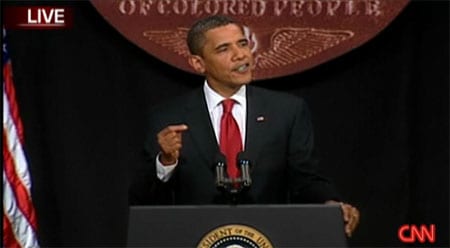

President Obama addressed the NAACP at its Centennial Convention this evening in New York. In a speech mentioning the economy, health care, education and HIV/AIDS, he also addressed the issue of discrimination, calling for an end to prejudice against minority groups, specifically African-American women, Latinos, Muslim Americans, and gays and lesbians.

Said Obama: "The first thing we need to do is make real the words of your charter and eradicate prejudice, bigotry, and discrimination among citizens of the United States. I understand there may be a temptation among some to think that discrimination is no longer a problem in 2009. And I believe that overall, there probably has never been less discrimination in America than there is today. But make no mistake: the pain of discrimination is still felt in America. By African-American women paid less for doing the same work as colleagues of a different color and a different gender. By Latinos made to feel unwelcome in their own country. By Muslim Americans viewed with suspicion simply because they kneel down to pray to their God. By our gay brothers and sisters, still taunted, still attacked, still denied their rights. On the 45th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, discrimination must not stand. Not on account of color or gender; how you worship or who you love. Prejudice has no place in the United States of America."

Video and full remarks (as prepared for delivery), AFTER THE JUMP…

***Remarks of President Barack Obama – NAACP Centennial***

It is an honor to be here, in the city where the NAACP was formed, to mark its centennial. What we celebrate tonight is not simply the journey the NAACP has traveled, but the journey that we, as Americans, have traveled over the past one hundred years.

It is a journey that takes us back to a time before most of us were born, long before the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act, and Brown v. Board of Education; back to an America just a generation past slavery. It was a time when Jim Crow was a way of life; when lynchings were all too common; and when race riots were shaking cities across a segregated land.

It was in this America where an Atlanta scholar named W.E.B. Du Bois, a man of towering intellect and a fierce passion for justice, sparked what became known as the Niagara movement; where reformers united, not by color but cause; and where an association was born that would, as its charter says, promote equality and eradicate prejudice among citizens of the United States.

From the beginning, Du Bois understood how change would come – just as King and all the civil rights giants did later. They understood that unjust laws needed to be overturned; that legislation needed to be passed; and that Presidents needed to be pressured into action. They knew that the stain of slavery and the sin of segregation had to be lifted in the courtroom and in the legislature.

But they also knew that here, in America, change would have to come from the people. It would come from people protesting lynching, rallying against violence, and walking instead of taking the bus. It would come from men and women – of every age and faith, race and region – taking Greyhounds on Freedom Rides; taking seats at Greensboro lunch counters; and registering voters in rural Mississippi, knowing they would be harassed, knowing they would be beaten, knowing that they might never return.

Because of what they did, we are a more perfect union. Because Jim Crow laws were overturned, black CEOs today run Fortune 500 companies. Because civil rights laws were passed, black mayors, governors, and Members of Congress serve in places where they might once have been unable to vote. And because ordinary people made the civil rights movement their own, I made a trip to Springfield a couple years ago – where Lincoln once lived, and race riots once raged – and began the journey that has led me here tonight as the 44th President of the United States of America.

And yet, even as we celebrate the remarkable achievements of the past one hundred years; even as we inherit extraordinary progress that cannot be denied; even as we marvel at the courage and determination of so many plain folks – we know that too many barriers still remain.

We know that even as our economic crisis batters Americans of all races, African Americans are out of work more than just about anyone else – a gap that's widening here in New York City, as detailed in a report this week by Comptroller Bill Thompson.

We know that even as spiraling health care costs crush families of all races, African Americans are more likely to suffer from a host of diseases but less likely to own health insurance than just about anyone else.

We know that even as we imprison more people of all races than any nation in the world, an African-American child is roughly five times as likely as a white child to see the inside of a jail.

And we know that even as the scourge of HIV/AIDS devastates nations abroad, particularly in Africa, it is devastating the African-American community here at home with disproportionate force.

These are some of the barriers of our time. They're very different from the barriers faced by earlier generations. They're very different from the ones faced when fire hoses and dogs were being turned on young marchers; when Charles Hamilton Houston and a group of young Howard lawyers were dismantling segregation.

But what is required to overcome today's barriers is the same as was needed then. The same commitment. The same sense of urgency. The same sense of sacrifice. The same willingness to do our part for ourselves and one another that has always defined America at its best.

The question, then, is where do we direct our efforts? What steps do we take to overcome these barriers? How do we move forward in the next one hundred years?

The first thing we need to do is make real the words of your charter and eradicate prejudice, bigotry, and discrimination among citizens of the United States. I understand there may be a temptation among some to think that discrimination is no longer a problem in 2009. And I believe that overall, there's probably never been less discrimination in America than there is today.

But make no mistake: the pain of discrimination is still felt in America. By African-American women paid less for doing the same work as colleagues of a different color and gender. By Latinos made to feel unwelcome in their own country. By Muslim Americans viewed with suspicion for simply kneeling down to pray. By our gay brothers and sisters, still taunted, still attacked, still denied their rights.

On the 45th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, discrimination must not stand. Not on account of color or gender; how you worship or who you love. Prejudice has no place in the United States of America.

But we also know that prejudice and discrimination are not even the steepest barriers to opportunity today. The most difficult barriers include structural inequalities that our nation's legacy of discrimination has left behind; inequalities still plaguing too many communities and too often the object of national neglect.

These are barriers we are beginning to tear down by rewarding work with an expanded tax credit; making housing more affordable; and giving ex-offenders a second chance. These are barriers that we are targeting through our White House Office on Urban Affairs, and through Promise Neighborhoods that build on Geoffrey Canada's success with the Harlem Children's Zone; and that foster a comprehensive approach to ending poverty by putting all children on a pathway to college, and giving them the schooling and support to get there.

But our task of reducing these structural inequalities has been made more difficult by the state, and structure, of the broader economy; an economy fueled by a cycle of boom and bust; an economy built not on a rock, but sand. That is why my administration is working so hard not only to create and save jobs in the short-term, not only to extend unemployment insurance and help for people who have lost their health care, not only to stem this immediate economic crisis, but to lay a new foundation for growth and prosperity that will put opportunity within reach not just for African Americans, but for all Americans.

One pillar of this new foundation is health insurance reform that cuts costs, makes quality health coverage affordable for all, and closes health care disparities in the process. Another pillar is energy reform that makes clean energy profitable, freeing America from the grip of foreign oil, putting people to work upgrading low-income homes, and creating jobs that cannot be outsourced. And another pillar is financial reform with consumer protections to crack down on mortgage fraud and stop predatory lenders from targeting our poor communities.

All these things will make America stronger and more competitive. They will drive innovation, create jobs, and provide families more security. Still, even if we do it all, the African-American community will fall behind in the United States and the United States will fall behind in the world unless we do a far better job than we have been doing of educating our sons and daughters. In the 21st century – when so many jobs will require a bachelor's degree or more, when countries that out-educate us today will outcompete us tomorrow – a world-class education is a prerequisite for success.

You know what I'm talking about. There's a reason the story of the civil rights movement was written in our schools. There's a reason Thurgood Marshall took up the cause of Linda Brown. There's a reason the Little Rock Nine defied a governor and a mob. It's because there is no stronger weapon against inequality and no better path to opportunity than an education that can unlock a child's God-given potential.

Yet, more than a half century after Brown v. Board of Education, the dream of a world-class education is still being deferred all across this country. African-American students are lagging behind white classmates in reading and math – an achievement gap that is growing in states that once led the way on civil rights. Over half of all African-American students are dropping out of school in some places. There are overcrowded classrooms, crumbling schools, and corridors of shame in America filled with poor children – black, brown, and white alike.

The state of our schools is not an African-American problem; it's an American problem. And if Al Sharpton, Mike Bloomberg, and Newt Gingrich can agree that we need to solve it, then all of us can agree on that. All of us can agree that we need to offer every child in this country the best education the world has to offer from the cradle through a career.

That is our responsibility as the United States of America. And we, all of us in government, are working to do our part by not only offering more resources, but demanding more reform.

When it comes to higher education, we are making college and advanced training more affordable, and strengthening community colleges that are a gateway to so many with an initiative that will prepare students not only to earn a degree but find a job when they graduate; an initiative that will help us meet the goal I have set of leading the world in college degrees by 2020.

We are creating a Race to the Top Fund that will reward states and public school districts that adopt 21st century standards and assessments. And we are creating incentives for states to promote excellent teachers and replace bad ones – because the job of a teacher is too important for us to accept anything but the best.

We should also explore innovative approaches being pursued here in New York City; innovations like Bard High School Early College and Medgar Evers College Preparatory School that are challenging students to complete high school and earn a free associate's degree or college credit in just four years.

And we should raise the bar when it comes to early learning programs. Today, some early learning programs are excellent. Some are mediocre. And some are wasting what studies show are – by far – a child's most formative years.

That's why I have issued a challenge to America's governors: if you match the success of states like Pennsylvania and develop an effective model for early learning; if you focus reform on standards and results in early learning programs; if you demonstrate how you will prepare the lowest income children to meet the highest standards of success – you can compete for an Early Learning Challenge Grant that will help prepare all our children to enter kindergarten ready to learn.

So, these are some of the laws we are passing. These are some of the policies we are enacting. These are some of the ways we are doing our part in government to overcome the inequities, injustices, and barriers that exist in our country.

But all these innovative programs and expanded opportunities will not, in and of themselves, make a difference if each of us, as parents and as community leaders, fail to do our part by encouraging excellence in our children. Government programs alone won't get our children to the Promised Land. We need a new mindset, a new set of attitudes – because one of the most durable and destructive legacies of discrimination is the way that we have internalized a sense of limitation; how so many in our community have come to expect so little of ourselves.

We have to say to our children, Yes, if you're African American, the odds of growing up amid crime and gangs are higher. Yes, if you live in a poor neighborhood, you will face challenges that someone in a wealthy suburb does not. But that's not a reason to get bad grades, that's not a reason to cut class, that's not a reason to give up on your education and drop out of school. No one has written your destiny for you. Your destiny is in your hands – and don't you forget that.

To parents, we can't tell our kids to do well in school and fail to support them when they get home. For our kids to excel, we must accept our own responsibilities. That means putting away the Xbox and putting our kids to bed at a reasonable hour. It means attending those parent-teacher conferences, reading to our kids, and helping them with their homework.

And it means we need to be there for our neighbor's son or daughter, and return to the day when we parents let each other know if we saw a child acting up. That's the meaning of community. That's how we can reclaim the strength, the determination, the hopefulness that helped us come as far as we already have.

It also means pushing our kids to set their sights higher. They might think they've got a pretty good jump shot or a pretty good flow, but our kids can't all aspire to be the next LeBron or Lil Wayne. I want them aspiring to be scientists and engineers, doctors and teachers, not just ballers and rappers. I want them aspiring to be a Supreme Court Justice. I want them aspiring to be President of the United States.

So, yes, government must be a force for opportunity. Yes, government must be a force for equality. But ultimately, if we are to be true to our past, then we also have to seize our own destiny, each and every day.

That is what the NAACP is all about. The NAACP was not founded in search of a handout. The NAACP was not founded in search of favors. The NAACP was founded on a firm notion of justice; to cash the promissory note of America that says all our children, all God's children, deserve a fair chance in the race of life.

It is a simple dream, and yet one that has been denied – one still being denied – to so many Americans. It's a painful thing, seeing that dream denied. I remember visiting a Chicago school in a rough neighborhood as a community organizer, and thinking how remarkable it was that all of these children seemed so full of hope, despite being born into poverty, despite being delivered into addiction, despite all the obstacles they were already facing.

And I remember the principal of the school telling me that soon all of that would begin to change; that soon, the laughter in their eyes would begin to fade; that soon, something would shut off inside, as it sunk in that their hopes would not come to pass – not because they weren't smart enough, not because they weren't talented enough, but because, by accident of birth, they didn't have a fair chance in life.

So, I know what can happen to a child who doesn't have that chance. But I also know what can happen to a child who does. I was raised by a single mother. I don't come from a lot of wealth. I got into my share of trouble as a kid. My life could easily have taken a turn for the worse. But that mother of mine gave me love; she pushed me, and cared about my education; she took no lip and taught me right from wrong. Because of her, I had a chance to make the most of my abilities. I had the chance to make the most of my opportunities. I had the chance to make the most of life.

The same story holds for Michelle. The same story holds for so many of you. And I want all the other Barack Obamas out there, and all the other Michelle Obamas out there, to have that same chance – the chance that my mother gave me; that my education gave me; that the United States of America gave me. That is how our union will be perfected and our economy rebuilt. That is how America will move forward in the next one hundred years.

And we will move forward. This I know – for I know how far we have come. Last week, in Ghana, Michelle and I took Malia and Sasha to Cape Coast Castle, where captives were once imprisoned before being auctioned; where, across an ocean, so much of the African-American experience began. There, reflecting on the dungeon beneath the castle church, I was reminded of all the pain and all the hardships, all the injustices and all the indignities on the voyage from slavery to freedom.

But I was also reminded of something else. I was reminded that no matter how bitter the rod or how stony the road, we have persevered. We have not faltered, nor have we grown weary. As Americans, we have demanded, strived for, and shaped a better destiny.

That is what we are called to do once more. It will not be easy. It will take time. Doubts may rise and hopes recede.

But if John Lewis could brave Billy clubs to cross a bridge, then I know young people today can do their part to lift up our communities.

If Emmet Till's uncle Mose Wright could summon the courage to testify against the men who killed his nephew, I know we can be better fathers and brothers, mothers and sisters in our own families.

If three civil rights workers in Mississippi – black and white, Christian and Jew, city-born and country-bred – could lay down their lives in freedom's cause, I know we can come together to face down the challenges of our own time. We can fix our schools, heal our sick, and rescue our youth from violence and despair.

One hundred years from now, on the 200th anniversary of the NAACP, let it be said that this generation did its part; that we too ran the race; that full of the faith that our dark past has taught us, full of the hope that the present has brought us, we faced, in our own lives and all across this nation, the rising sun of a new day begun. Thank you, God bless you, and may God bless the United States of America.