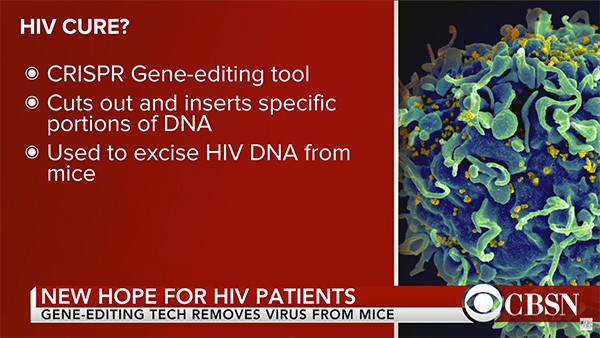

Researchers from Temple University and the University of Pittsburgh have utilized an innovative gene-editing procedure known as CRISPR to eliminate the presence of the HIV virus completely from infected mice.

In findings published this week in the journal Molecular Therapy, the researchers explained how HIV DNA, which can often remain latent and cause recurrence without warning, can be removed from a host's genome entirely to avoid further replication. This occurs with the aid of CRISPR/Cas9 technology, which uses an enzyme known as Cas9 in order to splice DNA at specific junctures.

As summarized in The Independent:

The scientists described how some of the mice had been “humanized” after being given some human immune cells. In these animals, “successful proviral excision was detected . . . in the spleen, lungs, heart, colon, and brain after a single intravenous injection” of the gene-editing protein.

Apparent breakthroughs in animal models often encounter problems later in the process of developing a treatment for humans. Nonetheless, the researchers . . . wrote in the journal that this type of genome editing “provides a promising cure for HIV-1/Aids.”

“Here, we demonstrate the feasibility and efficiency of excising the HIV-1 provirus in three different animal models,” they wrote. “Excision of HIV-1 proviral DNA by [this method in a living animal] in solid tissues/organs can be achieved … [which is] a significant step toward human clinical trials. To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate the effective excision of HIV-1 proviral DNA from the host genome in pre-clinical animal models [using this method].”

Furthermore, the process could eventually be replicated in humans:

The researchers were excited by their findings and are optimistic about their next steps. “The next stage would be to repeat the study in primates, a more suitable animal model where HIV infection induces disease, in order to further demonstrate the elimination of HIV-1 DNA in latently infected T cells and other sanctuary sites for HIV-1, including brain cells,” Dr. Khalili concluded. “Our eventual goal is a clinical trial in human patients.”