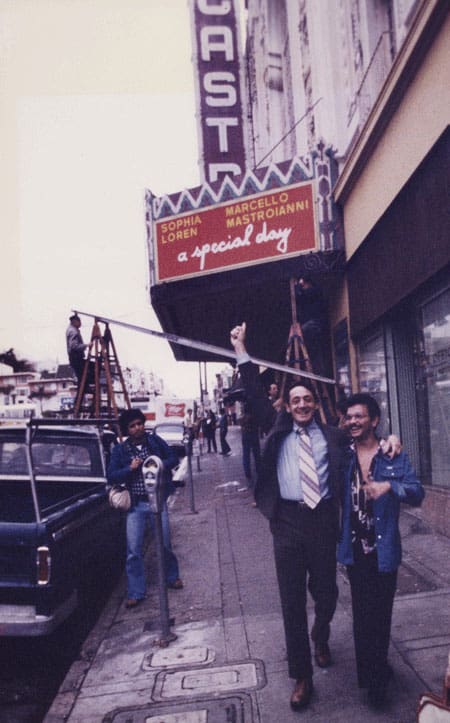

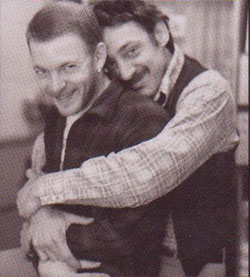

ABOVE: Harvey and Jack Lira on the day Milk was sworn in.

(c) Jerry Pritikin 1978

I hope you enjoyed yesterday's foreword by Armistead Maupin from the just published MILK: A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF HARVEY MILK. As we look forward to the Academy Awards tomorrow, we're also happy to present the first online publication of the introduction to that book by Milk screenwriter and Oscar nominee Lance Black.

30 Years Later

Dustin Lance Black

I grew up in a very conservative Mormon military household in San Antonio, Texas. I knew from the age of six what people would call me if they ever discovered my “secret.” Faggot. Deviant. Sinner. I'd heard those words ever since I can remember. I knew that I was going to Hell. I was sure God did not love me. It was clear as day that I was “less than” the other kids, and that if anyone ever found out about my little secret, beyond suffering physical harm, I would surely bring great shame to my family.

I grew up in a very conservative Mormon military household in San Antonio, Texas. I knew from the age of six what people would call me if they ever discovered my “secret.” Faggot. Deviant. Sinner. I'd heard those words ever since I can remember. I knew that I was going to Hell. I was sure God did not love me. It was clear as day that I was “less than” the other kids, and that if anyone ever found out about my little secret, beyond suffering physical harm, I would surely bring great shame to my family.

So I had two choices: to hide—to go on a Mormon mission, to get married and have a small Mormon family (eight to twelve kids)—or to do what I'd thought about many a time while daydreaming in Texas history class: take my own life. Thankfully, there weren't enough pills (fun or otherwise) inside my Mormon mother's medicine cabinet, so I pretended and I hid and I cried myself to sleep more Sabbath nights than I care to remember.

Then, when I was twelve years old, I had a turn of luck. My mom remarried a Catholic Army soldier who had orders to ship out to Fort Ord in Salinas, California. There I discovered a new family, the theater. . . and soon, San Francisco.

That's when it happened. I was almost fourteen when I heard a recording of a speech. It had been delivered on June 9, 1978, the same year my biological father had moved my family out to San Antonio. It was delivered by what I was told was an “out” gay man. His name was Harvey Milk.

"Somewhere in Des Moines or San Antonio, there is a young gay person who all of a sudden realizes that she or he is gay. Knows that if the parents find out they'll be tossed out of the house. The classmates will taunt the child and the Anita Bryants and John Briggs are doing their bit on TV, and that child has several options: staying in the closet, suicide. . . and then one day that child might open up the paper and it says, “homosexual elected in San Francisco,” and there are two new options. One option is to go to California. . . OR stay in San Antonio and fight. You've got to elect gay people so that that young child and the thousands upon thousands like that child know that there's hope for a better world. There's hope for a better tomorrow."

"Somewhere in Des Moines or San Antonio, there is a young gay person who all of a sudden realizes that she or he is gay. Knows that if the parents find out they'll be tossed out of the house. The classmates will taunt the child and the Anita Bryants and John Briggs are doing their bit on TV, and that child has several options: staying in the closet, suicide. . . and then one day that child might open up the paper and it says, “homosexual elected in San Francisco,” and there are two new options. One option is to go to California. . . OR stay in San Antonio and fight. You've got to elect gay people so that that young child and the thousands upon thousands like that child know that there's hope for a better world. There's hope for a better tomorrow."That moment when I heard Harvey for the first time . . . that was the first time I really knew someone loved me for me. From the grave, over a decade after his assassination, Harvey gave me life. . . he gave me hope.

At that very same moment, without knowing it, I became a pawn in a game of political power wrangling that is still sheddingblood from DC to Sacramento, El Paso to Altoona.

Continued, AFTER THE JUMP…

In the following years, I watched careers, political and otherwise, cut short through revelations of this or that official's sexuality. And in 2004, I looked on with horror as a President won re-election by pitting homophobes against gays and lesbians. If there had been a Harvey Milk, if there had been a movement of great hope and change, I certainly couldn't see it from where I stood four and a half years ago when I started this journey to tell Harvey's story.

In the following years, I watched careers, political and otherwise, cut short through revelations of this or that official's sexuality. And in 2004, I looked on with horror as a President won re-election by pitting homophobes against gays and lesbians. If there had been a Harvey Milk, if there had been a movement of great hope and change, I certainly couldn't see it from where I stood four and a half years ago when I started this journey to tell Harvey's story.

Thirty years after Harvey Milk was assassinated, in the summer of 2008, with antigay measures on the ballot in several states, I tuned in to the Democratic National Convention to see how his message had fared. Back in 1972, Jim Foster, an openly gay man, stood up in front of the convention and on prime-time national television said, “We do not come to you pleading your understanding or begging your tolerance, we come to you affirming our pride in our life-style, affirming the validity to seek and maintain meaningful emotional relationships and affirming our right to participate in the life of this country on an equal basis with every citizen.” What did I hear at the DNC in 2008? Almost nothing. And then there was the Republican National Convention: Sarah Palin, John McCain, flashy, divisive, patriotic speeches. And even there, not a mention of gay or lesbian people. . . bigoted or otherwise.

I left those conventions with a deep, sinking fear. They've found the surefire way to kill the gay and lesbian movement for good. They'll make us invisible. They'll make us all disappear. It's happened before. Reagan did it in the 80s with six years of silence about the AIDS crisis.

I left those conventions with a deep, sinking fear. They've found the surefire way to kill the gay and lesbian movement for good. They'll make us invisible. They'll make us all disappear. It's happened before. Reagan did it in the 80s with six years of silence about the AIDS crisis.

You see, one of the biggest hurdles for the gay community has always been invisibility. Unlike the black movement and the women's movement, gays and lesbians are not always immediately identifiable. People still go their entire careers without coming out to their co-workers, not to mention their relatives or their neighbors. Harvey Milk saw this problem, and shouted out the solution, “You must come OUT!”

The entire concept of coming out was devised and pushed for by leaders like Harvey Milk back in 1978 as a way to counter this visibility problem. If people don't know who they are hurting, they don't mind discriminating against them. Watching these two conventions, I got a sinking feeling that Milk's beloved gay and lesbian movement was off the table. I felt myself slowly vanishing, and for gay and lesbian people, invisibility equals death.

Thirty years after Harvey began his fight for GLBT (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender) equality, I am still “less than” a heterosexual when it comes to my civil rights in America. If I fall in love with someone in a foreign country, I can't marry him and bring him home. I can't be out in the military, there are inheritance rights issues, adoption rights, social security, taxation, immigration, employment, housing, and access to health care rights, social services, and education rights, and on and on. The message to gay and lesbian youth today is that they are still inferior.

Thirty years after Harvey began his fight for GLBT (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender) equality, I am still “less than” a heterosexual when it comes to my civil rights in America. If I fall in love with someone in a foreign country, I can't marry him and bring him home. I can't be out in the military, there are inheritance rights issues, adoption rights, social security, taxation, immigration, employment, housing, and access to health care rights, social services, and education rights, and on and on. The message to gay and lesbian youth today is that they are still inferior.

Today, in 2008, The Gay and Lesbian Task Force reports that a third of all gay youth attempt suicide, that gay youth are four times more likely than straights to try to take their own lives, and if a kid does survive, 26 percent are told to leave home when they come out. It's estimated that 20 to 40 percent of the 1.6 million homeless youth in America today identify as gay or lesbian. Harvey Milk's message is needed now more than ever.

So much of what I've done in this business up to this point has been to make myself ready to take on the overwhelming responsibility of retelling Harvey's story. It took many years of research, digging through archives, driving up to San Francisco in search of Harvey's old friends and foes, charging a couple of nights at the Becks motor lodge on Market and Castro with my principal source, Harvey's political protégé, Cleve Jones.

What I discovered on those trips wasn't the legend of the man that I'd heard in adolescence. What I discovered was a deeply flawed man, a man who had grown up closeted, a man who failed in business and in his relationships, a man who got a very late start. Through Harvey's friends, foes, lovers, and opponents, I met the real Harvey Milk.

What I discovered on those trips wasn't the legend of the man that I'd heard in adolescence. What I discovered was a deeply flawed man, a man who had grown up closeted, a man who failed in business and in his relationships, a man who got a very late start. Through Harvey's friends, foes, lovers, and opponents, I met the real Harvey Milk.

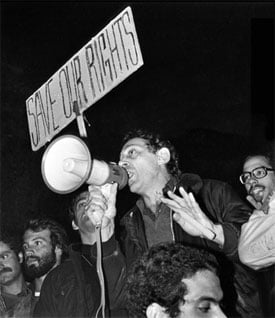

Those I interviewed also shared stories of a time in San Francisco when it seemed anything was possible. The Castro was booming. Gay and lesbian people were making headway in the battle for equal rights. And from the ashes of defeats in Florida, Kansas, and Oregon rose a big-eared, floppy-footed leader who was able to reach out to other communities, to the disenfranchised, and to unexpected allies. He convinced an entire people to “come out,” and against all odds, he fought back and won on Election Day.

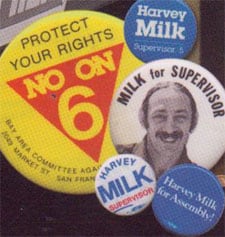

So what happened on Election Day, November 4, 2008, thirty years later? When I began this project, I could never have predicted the parallels between Proposition 8 in California in 2008 and Harvey's fight over Proposition 6 in 1978. Both statewide initiatives sought to take away gay and lesbian rights. By the early hours of November 5, though, it became clear this modern-day fight wouldn't echo Harvey's victory in 1978. Only weeks before Milk's biography would hit the big screen, Proposition 8 in California passed. It changed the state's constitution to revoke the right of marriage to gay and lesbian citizens who had already been enjoying that right. Thirty years, almost to the day, after Harvey Milk had successfully defeated Proposition 6 in California, the pendulum had swung back.

One week later, Cleve Jones and I picked up the torch of his former mentor and father figure with these words (as published in the San Francisco Chronicle):

We have loved our country even as we have been subjected to discrimination, harassment and violence at the hands of our countrymen. We have loved God, even as we were rejected and abandoned by religious leaders, our churches, synagogues and mosques. We have loved democracy, even as we witnessed the ballot box used to deny us our rights.

We have always kept faith with the American people, our neighbors,co-workers, friends and families. But today that faith is tested and we find ourselves at a crossroad in history.

Will we move forward together? Will we affirm that the American dream is alive and real? Will we finally guarantee full equality under the law for all Americans? Or will we surrender to the worst, most divisive appeals to bigotry, ignorance and fear?

I imagine Harvey would be surprised that words like these would still be needed in 2008. What went wrong? Why did the GLBT community lose a civil rights fight that Harvey could likely have won thirty years ago?

To me, the answers are clear. GLBT leaders today have been asking straight allies to stand up for the gay community instead of encouraging gay and lesbian people to proudly represent themselves. The movement has become closeted again. The movement has lost the message of Harvey Milk. Who is to blame? The philosopher George Santayana said so long ago,“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

I didn't grow up with any knowledge of GLBT heroes, but there are many. I didn't grow up with any instruction about GLBT history, but it is a rich history, filled with valuable, universal lessons. It is only in recent years that Hollywood has agreed to risk its dollars on films that depict gay protagonists, and only now, thirty years after Milk's assassination, that Hollywood has agreed to risk its dollars to depict one of the gay movement's greatest heroes.

Now, thanks to the bravery of directors like Gus Van Sant, producers like Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen, and companies like Michael London's Groundswell and Focus Features, I was given a shot at creating a popularized history that young people, GLBT leaders, and our future straight allies can look at and learn from. With this and the many other films I hope will follow, perhaps we are not doomed to keep repeating the same mistakes of our past.

Now, thanks to the bravery of directors like Gus Van Sant, producers like Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen, and companies like Michael London's Groundswell and Focus Features, I was given a shot at creating a popularized history that young people, GLBT leaders, and our future straight allies can look at and learn from. With this and the many other films I hope will follow, perhaps we are not doomed to keep repeating the same mistakes of our past.

But even in these difficult times, all is not lost. By example, Harvey taught us that from our darkest hours comes “Hope.” The night after this year's election, I attended a rally against the passage of Proposition 8, and the speakers onstage were mostly the folks who had waged the failed, closeted “No on 8” campaign. Yes, they were saying inspiring, fiery words about the injustice. Yes, there were some cheers, but mostly the mood was restless. And then something magical happened.

The young people in the crowd started to move. Perhaps it was instinct, perhaps they knew more about their own movement's history than the folks onstage, perhaps they just weren't willing to continue the current leadership's policy of closeting and good behavior. They started to move. They marched away from the stage. They started to march out of the gay ghetto of West Hollywood and up to a straight neighborhood. Within minutes a public march, eight thousand strong, had begun. It looked almost identical to Harvey's marches up Market Street in San Francisco in 1977. Young people, old people, gay people, lesbians, bisexual folks, transgender ones, and many, many straight allies marched up to Sunset Boulevard, took over the city, and started doing what Harvey had talked about. They started giving a face to GLBT people again. They showed the world who was hurt at the ballot box the night before. They came out. They weren't asking straight people to advocate for their rights. In their chants and on their signs, they demanded equality themselves.

In 1977, Harvey Milk claimed Anita Bryant didn't win in Dade County when she overturned all of their gay rights laws. He claimed that the defeat in Florida had brought his people together. It seemed the same thing had happened thirty years later.

And yes, those demonstrators on television, and Harvey's message in theaters, are exceedingly important in the continued fight over Proposition 8, but they are important to me for another, more personal reason. . . because I feel certain there is another kid out there in San Antonio tonight who woke up on November 5, 2008, and heard that gay people had lost their rights in California, that they were still “less than,” and I know all too well the dire solutions that may have flashed through his or her head.

And yes, those demonstrators on television, and Harvey's message in theaters, are exceedingly important in the continued fight over Proposition 8, but they are important to me for another, more personal reason. . . because I feel certain there is another kid out there in San Antonio tonight who woke up on November 5, 2008, and heard that gay people had lost their rights in California, that they were still “less than,” and I know all too well the dire solutions that may have flashed through his or her head.

Those demonstrators on television sets all across the country aren't just making a statement against the bigotry of Prop 8; they are sending a message of hope to that child in San Antonio: “You are not less than,” “You have brothers and sisters and friends, thousands of them,” “There is hope for a better tomorrow,” and like Harvey said, “You can come to California. . . or you can stay in San Antonio and FIGHT.”

These photos and the accompanying quotes from my research interviews in this book don't tell the story of a man born to lead, but of a regular man with many flaws who did what many others wouldn't . . . he did what his people need to do again today, thirty years later . . . Harvey Milk stood up and fought back.

Dustin Lance Black

November 2008

Los Angeles

MILK: A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF HARVEY MILK [amazon]

Excerpted from MILK: A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF HARVEY MILK, published by Newmarket Press, www.newmarketpress.com Copyright © 2009 by Dustin Lance Black. All rights reserved

Photographer Jerry Pritikin has a new blog.

Special Thanks to Focus Features.