have made it very difficult. Their coverage is biased and they misrepresent. Ugandans are only hearing one side of the story, promotion and recruitment; that homosexuals are promoting the evil in the society. The only place where we have been able to give the other side of the story has been online and through foreign media.”

Lusimbo said they continue to see LGBTI people being arrested by the police and charged with no offence. Instead, the police contact the media who show up to document the event. This makes it very difficult for people arrested to return to their communities where they live, sometimes forcing them to relocate.

“The LGBT community in Uganda is not well resourced,” said Lusimbo. SMUG offices have been raided several times. Some of the information gathered from these raids has appeared in Red Pepper and other tabloids. It has been difficult for them to operate as a full-fledged organization.

What impact will countries cutting foreign aid, based on the anti-homosexuality bill, have on Ugandans, particularly the LGBTI population?

“If aid is just cut in general terms, the local person is going to suffer. This includes LGBTI people. It will promote the isolation of the LGBTI community and we will continue to be marginalized. People like David Bahati that have been promoting homophobia are going to go on the radio and say, ‘Look, people are dying because of the homosexuals. We can't have medicine in hospitals because of homosexuals. We can't have good water because of homosexuals.' These are government responsibilities but because our economy hasn't reached a point where President Museveni can support this, we are still depending on foreign aid.”

Lusimbo added: “We need to look at sectors where the government will feel a direct pinch. If that funding that the US gives to the army, if that were stopped, then that would have a direct effect. Donor countries should rethink and go back to the drawing table and look at how they could actually fund.”

The concern is if aid is cut due to the anti-homosexuality bill, the pinch could have a trickle down effect on Ugandan taxpayers, Lusimbo said. “We have seen billions disappear in scandals. The money sent through the prime ministers office to support the development of Northern Uganda, didn't go to any work, it was just swindled away. Ugandan taxpayers money was used to pay it back.”

What can American LGBTI people do to help?

“People should continue to air their disapproval of such a law and show their dissatisfaction. To continue to highlight not only LGBTI rights, but to talk around the whole diminishing space of the civil society in regards to human rights, Lusimbo said. "Continue to ask your leaders, president Obama and other influential people to not show their dissatisfaction by halting talks with the Ugandan government, but should open up a dialog around this issue."

Finally, Lusimbo suggested, "Support organizations who support people at risk and appeal to the American government to look into giving asylum for LGBTI people who would want to seek refuge in the US."