Back in June, I argued that there may never be a need for the Supreme Court to take a marriage equality case.

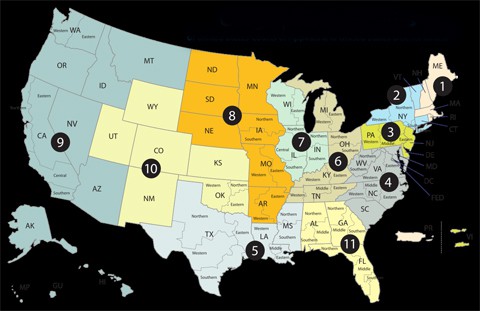

We have marriage rights in Washington, Oregon, California, New Mexico, Minnesota, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, Utah, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Indiana, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. The Ninth Circuit just declared the bans on marriage equality in Idaho and Nevada unconstitutional. Both states will have to comply in short order. Since there is no reason to stay those cases given the Supreme Court's recent denials of review, we will soon have marriage equality in at least 32 states!

The Supreme Court has denied review in cases out of the Fourth, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits. That leaves marriage equality lawsuits on appeal at the Fifth (the Texas case) and Sixth (the Michigan case). Marriage equality is almost a sure bet in, at least, the entire Ninth Circuit now.

At some point, the conventional wisdom says, all these cases will lead back to the Supreme Court.

Not necessarily. Looking at the map and our string of marriage equality victories, I wonder whether we will need the Supreme Court at all. A nationwide freedom to marry could be a fait accompli without five justices of the Supreme Court.

I make the argument AFTER THE JUMP…

The Supreme Court takes a small fraction of the cases sent to it. Even as that fraction gets smaller every year, there are several rules of thumb to help us determine when the Court will actually grant certiorari and hear a case.

The strongest indicator of a Court-worthy case is a "circuit split." A circuit split is just what it sounds like: a split, or disagreement, among the circuit courts of appeal. When two or more appellate courts have a different interpretation of a single legal issue, the law is unstable, and the Supreme Court steps in to provide the final word, re-establishing stability.

We have such a situation right now with respect to a part of Obamacare. Most courts have found that the entirety of the language of the Affordable Care Act extends subsidies to low income Americans seeking health care on both exchanges operated by the states and those operated by the federal government. A three-judge panel hijacked by politically motivated conservatives on the D.C. Circuit said otherwise, taking advantage of an inartfully drafted sentence in a massive law to create an absurd result. This circuit split might be resolved soon, when an en banc panel of the D.C. Circuit corrals its wayward panel of conservatives. But for now, the D.C. Circuit and other circuits have a disagreement. Someone needs to step in and declare who's right.

When there is no circuit split, there is no need for a final arbiter to come in and settle the disagreement. That is what may happen with marriage equality. There is indeed no circuit split here.

There are several reasons why all applicable circuits may agree and create, piece by piece, a nationwide right to marry.

There are several reasons why all applicable circuits may agree and create, piece by piece, a nationwide right to marry.

First, three circuits are already in the fold through a combination of litigation, legislative vote, and plebiscites. Marriage equality exists in all jurisdictions covered by the First, Second, and Third Circuits.

Second, we have won at the appellate court level in the Fourth, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits. And, at the Ninth Circuit, which is the largest circuit in the country, the appellate court has affirmed that any discrimination against gays merits heightened scrutiny. That means that any marriage equality ban in the Ninth Circuit will be nearly impossible to maintain. That's seven circuits out of eleven, leaving the Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, and Eleventh. The Eighth and Sixth Circuits are of particular note.

Some say the Eighth Circuit creates a circuit split. That is wrong. An old, pre-Windsor case, Citizens for Equal Protection v. Brunning, from the Eighth Circuit does not create a circuit split even though it allowed Nebraska's ban on marriage equality to stand. That case did not raise the underlying issues of the unconstitutionality of a marriage ban per se.

The Sixth Circuit, which held a marriage equality hearing recently, is the one to watch, according to Justice Ginsburg. But the Supreme Court's denial of hearings in the Fourth, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits has, quite literally, nearly surrounded the Sixth Circuit geographically (on three sides) with marriage equality jurisdictions. That strikes me as a taunt, a dare to the conservatives on the Sixth Circuit: We dare you to defy what we just did!

Third, despite the obstinacy of the Republican minority in the Senate, the President has done a remarkably good job rebalancing the federal judiciary away from the conservative turn of the George W. Bush years. The Eleventh Circuit is overwhelmingly an Obama (and Clinton) court with a proven track record of progressive decisions.

Fourth, marriage equality is an increasingly bipartisan position among judges. Republican judges at the district and appellate levels have written some of the most eloquent proequality decisions. We cannot, therefore, look at the 10-4 Republican-to-Democratic make up of the Seventh Circuit or the strong conservative tilt of the Deep South's Fifth Circuit or the Sixth and Eighth Circuits and conclude that the marriage equality winning streak is doomed.

Fifth, judges who have yet to hear marriage equality appeals do not exist in a vacuum. They see a rising tide of proequality rulings below them — at the district court level — and above them — at the Supreme Court (Windsor). They also see state court rulings and growing majorities of Americans supporting marriage equality. They also have the lessons of history. The Governor George Wallaces who literally stood in the way of racial equality do not get positive historical treatment. Judges know that marriage equality opponents are going to be forgotten, at best, and ridiculed or despised, at worst.

Fifth, judges who have yet to hear marriage equality appeals do not exist in a vacuum. They see a rising tide of proequality rulings below them — at the district court level — and above them — at the Supreme Court (Windsor). They also see state court rulings and growing majorities of Americans supporting marriage equality. They also have the lessons of history. The Governor George Wallaces who literally stood in the way of racial equality do not get positive historical treatment. Judges know that marriage equality opponents are going to be forgotten, at best, and ridiculed or despised, at worst.

And, sixth, they can read Windsor and should be inclined to think that Justice Kennedy, though, naturally, not explicit, would side with the progressive wing of the Court to support marriage equality. Rejecting equality simply to punt the case to Kennedy's desk smacks of weakness or lack of imagination.

Granted, the Supreme Court can take a case for many reasons, some of them unspoken, many of them shrouded in mystery: if it wants a case, it will take it. But, at least when it comes to the rule of thumb that you need a circuit split to get to the Supreme Court, the course of marriage equality litigation in the federal courts looks like it may find circuit unity and never need the Court at the end.

***

Follow me on Twitter and on Facebook.

Ari Ezra Waldman is a professor of law and the Director of the Institute for Information Law and Policy at New York Law School and is concurrently getting his PhD at Columbia University in New York City. He is a 2002 graduate of Harvard College and a 2005 graduate of Harvard Law School. Ari writes weekly posts on law and various LGBT issues.