BY JASON BERRY / GlobalPost

"You don't play with children's lives!" Francis told the French advocacy group International Catholic Child Bureau.

Pope Francis has taken another bold step in his rhetoric of reform, this time remarking on the clergy abuse crisis, raising the bar of expectations on just how he plans to confront a deeply systemic crisis.

Pope Francis has taken another bold step in his rhetoric of reform, this time remarking on the clergy abuse crisis, raising the bar of expectations on just how he plans to confront a deeply systemic crisis.

According to the Vatican press office, the pope in meeting with a French advocacy group International Catholic Child Bureau made his most forceful statement yet on the scandals that have jolted the church since the 1980s: “I feel called to take responsibility for all the evil some priests — large in number, but not in proportion to the total — have committed and to ask forgiveness for the damage they've done with the sexual abuse of children."

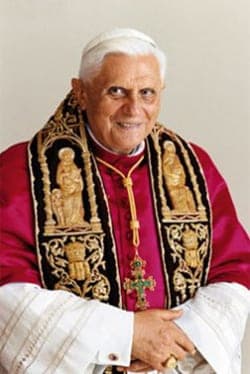

Benedict and John Paul II made apologetic statements, though neither alluded to a structural response, as Francis did today:

“We don’t want to take a step backward with this problem and with the sanctions that must be imposed,” he said.

He continued: "On the contrary, I believe we must be very strong. You don't play with children's lives!"

The precise nature of those sanctions has yet to be revealed, but the overriding problem for years has been the de facto immunity for cardinals and bishops. Under the canon law system, Vatican tribunals, many of them run by cardinals and bishops, deal with internal church affairs.

Pope Francis has sent contradictory signals about his resolve on the abuse crisis. Earlier this year, he celebrated Mass at the Vatican with Cardinal Roger Mahony of Los Angeles, whose lawyers spent years resisting subpoena attempts by the county district attorney for clergy personnel records, and to compel the cardinal to testify before a grand jury. He never did. A key concession in the archdiocese’s four-year litigation with abuse victims, which resulted in a $660 million settlement in 2007, was the release of records on the clergy sex offenders.

Although the cardinal met with many victims personally to apologize, his legal team managed to delay releasing the documents for another six years, by which time the statute of limitations had lapsed on a potential prosecution of Mahony. He allegedly used psychiatric treatment facilities as safe houses for clergy predators, many of whom were subsequently returned to pastoral work and fresh victims.

Compared with the other two major issues that Pope Francis inherited — a runway Vatican Bank stained by money laundering and a Roman Curia so balkanized that Benedict’s personal valet leaked documents to the media — the abuse crisis is a geographically sprawling challenge with different legal systems in various countries the Holy See has asked bishops to cooperate with, a reform under Benedict.

Compared with the other two major issues that Pope Francis inherited — a runway Vatican Bank stained by money laundering and a Roman Curia so balkanized that Benedict’s personal valet leaked documents to the media — the abuse crisis is a geographically sprawling challenge with different legal systems in various countries the Holy See has asked bishops to cooperate with, a reform under Benedict.

But the fraternal culture of bishops, who consider themselves a line of spiritual descendants from Jesus, has no inherent checks and balances, a factor that works against church directives for bishops to report clergy accused of sexual crimes to legal authorities.

In 2002, the American bishops met a firestorm of negative publicity ignited by the Boston Globe investigation of Cardinal Bernard Law’s recycling of sex offenders. At their summer conference that year in Dallas, the bishops adopted a youth protection charter with a “zero-tolerance” policy. They also commissioned a 12-member National Review Board of prominent lay Catholics to research the causes of the crisis and make recommendations.

When the board members met in 2003 with Cardinal Mahony in Los Angeles, he was surrounded by lawyers. “I wondered what planet he lived on,” New York attorney Pamela Hayes, a member of the NRB, told me at the time.

Other bishops resisted the board’s questions, and the reform recommendations. Nevertheless, the charter has seen many dioceses adapt “safe touch” education programs for children, and screen more carefully for teachers, lay employees and clergy involved with children.

But bishops who ignore the charter suffer no consequences.

“The church has let bishops act as if their own charter, their own baseline, if you will, has no teeth,” Illinois Supreme Court Justice Anne Burke, another NRB member, told GlobalPost.

She referenced Kansas City Bishop Robert Finn, who was convicted of a criminal misdemeanor for shielding Father Shawn Ratigan after he was caught with hundreds of pornographic photographs of young girls. Ratigan later drew a 50-year conviction sentence. Finn drew a suspended sentence.

Father James Connell, a canon lawyer in Milwaukee, has filed an appeal with the Vatican to have Finn removed.

“The bishops didn’t take any action against Finn,” said Burke. “Who polices the bishops?”

Francis recently named eight people to a special group, the Pontificial Commission for the Protection of Minors, to advise him on a reform initiative.

Marie Collins of Ireland is the one abuse survivor in the group.

"There's no point in my mind of having gold-plated child-protection programs in place if there's no sanction for a bishop who decides to ignore them," Collins recently told the AP. "The reason everyone is so angry is not because they have abusers in their ranks. Abusers are in every rank of society. It's because of the systemic cover-up."