For nearly a century, a massive mural by painter Victor Arnautoff titled “The Life of Washington” has lined the hallways of San Francisco's George Washington High School.

It may not be there much longer.

The mural “glorifies slavery, genocide, colonization, manifest destiny, white supremacy [and] oppression.” So said Washington High School's Reflection and Action Group, an ad-hoc committee formed late last year and made up of Native Americans from the community, students, school employees, local artists and historians.

It identified two panels as especially offensive. One shows Washington pointing westward next to the body of a dead Native American. The other depicts slaves working in the fields of Mount Vernon.

Because the work “traumatizes students and community members,” the group concluded that “the impact of this mural is greater than its intent ever was.” They are campaigning for its removal.

The idea that impact matters more than intention has informed debates about everything from microaggressions to cultural appropriation.

But when it comes to art, should impact matter more than intention?

As historians committed to preserving our cultural heritage – and as citizens invested in the power of art to engage the public – we see the growing chorus of voices favoring impact over intention as a dangerous trend, one that makes art more vulnerable to rejection, censorship or even destruction.

A radical work for its time

For most members of the Washington High School's Reflection and Action Group, the only message “The Life of Washington” sends is one of crushing, dehumanizing oppression.

What happens, though, when we examine the mural in the context of the life and times of the artist?

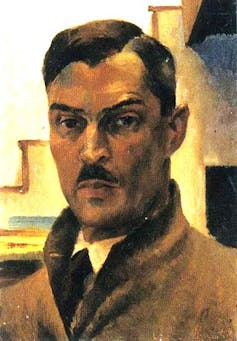

Painter Victor Arnautoff was born in 1896 in a small village in present-day Ukraine. He emigrated to San Francisco in 1925, where he joined a leftist art collective. During the Great Depression he was a supporter of workers' strikes and formally joined the Communist Party in 1937. He was even hauled before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956 for drawing a “Communist Conspiracy” cartoon that caricatured then-Vice President Nixon.

In “The Life of Washington,” Arnautoff decided to place Native Americans, African Americans and working-class revolutionaries front and center in the four largest panels, relegating Washington to the margins.

The slaves toiling in the Mount Vernon fields highlight a central paradox of America's history: The nation was founded by men who championed liberty, freedom and equality, and yet owned slaves.

Then there's the striking image of the fallen Native American. The mural's detractors say that it dismisses the humanity of indigenous peoples. But why must it necessarily be read as dehumanizing to Native Americans? Could it not instead be seen as throwing into sharp relief the inhumanity of the founding fathers?

According to Arnautoff's biographer, Robert W. Cherny, the image challenged the fallacy that “westward expansion had been into largely vacant territory waiting for white pioneers to develop its full potential.”

That the mural appears in a school is particularly important in this regard. For decades, the country's educational institutions perpetuated national myths about American exceptionalism and American history as one long glorious march of forward progress. Up until the 1960s, the standard U.S. history curriculum ignored the country's dark and terrifying history of racial violence, including enslavement and the slaughter of indigenous peoples. So drawing attention to the horrors inflicted on Native Americans and African Americans would have been a radical statement in 1930s America.

Many of those in favor of scrapping the murals seem to believe that merely depicting past atrocities justifies them. In fact, the Action and Reflection Group concluded that the mural contravened the San Francisco Unified School District's commitment to “social justice.”

Quite to the contrary. In our view, the “Life of Washington” provides an invaluable opportunity for students to engage in a serious and sustained way with social justice issues. There's a strong case to be made that Arnautoff is exposing – rather than celebrating – slavery and genocide. Moreover, those arguing for the mural's removal are overlooking the fact that African Americans are not only portrayed as picking cotton and that Native Americans are not only depicted as victims of genocide. Rather Arnautoff is insisting that African Americans and indigeneous peoples were key historical actors in the making of the United States.

Only the latest controversy

The controversy over this mural is sadly not an isolated exception.

Over the past several years, there have been dozens of cases where plays, poems, books, prints, paintings, sculptures, installations and other creative works have been shut down, canceled, removed or otherwise censored based on snap judgments, social media swarms, ideologically motivated reasoning and obtuse interpretations of the art in question.

In all of these cases, there has been little to no regard for the aspirations, aims and ambitions of the artists themselves. Their intentions have been treated along a spectrum that runs from indifference to contempt.

To be clear, we are not saying that an artist's intent is all that matters. How people interpret and respond to a work of art is inseparable from its raison d'etre.

But disregarding the intentions of artists would place every significant creative work with a whiff of controversy in jeopardy because of its “problematic” or “offensive” content. In a world where intentionality and context are irrelevant, satire and irony would not only be incomprehensible but forbidden.

Artist Kara Walker's searing paper cuts depicting the horrific violence of slavery in the United States? Nothing more than a celebration of the white domination of black bodies. The pungent, explosive litany of racial slurs in Spike Lee's “Do the Right Thing”? Just a vicious rehearsal of profoundly damaging ethnic stereotypes. Keegan-Michael Key's brilliant sketch character Luther who serves as Obama's “anger translator”? Simply a racist caricature of the “angry black man.”

What else becomes vulnerable to censorship?

Calls to censor “offensive” art by committees, petitions or the Twitterverse are especially dangerous. For every case of “righteous” censorship that removes works of art that are allegedly racist, sexist, homophobic and so on, there will be scores more censored on the grounds that they are anti-American or offensive to Christians.

As the American Library Association reports, the most frequently challenged and banned books are those that contain “diverse content” and include characters of color or address themes of sexuality, racism, religion, disability and mental illness.

Four out of the top 11 most challenged or banned books in 2018 were objected to on the basis of their LGBT content. “Two Boys Kissing” – a 2013 novel centered around the lives of seven gay teenagers – has made the American Library Association list for several years running, even though The Guardian described it as a “complex,” “intricate” novel “so extremely powerful [it] leaves you thinking long, long after you have finished reading it.”

Thinking long and hard, alas, is in short supply for members of the “we are not interested in the artist's intentions” when the art offends us brigade. Ripping art from its context degrades our critical faculties and imprisons us in the present. It smacks of a literal-minded authoritarianism that assumes and indeed insists that a creative work can and must only be read in one way.

When people refuse to see the contradictions, tensions and ambiguities of art, it becomes disposable. Arnautoff's detractors bring to mind Oscar Wilde's warning that any time a spectator of art tries to “exercise authority over it and the artist,” he “becomes the avowed enemy of Art and of himself.”

It took Arnautoff almost a year to complete the mural, painstaking labor that could be erased with a single coat of paint. Not only would this outcome whitewash history, it would also deal a severe blow to our own capacity for creativity and critical thought.![]()

Amna Khalid, Associate Professor of History, Carleton College and Jeffrey Aaron Snyder, Associate Professor of Educational Studies, Carleton College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.