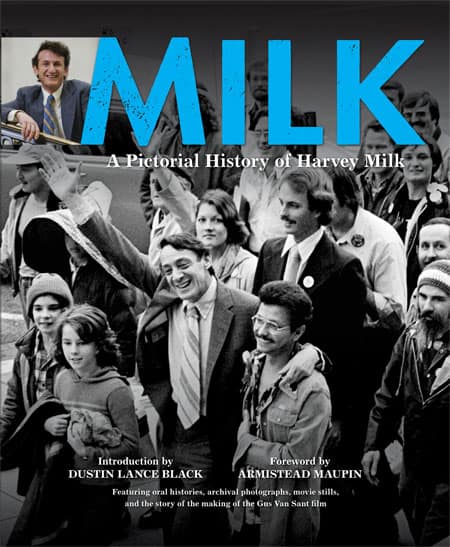

We couldn't be more pleased to feature twoexcerpts from the just published MILK: A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF HARVEY MILK.Tomorrow, one by Milk screenwriter and Oscar nominee Lance Black.But first, author Armistead Maupin offers not just another look atHarvey Milk, but also another man. Maupin is, of course, best know forhis Tales of the City.

It's not hard to imagine the joke Harvey Milk might have made about being the subject of an “oral history.” He was a bawdy and unembarrassed guy—“sex-positive,” as we now so tiresomely call it—so he never missed a chance to send up his own libido; he was part satyr, part Catskill comic, and both instincts energized his political career.

I can't say that I knew Harvey well, but we were brothers in the same revolution. In the late 70s while he was campaigning for supervisor in the Castro, I was across town on Russian Hill cranking out “Tales of the City” for the San Francisco Chronicle. Since both efforts were predicated on the then-radical notion that queers deserved a voice in the culture, Harvey and I often found ourselves on the same bill, headlining events that ran the gamut from pride marches to “No on 6” fundraisers to jockstrap auctions at the Stud. We had come of age in a time when homosexuality was not only a mental disease but a criminal offense, so to be oneself and make lemonade from such long-forbidden fruit was exhilarating beyond belief.

I can't say that I knew Harvey well, but we were brothers in the same revolution. In the late 70s while he was campaigning for supervisor in the Castro, I was across town on Russian Hill cranking out “Tales of the City” for the San Francisco Chronicle. Since both efforts were predicated on the then-radical notion that queers deserved a voice in the culture, Harvey and I often found ourselves on the same bill, headlining events that ran the gamut from pride marches to “No on 6” fundraisers to jockstrap auctions at the Stud. We had come of age in a time when homosexuality was not only a mental disease but a criminal offense, so to be oneself and make lemonade from such long-forbidden fruit was exhilarating beyond belief.

Ridiculous as it seems to me now, Harvey and I had both been naval officers and Goldwater Republicans. Like so many gay folks who defected to San Francisco in the early 70s, we'd finally had enough of the shame and secrecy that had stifled our hearts to the point of implosion. Now we were catching up on everything we'd missed, the full fireworks of adolescence: the free-range sex and clumsy puppy love and the simple, giddy freedom of standing-on-the-corner-watching-all-the-boys-go-by.

Harvey was fond of saying that he never considered himself a candidate, that the gay movement itself was the candidate. I'm not sure he believed that completely—look at him on the back of that convertible—but it does show how brilliantly he understood the nature of the army he'd assembled. This really was about us: the clerk at Macy's, the dyke cop on Valencia, that old tranny singing torch songs in the Tenderloin. It was a movement born of our long frustration and the comforting interconnectedness of everyone who had chosen that moment in history to tell the truth; it was born of a love that could finally speak its name.

Let me tell you a story.

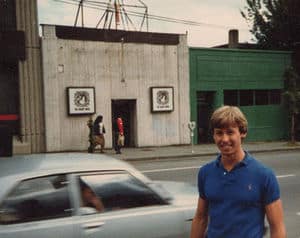

In the last month of his life, Harvey Milk met a cute twenty-five-year-old named Steve Beery at the Beaux Arts Ball in San Francisco.

Continued, AFTER THE JUMP…

BELOW: Harvey Milk on the steps of San Francisco City Hall at his swearing-in ceremony.This scene is depicted in the movie. Just as Harvey was getting ready to be sworn in, and it started to rain, he said, "A few weeks ago, Anita Bryant blamed the drought in Northern California on the gays. Who's she going to blame the rain on?" (c) Jerry Pritikin 1978

Steve was dressed as Robin from the “Batman” comics, so the supervisor introduced himself by tossing out an effectively hokey line—“Hop on my back, Boy Wonder, and I'll fly you to Gotham City.” On their first date Harvey asked Steve if he was happy being gay, because Harvey, always on the run, wondered exactly how much on-the-job training would be required. Steve took this to mean that Harvey saw him as serious boyfriend material.

I can't say for sure how many times they got together—half a dozen at the most. On the mornings when Harvey slept over, he would drive Steve to work at a credit union on Geary Boulevard and they would make out in Harvey's Volvo in full view of Steve's co-workers. Sometimes Harvey would call Steve from City Hall and playfully petition for a blow job at his desk. They had made plans to spend Thanksgiving together, but a last-minute crisis at City Hall—reports of the mass suicides at Jonestown—kept Harvey working late again. On another occasion Steve recalled Harvey shrugging off a grisly death threat that had arrived in the mail. “I can't take it seriously,” he said. “It was written with a Crayola crayon.”

I can't say for sure how many times they got together—half a dozen at the most. On the mornings when Harvey slept over, he would drive Steve to work at a credit union on Geary Boulevard and they would make out in Harvey's Volvo in full view of Steve's co-workers. Sometimes Harvey would call Steve from City Hall and playfully petition for a blow job at his desk. They had made plans to spend Thanksgiving together, but a last-minute crisis at City Hall—reports of the mass suicides at Jonestown—kept Harvey working late again. On another occasion Steve recalled Harvey shrugging off a grisly death threat that had arrived in the mail. “I can't take it seriously,” he said. “It was written with a Crayola crayon.”

Their last night together was the Friday before Harvey was murdered. Steve remembered it as a night of leisurely cuddling that turned into the gentlest sort of lovemaking. On Monday morning, Steve got the news from a coworker who'd heard it on the radio. His boss took pity on him and drove him home, where Steve found a note from his roommate saying that Harvey had called that morning with plans for getting together that evening. Numb with disbelief, Steve walked all the way across town to City Hall, where throngs of other people sobbing in the street finally made the tragedy real for him. He didn't try to push his way past the police barricades; he had come into Harvey's life too late to be part of his official history. He had just been in love with the guy.

When Steve worked up the nerve to call Harvey's office, Harvey's aide, Anne Kronenberg, arranged for him to attend the memorial service at the Opera House. “We've been trying to reach you,” she told him. “You're one of the chief mourners.” Arriving alone at the memorial service, Steve found a seat next to mine and asked if he could take it. He was crying, so for most of the service I held the hand of this stranger. His face was blurry with grief, but I could see what Harvey must have seen: a bright, inquisitive, tender-hearted soul.For the next fifteen years Steve would be my closest friend, forging a life for himself as an activist and a writer. Like so many of the young men who marchedin Harvey's army, he never quite reached middle age, never got to pass on his wisdom. AIDS robs us of more than life; it erases a universe of collective memories and hard-earned experience.

Maybe that's why we're having to learn to kick ass all over again. The generation that knew nothing of Harvey Milk before seeing the movie that bears his name was jolted into a harsh new reality when California voters decided to strip gay people of their right to marry. To us old-timers the argument for Proposition 8 was a blast from the past, a throwback to the evil theocratic Save-the-Children bullshit that Anita Bryant was spewing over thirty years ago. Why, then, was our response so maddeningly weak-kneed and closeted? Why didn't you see images of gay people in any of our ads—or even the word “gay,” for that matter? Are we that ashamed of ourselves?

The answer is no, thankfully; most of us aren't. And a growing number of young people have lost patience with the black-tie silent-auction-A-gay complacency of the organizations that claim to be fighting for our rights but don't want to ruffle feathers. These new kids are friending each other on Facebook (whatever that means) and taking to the streets on their own. My husband and I met a few of them when we picketed the Mormon temple in Oakland last month. They have love in their eyes and fire in their bellies and a commitment to finish this fight once and for all.

Harvey would have loved them.

Armistead Maupin

November 2008

San Francisco

MILK: A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF HARVEY MILK [amazon]

Excerpted from MILK: A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF HARVEY MILK, published by Newmarket Press, www.newmarketpress.comCopyright © 2009 by Armistead Maupin. All rights reserved.

Steve Beery photo courtesy of Armistead Maupin.

Photographer Jerry Pritikin has a new blog.

Special Thanks to Focus Features.