Catholic Social Services. Lisa Keen unpacks it for us with commentary from friends and others. It seems they looked hard for a way to rule without precedent. And, In the end it's a lot like Masterpiece Cakeshop.

Was it a “significant” victory for LGBT people or another sign of “death by a thousand cuts” for LGBT equal rights? Was it an “important win for religious liberty” or a “failure”?

Reaction to the U.S. Supreme Court's June 17 decision in Fulton v. Philadelphia— allowing a Catholic foster care agency to refuse to obey a city non-discrimination ordinance— elicited an unusually wide range of often contradictory assessments.

One LGBT legal activist called it a “significant victory for LGBTQ people;” another called it “troubling.” One conservative commentator called it a “resounding victory for religious freedom,” while another lamented Fulton was a “failure by the high court to definitely end the ongoing governmental targeting of faith-based organizations.”

The Fulton decision did not deliver a straightforward message as Obergefell v. Hodges did in 2015, when the court said, “same-sex couples may now exercise the fundamental right to marry in all States.” It did not spell out clearly, as it did in Bostock v. Clayton last year, that, “An employer who fires an individual merely for being gay or transgender defies the law.”

a lot like Masterpiece.

Jenny Pizer, senior counsel and director of law and policy for Lambda Legal

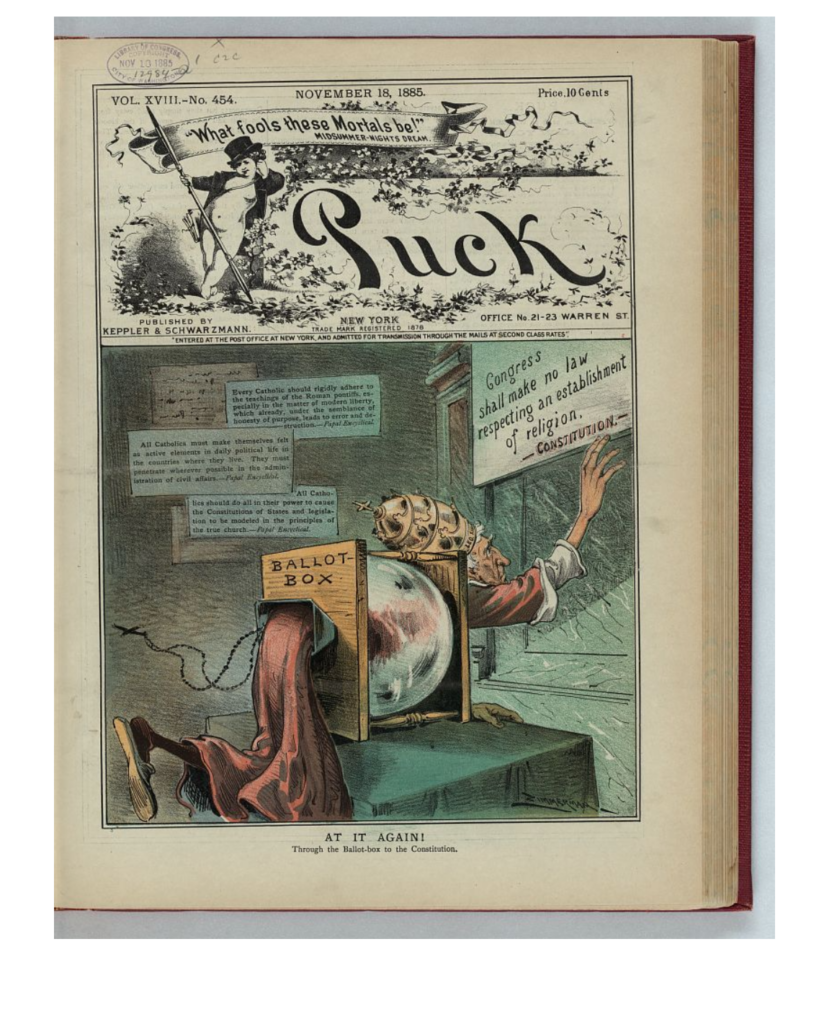

Instead, Fulton carried a nuanced message, akin to that of the Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado decision in 2018. In Masterpiece, the court ruled: “the laws and the Constitution can, and in some instances must, protect [LGBT people] in the exercise of their civil rights….At the same time, religious and philosophical objections to gay marriage are protected views and in some instances protected forms of expression.”

In Fulton, it said: “We do not doubt that [the city's] interest [in the equal treatment of prospective foster parents] is a weighty one, for [quoting from Masterpiece] ‘our society has come to the recognition that gay persons and gay couples cannot be treated as social outcasts or as inferior in dignity and worth.' On the facts of this case, however,” said Fulton, “this interest cannot justify denying [Catholic Social Services, or CSS] an exception for its religious exercise.”

“gay persons and gay couples cannot be treated as social outcasts or as inferior in dignity and worth…

this interest cannot justify denying [Catholic Social Services] an exception for its religious exercise.”

FULTON DECISION

“CSS seeks only an accommodation that will allow it to continue serving the children of Philadelphia in a manner consistent with its religious beliefs,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts, “it does not seek to impose those beliefs on anyone else.” Joining Roberts in the opinion were the three more liberal members of the court—Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan—and two of the court's newest conservatives—Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

The remaining three conservative justices—Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch—concurred in the judgment (that Philadelphia owed CSS an exception to its non-discrimination policy protecting LGBT people). But Alito and Gorsuch wrote their own concurring opinions, indicating they would have gone much further in ruling for CSS. And Thomas joined both.

The facts of the Fulton case are these: The city of Philadelphia has a city ordinance prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation and its contracts with outside organizations include similar language. City officials discovered that one of the private agencies to which it refers children in need of foster homes—Catholic Social Services (CSS)—had a policy of denying such placements to same-sex couples. When CSS's contract with the city came up for renewal, the city declined to renew it, saying CSS was in violation of the city ordinance and the contract's language. CSS sued, saying the city's refusal to renew its contract violated its First Amendment Free Exercise right. Besides, said CSS, it never violated the law because no same-sex couples had ever come to CSS and, if they had, CSS would have gladly referred them to some other foster care agency.

Finding escape clauses

Writing for the court, Chief Justice John Roberts accepted CSS's contention that, by certifying a family for potential foster care placements, it was making an “endorsement of their relationships.”

“CSS does not object to certifying gay or lesbian individuals as single foster parents or to placing gay and lesbian children,” wrote Roberts, noting that no same-sex couple had ever gone to CSS seeking to be certified. And he reiterated CSS's contention that, if a same-sex couple had gone to CSS, the Catholic agency would have directed the couple to an agency that does certify same-sex couples.

Jenny Pizer, senior counsel and director of law and policy for Lambda Legal, could not buy into that line of logic.

“Think about this in another area of law, like health care,” said Pizer. “If a doctor announces prospectively that they intend to discriminate—that they will treat only people of this one race and not another race—that's a discrimination problem. And maybe people hear that doctor's message and don't go to that doctor. But that doesn't absolve that medical office. You wouldn't have a decision saying that, ‘Lots of doctors in town are willing to treat black people so black people can just go somewhere elsewhere.' There has never been that kind of understanding of how civil rights laws are supposed to operate.”

Pizer said the Fulton decision is “a lot like Masterpiece.”

You wouldn't have a decision saying that, ‘Lots of doctors in town are willing to treat black people so black people can just go somewhere elsewhere.

Jenny Pizer, senior counsel and director of law and policy for Lambda Legal

“In both cases, it seems there was a search through the record to find reasons to allow the religious claim to win.”

In Masterpiece, that reason was a statement made by a member of the Colorado human rights commission during a hearing on a gay couple's complaint against a baker who refused to make them a wedding cake. The 7 to 2 majority said the commissioner's statement constituted “official expressions of hostility to religion” and that this hostility was “inconsistent with the First Amendment's guarantee that our laws be applied in a manner that is neutral toward religion.” Because the baker's religious beliefs did not receive a neutral hearing, the Supreme Court invalidated the claims against the baker.

In Fulton, Roberts relied on a statement in the city's contract that allowed the city's commissioner of health to grant an “exemption” of non-discrimination policies if it was in the best interest of a child.

the court did not rule (as the agency asked) that there is a constitutional right for government contractors … to discriminate…

James Essex, director of the national ACLU's LGBTQ & HIV Project

“It's not standard analysis,” said Pizer. “The evidence in Fulton was that Philadelphia enforced the law in a religiously neutral way, and the fact that there was a theoretical possibility of allowing an exception doesn't usually defeat the whole process.”

Roberts made two other arguments for his decision, too. One focused on the way Philadelphia's foster care system was set up: The city had custody of children in need of homes and asked its various foster care contractors to “certify” couples who could provide suitable homes. CSS said certification was tantamount to endorsement and claimed its religious beliefs were opposed to endorsing same-sex marriages. So, the city's insistence that CSS certify qualified same-sex couples “forced” CSS to choose between its religious beliefs and serving foster care children in Philadelphia. (The city had argued that CSS received $26 million per year for its services, “which is hardly something demonstrating religious hostility.”)