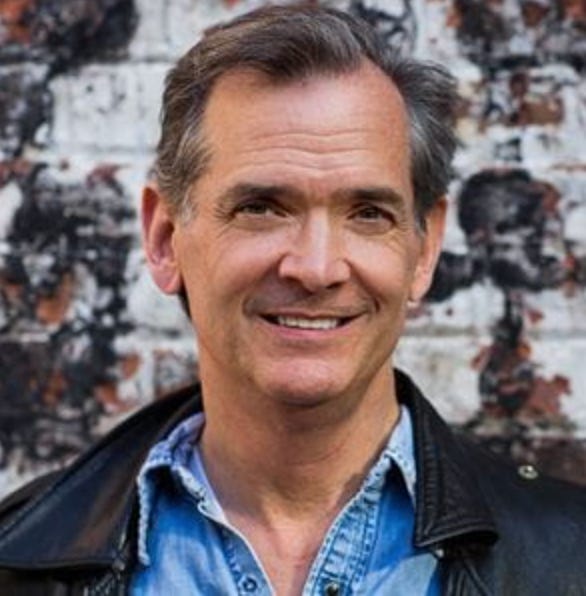

For two decades, the Atlanta-based HIV long timer has been putting all his shit out there with funny, unsparing honesty—and has built a massive readership along the way.

The Caftan Chronicles

Deep talks with notable gay men “of a certain age” about where we've been, who we are today and where we're going…

Vault the Wall SPECIAL.

I guess you'd call the following interview a special late-summer bonus round, because we already had porn entrepreneur Michael Lucas earlier this month, and I've already got someone really exciting lined up for both September and October. So here's my longtime fellow HIV/AIDS writer Mark S. King, GLAAD- and National Lesbian and Gay Journalist Association (NLGJA)-award winning author of the very popular blog My Fabulous Disease …and now, of a book out September 1 that's a compendium of the blog's best pieces, as well as pieces he wrote well before the blog, back in the 1990s. (You can pre-order it here; as well as keep track of where Mark will be appearing—including, of course, Caftan capitals Palm Springs and Wilton Manors—in coming weeks and months.)

Saucy Bits: Read on…

Diagnosed with HIV in 1985, Mark has taken a lifetime of ups and downs and turned them into a, well, fabulous collection of very pithy, witty, often brutally honest and self-critical short essays on everything from how we gay men are so good at shaming and judging one another for all sorts of things…to his gay brother's tale of helping his lover, who was dying of AIDS, end his own life with a Seconal cocktail…to what it was like starting his own gay erotic phone line in the 1980s…to how he's morphed into a total top who wants sex only a fraction as often as when he was young…to the shame of a relapse after a long period of time off crystal meth…to that time he appeared at 19 on “The Price is Right” to…well, you get the gist, which is that the essays range from quite raw and painful to utterly hilarious.

King has that perfect Oscar Wilde/Paul Lynde way with a quip: “I got The Clap so many times that I started calling it The Applause.” Or, marveling at how little sexual energy he has currently, at 62, compared to his youth, that these days, “ten minutes is a triumph of passion and stamina.”

I like Mark's writing because he doesn't shy away from examining aspects of himself that many of us gay men would rather look away from: His vanity, narcissism and need for attention. Things he's done in the past that have hurt people, including family members and lovers. Even what he sees as his own manipulativeness in seducing a 30-year-old man when he was 15—this in an age when we would almost unanimously agree that all the responsibility for a statutory-rape situation lies with the legal adult, not the child.

Brings Attention to Many Living with HIV

Thankfully, Mark can also realize that he has used his platform to bring attention to the challenges and accomplishments of people living with HIV other than middle-class white men like him- (and my-) self. His latest post, in fact, is called “How Do We Support Black Women in an HIV Arena Once Run by Gay White Men?”

Caftan Talk: Uncensored, a bit Raunchy, Candid and Funny.

What follows is my favorite kind of Caftan talk, uncensored and raunchy but also unsparingly candid, funny and self-deprecating. Thank you, Mark! Congrats on the new book! And thank you, readers! Now, as ever, I THANK those of you who pay for a subscription, which allows me the luxury of time away from my paid gigs in order to do this, and I ASK those of who free-subscribe to consider the $5/month version—if, indeed, you think it's worth it. It would mean a lot because I'm hoping to keep up this project for years to come.

Tim: Mark, thanks for talking to Caftan! So you and your husband Michael, a federal healthcare worker, live in Atlanta, yes?

Mark: As we speak, I'm surrounded by boxes because we're moving in a few days from an apartment in Midtown to a home in North Decatur. Michael's currently holed up in his home office and he doesn't come out until after five.

Tim: What's a typical day like for you?

Mark: My cat Henry wakes me up around 6:30am, but fortunately Michael feeds him breakfast and starts the coffee, so I can sleep longer. I stumble out around 7am, have my coffee and look at my emails. Or sometimes, if I'm writing something, if the solution I've been looking for occurs to me around 6:30am, I'm at the keyboard making it work even before I have coffee. If I'm in the zone like that, I can forget to have breakfast. But then I have my go-to daily conversations with usually two out of three people: my brother, Dick, who's gay and lives in Shreveport, Louisiana, with [TheBody.com writer] Charles Sanchez, and with my friend Lynn.

Then I go to the gym to work on any part of my body that is visible in a tank top. As long as my chest is bigger than my stomach, I'm fine. I play racquetball, so that takes care of the legs. Things like calves, you either have them or you don't. I know I should be doing yoga and stretching and working on what they call your core, whatever that is. At some point as I age it's going to be more important to be able to bend over and pick things up, not lift a large weight above my head.

Tim: Why don't you do any of that stretching and flexibility stuff?

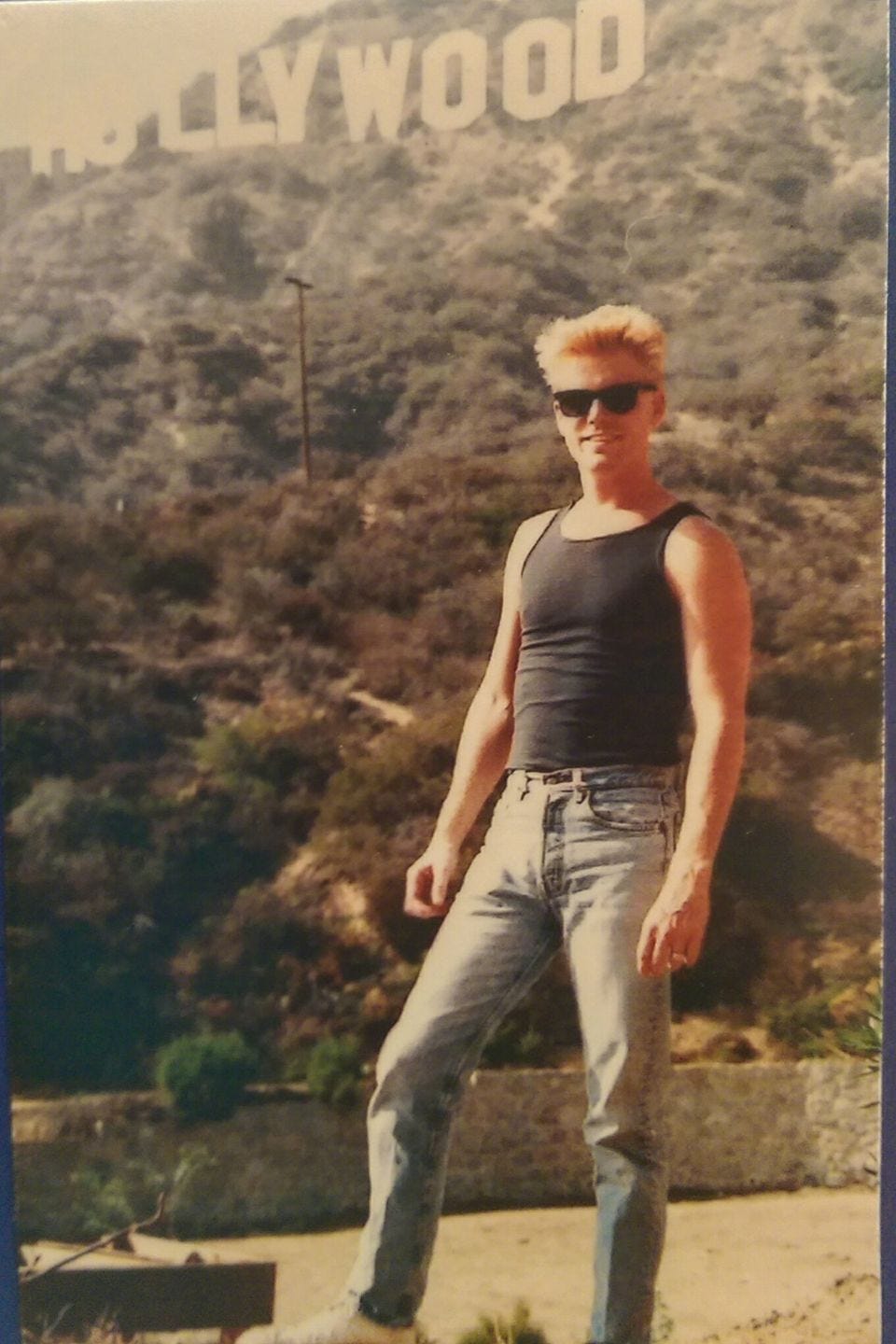

Mark: Because it's not visible in a tank top. I'm just being honest. I'm a child of the '70s, of button-fly jeans and a black tank. I'm a victim of gay culture, which means hanging on for dear life to upper-body musculature.

Tim: The happiest moment of my day is when I abandon the laptop and go to the gym. If it makes you happy, what's wrong with it?

Hanging on for dear life to upper-body musculature.

Mark: Nothing! I did a photo shoot for an article in HIV Plus that came out last month and I prepared for it like an Olympic event. I was going to the gym every day, I had my trainer, I was on my testosterone. As you can see, I wore a black tank top for the shoot.

Tim: Do you do steroids?

Mark: I have—I don't any more. Testosterone is not steroids.

Tim: Oh, I know. Why no more steroids?

Mark: Age, and the fact that they can damage your liver and kidneys. it's also true that taking testosterone has made my prostate the size of a grapefruit, but I haven't stopped that.

Tim: When you first went on testosterone, did you notice changes in your mood, libido and strength?

Mark: Yes, all those things. I take it because it works. I've been on it for 20 years. But I actually haven't been back to the gym since that photo shoot, and when I'm not working out, I deflate like a balloon. I feel like the Grindr hookup that doesn't look like his pictures.

Tim: What do you do the rest of the day and night?

Mark: Play with my cats and write a little bit. I sound like a man of leisure, and I kind of am. After Michael finishes work, we cook dinner. I'm a much better cook than I was when I met him. He taught me how to cook a chicken breast, which is to beat the hell out of it and put some Tony Chachere on it and grill it.

Tim: What is Tony Chachere?

Mark: It's Creole seasoning.

I can also make a whole chicken now. I know how to stick my fingers under the skin and shove in the butter and garlic. That is a major milestone for me. For a long time, I'd always choose partners who could cook and I was just the pretty one.

Then in the evening I'll go to a 12-step meeting because I'm in recovery, then I'll stay up too late watching horror movies, which Michael doesn't care for.

Tim: Which are your favorites?

Mark: Re-Animator if you want good cartoonish gore. Hereditary with Toni Collette is great for existential dread.

Tim: I love the first The Conjuring. Do you?

Mark: It's okay. They have to be a little sicker. For me, horror really means horrific, like I can't believe they've done that. I love gore that pulls no punches. In Hereditary, the little girl is decapitated, for God's sake.

Tim: Why do you love extreme horror films?

Mark: I like to be scared. They're an exciting ride. And they have a lot of creativity. Some of our greatest directors started in that genre. Look at Talk to Me, a great new horror movie directed by twins from Australia who have a YouTube channel called RackaRacka where they do outrageously violent, silly stuff.

Talk to Me is about a group of friend who entertain themselves by becoming possessed by this haunted hand. It's really almost about drug addiction—become addicted to the thrill of being possessed, and then what happens when they take it too far.

And then I go to bed around midnight.

Tim: Mark, you grew up Louisiana?

Mark: My dad was an Air Force officer so we lived all over the place, but when he retired when I was in fifth grade—I'm the youngest of six—we moved to Louisiana.

Tim: When did you start writing?

Mark: I wrote silly little stories when I was a kid, and then when I went to work for an AIDS agency in 1986, [the now defunct] L.A. Shanti, it was growing so fast that I became the media guy, the one writing the newsletter and press releases. But it's only been in the last 20 years that I've really been able to identify as a writer. The turning point was when I started writing My Fabulous Disease consistently. Prior to that, I'd write columns for Frontiers and then send them to different gay papers around the country who would print them.

Of all the editors I ever worked with, Bonnie Goldman, who founded [the HIV/AIDS site] TheBody, challenged me the most. “Why are you saying it this way?” she'd ask. She told me that the more warts, faults and doubts I revealed, the more I'd draw people in. She really worked for me and asked me to write a blog for TheBody.

It was after Bonnie left TheBody that I started My Fabulous Disease. I'd actually started it as a website to promote my first book, “A Place Like This,” and my web designer told me to blog on that page to keep it fresh and bring people to it. For a long time, I had to keep telling myself, “If you continue to build it, they will come.” Now, in a good month, I'll get 100,000 hits. I'll also share my content with HIV Plus, Poz—it doesn't matter. It's about building my brand, which is talking about myself. How self-centered can you get? [laughs] I often ask myself, “How have I gotten away with being a self-absorbed guy who writes only from my experience?” I think it's that I tell the truth about myself and let the chips fall where they may.

But along the way I've expanded the spotlight and written about other people and programs that interested me or that I wanted to cheerlead for.

Tim: One thing I like about your writing is that you are ruthlessly honest. What's been one good and one bad outcome of that?

Mark: Certainly I felt good about writing about addiction. I wrote a piece about a relapse I had when I was still dealing with its fallout. That felt good because I suffer, as many of us do, with imposter syndrome. I'd think, “If they only saw behind the curtain, that I struggle with drug addiction and have ruined relationships and have all sorts of wreckage in my wake, then they wouldn't like me anymore.” So to have been able to write that piece only days after coming to—some might say it's dangerous to write about such a thing so soon, but my writing is my therapy, my way of sorting out my own feelings. So I wrote it and then pressed the button.

Tim: What was the reaction?

Mark: Great. People said that they appreciated my honesty and that I would help others who were struggling. I was given love for something I thought I needed to keep hidden.

The one piece he's regretted and taken down…

Tim: Any pieces you've regretted?

Mark: I've only taken down a post once in all these years. It was called “Rescuing Michael Weinstein.” He's the much-maligned, deeply hated director of AIDS Healthcare Foundation. [Tim: He's largely disliked for taking contrarian views on things, such as calling the HIV prevention regimen PrEP a “party drug” and “a public health disaster in the making” when after it was first FDA-approved in 2012.]

So I wrote this fictional piece in which I was rescuing him from a sex club where he was having a crystal meth overdose in a sling. I thought it was hilarious.I was tying it into the general hypocrisy of gay men who deign to tell other gay men how to behave.

Within 20 minutes of my posting it, my good friend and mentor Sean Strub [founder of Poz magazine as well as Sero, which aims to repeal or modernize state laws singling out people with HIV who don't disclose their status before sex] called me.

He said, “I think you might want to think very carefully about that piece and what it may do. It's funny but it's also mean-spirited.” As soon as he said that, I realized I was wrong. I think he was trying to watch out for my reputation among people living with HIV, activists and public health folks. So I took it down after it had been up for three hours and had already been shared on list-servs. I replaced it with a note saying I regretted having written it and apologizing to Weinstein.

Tim: In your book, you have several pieces written about a decade ago or more about how we gay men tend to shame one another—how HIV-negative men shame positive men by using phrases like “drug- and disease-free” or “clean” and “you be, too,” or how older HIV survivors shame younger gay men for having tons of sex without condoms now that PrEP is available. Do you think in the years since you published those pieces, we've become a less shaming community overall?

Mark: You're right, I wrote a lot of that when social media and hook-up apps were inflaming various stigmas. Gay men are remarkably good at shaming our own—we've been shamed so much that we've developed claws of our own. I haven't been on hook-up apps the last ten years, so I can only go by conversations I have, which make me think that stigma is alleviating a little bit. But these things are generational. We were raised for decades in mortal fear of sex, which is a really powerful emotion that doesn't just go away with a scientific breakthrough like U=U [undetectable = untransmittable, the now-proven fact that people with HIV on meds with undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV sexually] or PrEP.

The Haves and Have-Nots: Bubbles of HIV Phobia

Tim: I feel like here in the heart of Brooklyn, HIV phobia has almost completely disappeared between U=U and PrEP. I'm open with my undetectable HIV status and hardly anybody has asked me to wear a condom in nearly a decade.

Mark: You might be living in a very well-informed bubble.

Tim: I admit it.

Mark: It's not the case across the country, even in places like Atlanta and Dallas.

Tim: I wanted to talk to you more about addiction. I too have a meth-using history but unlike you I've left the 12-step world after deriving a great deal from it for several years, because I realized I didn't want to be completely sober—I wanted to be able to have a drink or smoke some pot—and also because I really take issue with some of the Christian underpinnings and language of 12-step, like the idea of “surrendering” yourself to your addiction or giving up your “will.” Also, I know better than to say I'll never use meth again, but I did get to the point where dreading the actual horrifying, anxious, paranoid experience of using it overtook the so-called “euphoric recall,” the strong memory of the high, that makes so many pick up again and again.

What about you? What's your relationship today to addiction and recovery?

Mark: There's more than one way to skin a cat. People find health a number of ways. I think that 12-step programs like Crystal Meth Anonymous (CMA) are especially important for people who are acutely addicted and need help on a daily basis to sort themselves out and clear the wreckage. Where they go from there—there's all sorts of trajectories. Some may end up, like you, drinking or using some other substance occasionally. But I've learned my lesson and don't want to go back there. I need the constant reminder of what it was like. Also, I want to stick around to help somebody new. Being of service and getting out of my own self has been very helpful to me.

Having said that, I'm haunted by my drug addiction the same way I'm haunted by being an HIV longterm survivor. Both forever changed me. I have disturbing dreams and flashbacks. But also, some of my drug memories are sexy enough that I need to continue reminding myself of the price I paid for that.

Tim: Do you issues with any of the outdated language about God, or particularly the sexist language about men and women, that exists in the old Alcoholics Anonymous literature?

Mark: I take what I can use and leave the rest. But in the particular program I go to, CMA, nobody talks about Jesus. And even God is more a concept of “you don't know everything.” As gay men, we've adapted the program in a way that works for us. I can pick apart the language all day if I want to, but I get the same feeling in a CMA meeting thta I once got when I facilitated a support group for people with AIDS in 1986—a sense of community. It's the same feeling I got as a kid in Christian youth camp where we'd hold hands and sing a song together. You get this prickly feeling in the back of your neck that says “There's something greater here and I belong to it.”

Winning On The Price is right

Tim: I love that—it's so true. So to pivot to something fluffier, I love your essay in the book about when you appeared on “The Price is Right” in 1981 and the camera kept cutting to your lover at the time, Charlie, who was flipping out, so excited.

I love when Bob Barker asks if a handsome young man like you has a girlfriend, and you answer “Oh, several.”

Mark: I can't tell you how many people have asked me why I didn't point to Charlie and say something. It was 1981! I wanted the segment to air and I knew it wouldn't if I outed us. So I decided to play the bright-eyed, cute redneck and not rock the boat. But the funny thing is, my friend Charles, who was sitting beside Charlie, saw [the show's announcer] Johnny Olson tap the cameraman on the shoulder and point at Charlie [as though to say “Feature him.”]

Tim: You are funny in the essay about your and Charlie's matching 1981 gay clone looks—Levi's 501 button-up jeans, red T-shirts, blow-dried hair and moustaches. As the '80s progressed and you moved from New Orleans to L.A., how did your look change?

Mark: My jeans became Calvins and I wore short-collar shirts instead of wide-collar ones.

But I held on pretty stubbornly to jeans and tank tops. And after I got over my initial decade of AIDS after being diagnosed in 1985, I went from skinny twink in my twenties to muscle circuit boy in my thirties. Steroids and trainers and dancing on boxes in clubs. I was ready for the party!

Tim: I loved your essay “Once, When We Were Heroes,” when you talk about going from the intense crisis and activism and service of the worst AIDS years of the 1980s and 90s to, in middle age, a more normal life that includes brunch instead of memorial services and protests. You write, “The trauma that once consumed me is now shrouded in the fog of a fading dream.” And more than once in the essays you call out older gay men or AIDS survivors for shaming younger gay men for being more sexually carefree, especially in the PrEP era. You write about “our morbid fascination with aggressively foisting upon them the horrors we endured, as if clubbing them with fear will somehow make them rethink their youthful transgressions.”

Mark: I do marvel about how much life has changed. If it weren't for the work I do, there would be many days in a row where it would never cross my mind what happened—the deaths, the dying, the memorials. It was a long time ago and we've lived many lives since then. But I'm still reminded. Things may seem footloose and fancy-free on the apps now, but it's still in the context of making sure you're undetectable if you're poz and on PrEP if you're not. Imagine the '70s when I came of age—those hoops to jump through didn't exist.

It was wall-to-wall sexual abandon—I'd suggest more so than today. I think that gay marriage and all these advances we've made have made us overall less promiscuous, because in the '70s, that was our only vocabulary, that putting Tab A into Slot B was all we had in common.

Tim: Go on…

Mark: Today we make choices about who to sleep with based on more than “he wants to.” Maybe it was my own lack of self-esteem, but I spent most of my youth having sex with whomever said yes. Because I was raised at a time when it was not okay [to have gay sex]. So to find someone else who said it was okay was all I needed. Now we require a little more vetting.

Tim: You mean now you require a little more vetting.

Mark: You're right. But we were driven by self-loathing. I don't know, maybe being young and horny today means exactly the same thing that it did in 1978.

Tim: Have you ever thought about what would've happened with the gay community if AIDS hadn't happened?

Mark: I think about it a lot. The riddle is, did AIDS humanize us even if it set us up as tragic victims that people could feel sorry for? Or did it simply underscore that we were forlorn and damned by God?

Tim: I think it did a third thing, which is that it forced us as a community, in our desperation and anger, to assert ourselves as full human beings on the public stage. We demanded to be seen as fully human, in all our rage and grief and survivorship.

Mark: Yeah, it jolted us out of our complacency, but it's not like things were going great.

Tim: In many ways I would say that society was just on the brink of accepting gayness in the late 1970s, in the form of characters that had been popping up on shows like All in the Family and Soap. And of course the huge nationwide backlash from gays against Anita Bryant showed that we were capable of organizing when we got good and mad.

Mark: Yeah, I think it's possible we might've found that political mic anyway. Did AIDS inflame it? Yes. Would we have ended up in the same place eventually? I'd like to believe what Martin Luther King Jr. said about the arc of the moral universe being long but bending toward justice, but I guess we'll never know.

Tim: Your essay “The Fabulous Wizard of Poz” is a very funnily self-lacerating essay about how insufferably diva-like you became when you were on the cover of Poz in 2013.

It's not the first essay in the book when you take yourself to task for your narcissism. Are you really narcissistic?

Mark: I think I've either achieved a level of fame that satisfies me, so I don't have to be that way anymore, or I've matured and mellowed. But you're talking to a frustrated actor who muscled his way onto “The Price is Right” and who's been performing for crowds since I stood in front of my family and made them laugh. I was looking for a spotlight. At a certain point in my life I said, “I guess I'll be on TV because I have HIV—oh well, works for me!” Have I done it because I love the spotlight? Yes. But also I think in the service of something good. I'm able to be a silly show-off but in the service of showing joy and humanity for all of us living with HIV.

Tim: More broadly, you are very self-recriminating in the essays, about many things. It's really a through-line. Am I the first person to tell you that?

Mark: No. I think we all have a lot of of regrets—I've just written mine down. But in terms of overly criticizing myself for what might've been youthful indiscretions, I'm better about that now. I love myself. I hopefully have come to a place where I feel I deserve whatever love or success comes my way. But I will always be— [pause] It's that Imposter Syndrome. I want to criticize myself before you can do it.

I'll tell you a story. In junior high school, I was running for student body president. And at the event where you give a speech in front of the whole school, I was sitting beside a friend named Pam, the campaign manager of the other guy, and she was very nervous. I said to her, “Don't worry, you're gonna be great.” And she gets up and says, “First, I wanna say something about Mark King. He only does things for himself. He's only a leader because it brings attention to him.”

Tim: Oh my God, what a—!

Mark: I was in such shock! I didn't know what to say. So when she sits back down near me, I said, “See, that went great.” I'll never forget that moment, which told me, if you put yourself out there, they're going to think you're selfish. And part of what she said was true. So when you ask me why I'm so self-recriminating, it's because Pam told the truth 50 years ago.

Tim: Do you ever get sick of being a professional person living with HIV?

Mark: No. You would think I would by now. But there's always so much more to say. HIV is tragic but it's also fascinating. It gets us talking about religion, sex, racism, gender identity—all this stuff is wrapped up in this tiny little viral particle. People like you and me will be writing on this topic for the rest of our lives. So I feel lucky I'm enmeshed in that topic.

Tim: You're right. Many of my closest friends, especially those who are not other gay men, are people I've met in the HIV/AIDS space whom I'd never have met otherwise. So, Mark, in the book you have an essay about having a 30-year-old boyfriend when you were 15. It reminded me of many other gay men telling me similar stories, about losing their virginity to men over the age of consent when they were under it, hence making it statutory rape. But in many instances the men tell me that they really wanted the experience, that in many cases they initiated it, and they have no regrets or resentments at that person. What about you?

Mark: In that piece, I'm talking about being in the car with him right after we'd had sex and he stops the car and starts crying, and I can't figure out why. Only now when I look back do I realize that he was filled with remorse. You can see in that piece, which I wrote years ago, how confused I was about how I was supposed to feel about the affair as an adult.

Tim: How do you feel about it now?

Mark: Badly for him, that he felt such remorse. I kind of see it as my fault. People will say, “But you didn't orchestrate it—he did!” Okay, maybe that's true, but I was the one who said to him, “Oh, Jim, can we stop by your house so I can borrow your bathing suit for that pool party?” And then when we got there I was putting on a show for him trying on different suits.

Tim: You conniving little slut! (laughs)

Mark: I knew what the fuck I was doing. Now, did I understand the consequences? The power differential? No. I was trying to get laid and hoping he would do something with me. Now that's immature.

Tim: Of course the age of consent varies among the states between 16 and 18. Do you think it should be lower?

Mark: Yes. There's such a thing as assault, but that should be based on circumstance, not age. I'm not willing to go there completely in terms of people who are truly young. I'm just saying that in my circumstance, I was already a sexually active teenager and I was trying to have more sex. When my parents found out, when I was 16, that I was seeing someone who was 23, they could've put him in jail.

Tim: Was that how they found out you were gay?

Mark: Yes. My dad, the military guy, was unhappy for a couple of days but got over it. My mom held on to it—maybe because I already had an older brother living in New York who was already openly gay.

Tim: Your mom was probably like, “There goes my chance of having any grandchildren.”

Mark: Fortunately she had four other kids, so she was fine. But I remember asking her, “Why do you have such a problem with this? Dick [his brother] is gay.” And she said, “Dick is an adult who can make his own decisions. But I want you to have an easy and happy life and this will make it the opposite.”

Tim: Why do you feel like there is a disconnect between many older gay men who have a kind of laissez-faire attitude about having had sex with older men when they were teens, but younger people seem absolutely obsessed with these issues of power and consent?

Mark: I don't know. Maybe we've learned about the seminal, as it were, nature of sexuality and how it can screw us up early on. But speaking of disconnects, why do we think that underage sex is bad but we all have this daddy fixation? “Fuck me, Daddy.” I'm in full-on daddy bloom right now if you go by the unsolicited come-ons I get on Facebook every day.

Tim: As a 54-year-old, I have such mixed feelings about the daddy thing. I can get very into that daddy energy when I'm with a younger guy, and seeing how he gets off on it is very sexy, but when someone on Scruff—which I deleted recently, to the great benefit of my mental health—leads with “Hi Daddy,” I'm often turned off and find it annoying, as though I were to lead with a Latin guy by saying “Hola, papi.” It just seems obnoxious and presumptuous, like you're expecting someone you don't even know yet to play a role for you. What about you?

Mark: You can objectify me any way you want. I mean, come on—I'm 62 and doing my best here. Gay men are great at rebranding things.

Tim: Right? We can rebrand obesity as being bears.

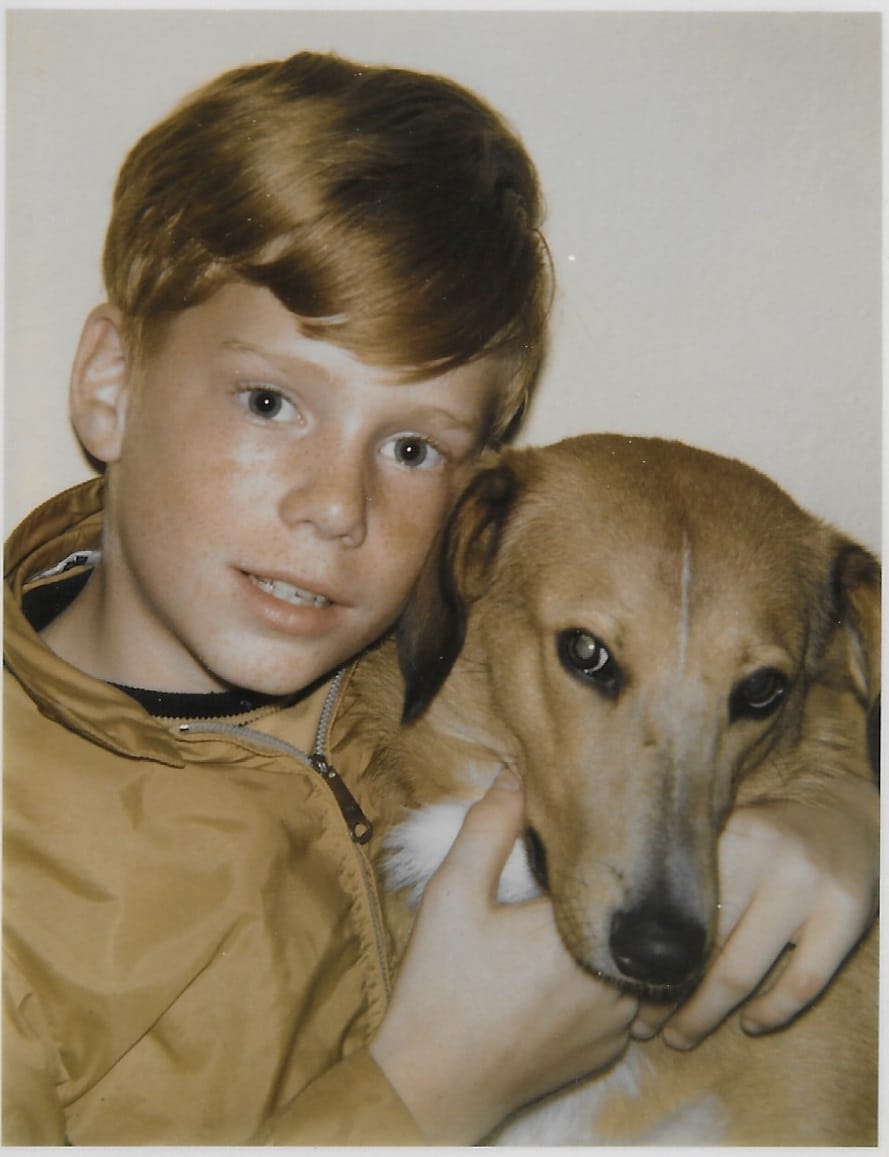

Mark: Right. Gingers only became hot like 10 or 20 years ago. Where were you when I was a red-headed 30-year-old? So now I'm a “ginger daddy.” Check, check. Listen, as for bears, if it makes us see a body type in a new way that celebrates it, then what the hell is wrong with that?

Tim: So on a related topic, in a 2013 essay, you said that you were a total top. Still?

Mark: Yes! It's so easy—it's the lazy man's way! I just show up, whereas my husband has some mysterious procedure that lasts up to two days before the appointed hour. I don't have to be the one worrying and saying, “No! Stop! Wait—am I okay?”

Tim: Is there anything about bottoming that you miss?

Mark: No.

Tim: Because you never had a period of loving being a bottom?

Mark: I was just never very good at it.

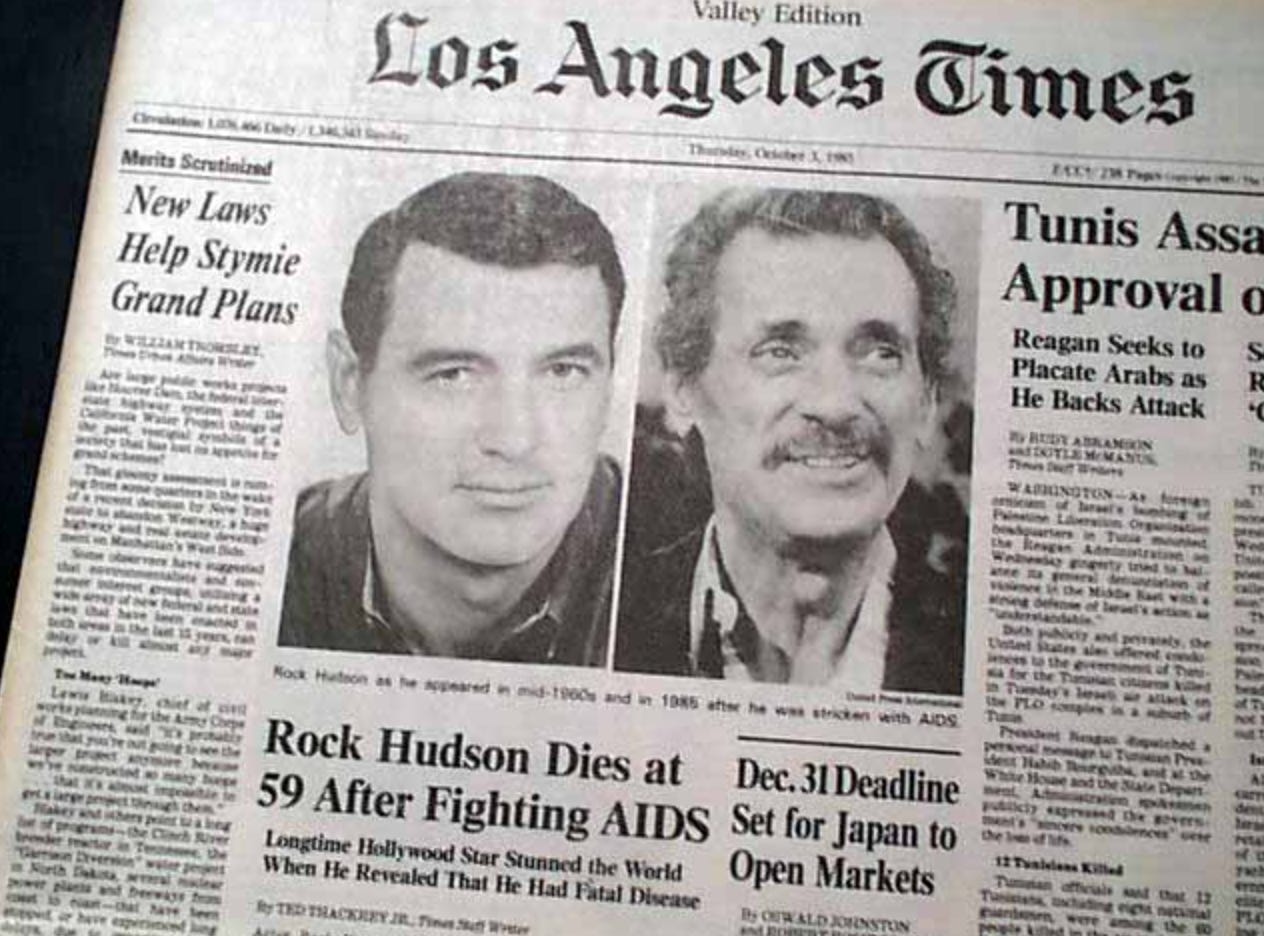

Tim: But, to segue, you were fucked by Rock Hudson in 1982, as you relate in an essay in the book.

It was interesting to read because I'd just watched the new documentary about him, All That Heaven Allowed.

Other than marveling at how supernaturally gorgeous he was, I also marveled at how, despite the tabloid rumors of the time, he was able to have this wild gay sexual and social life and no paparazzo with a zoom lens ever leaked photos of his infamous hottie pool parties. And I think you captured something in the essay, which was, beneath his affability and prodigious hooking up, this kind of exhaustion and emptiness.

Tim Murphy's books Tim Murphy's booksMark: To this day, he had one of the five largest penises I've ever seen. Someone says that in the doc—that it was a dick of historic proportions. I think he was happy to regale us with all his sexual stories, which he'd probably told a thousand times, and then he indulged himself again with this cute strawberry blond. But ultimately it was another exercise he'd gone through countless times, just sex, it meant nothing and it was time to go home.

Tim: Do you remember your feelings as he wrapped things up rather coldly?

Mark: Only when I was writing about it did I remember that world-weariness in his face. But then of course I was like, “Who's still awake that I can call?” I called my mom and dad the next day. Of course I just told them that we'd had drinks and played Trivial Pursuit—not the full story. But he was the first person I knew I'd had sex with who got sick. I was diagnosed with HIV in 1985, the same year he died.

And by no means do I mean to suggest that he gave me HIV. I'd been having sex with a lot of people.

Tim: Mark, there are so many other good, witty, thoughtful, juicy, moving essays in the book—I hope people buy and read it. One of the essays is called “Asking For What You Want.” So I'm going to wrap up by asking you: what do you most want for the rest of your life?

Mark: I want to love other people unselfishly. The most corny things they tell you about life are absolutely true, and one of them is to help somebody else along the road of this scary thing we call existence. I care about Michael's happiness as much as my own, sometimes more. I try to make sure that my work and my writing lift other people up, especially if they need it. I'm happy to do it. The most unselfish person I've ever met is Sean Strub—that guy has lifted up and helped amplify the work of other people more than anyone I've ever met.

Tim: It's true, Sean is a real class act. But what more with your life would you like to do?

Mark: I think about that a lot. What I'm doing is so fascinating and feeds me and I know I'm good at it. I want to keep doing it. It's not like I want to go conquer the movies. Twenty years from now, I'll be, like, “Help me Obi-Wan Kenobi, you're my only hope.” What's that thing called?

Tim: You mean a hologram, like how Princess Leia appears in Star Wars when she says that?

Mark: A hologram! Yes, in 20 years, I'll be a hologram talking about what it was like to live with HIV. I'll be doing the same thing I'm doing now except I'll be 80 years old and there'll be more story to tell. Whatever they learn from me is going to help the next generation. That's good enough for me. •

It's a twisty tale about four high school friends who reunite 25 years later to track down an influential but problematic teacher from their 1980s adolescence. If you do read and like it, would you be so kind as to post about it on social if you're on social, and/or rate and review it on Goodreads? Those things really help to keep a new book alive out there. And if you haven't bought it, would you consider doing so? In the woman-dominated literary/book-club fiction market, books by gay men (especially “of a certain age”) have an uphill battle and need a special boost from behind!

So thank you for that!

Other Caftan Chronicles

Jim J. Bullock's Shame Got Too Close For Comfort. Then Things Got Better

Porn Kingpin Michael Lucas Doesn't Seem Very Excited About Porn Anymore

All Drag/Porn Queen Chi Chi LaRue Ever Wanted Was to Be Popular

She got it in spades—and she's not about to let it go over a 2020 sexual assault allegation.

“Emerald City TV” Is a Stunning Time Machine Back to 1970s NYC Gay Life

Charles King's Life of Ministry, Activism and Sexy Walks in the Garden with Jesus

MAY 31 •

You Know Greg Louganis. Now Meet His Shadow Child, Oscar.

NOV 8, 2022 •