It takes a gifted singer to sing this horribly. Every other note is wrong. No phrasing goes unmangled by shortness of breath. No lovely moment meant to soar cannot be shattered by a flat ear-piercing decibel.

The central conceit of Stephen Frears new comedy Florence Foster Jenkins is that Florence, a considerably wealthy patron of the arts played by Meryl Streep, lives for music but is ghastly at it. The inside joke, given the casting, is that we all know La Streep can sing with the best of them.

She followed the “is there nothing she can't do?” revelation of Ironweed‘s tragic showstopper “He's Me Pal” (1987, Oscar-Nominated) with transcendent country crooner feeling in Postcards From the Edge (1990, Oscar-Nominated), and just kept on singing whenever a movie gave her the opportunity all the way up through last year's Ricki and the Flash which was practically a concert film there were so many scenes of Streep at the mic, rocking out.

Florence Foster Jenkins doesn't rock out. Florence is not that kind of girl and Florence, also, is not that kind of movie.

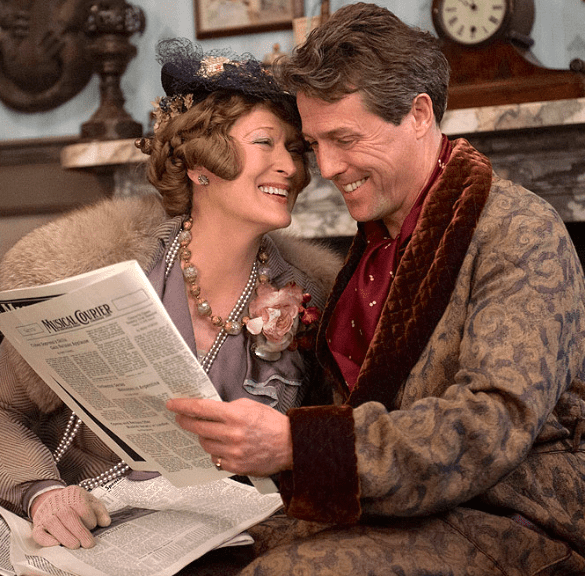

The old woman is content to host parties (potato salad is a must!) and go to bed early with a chaste tucking in from her charming husband St Claire Bayfield (Hugh Grant, the best he's been in ages) who is the rock star behind the scenes. He does all the heavy showmanship lifting to keep Florence dreamy and happy, rather than sad and sickly; for St. Claire and even for Florence, the movie argues, her ignorance is their bliss.

The old woman is content to host parties (potato salad is a must!) and go to bed early with a chaste tucking in from her charming husband St Claire Bayfield (Hugh Grant, the best he's been in ages) who is the rock star behind the scenes. He does all the heavy showmanship lifting to keep Florence dreamy and happy, rather than sad and sickly; for St. Claire and even for Florence, the movie argues, her ignorance is their bliss.

If only our ignorance was also bliss. The movie is right there with St Claire in assuming that everyone will be happier with fantasy than reality. But can't we have equal portions of both? Florence Foster Jenkins is based on a true story but it's tough to say which parts are fiction unless your expertise is eccentric American socialites of WWII era Manhattan. Much of the movie plays like it couldn't possible be true but here we are.

The movie's ignorance-is-bliss mantra extends even to the main storyline.

Florence's dream is to perform at Carnegie Hall and we're given little information as to how she moves from a high society figure to a divisive populist sensation that can sell that venue out. Frankly, the occasional peaks at harder truths like the couple's sexless open marriage and Florence's subtle manipulations (especially with her money) are so compelling that it's easy to wish the film wasn't quite so docile and satisfied within the comfort of the broadly comic.

Not that there's anything wrong with fanciful comedy. You know that Streep and Grant excel at it, and they're well supported by a lively turn from stage goddess Nina Arianda (Venus in Fur Tony winner) as the tactless new wife of one of their richest friends.

She can't believe her ears when she first hears Florence sing. Simon Helberg (The Big Bang Theory) is less successful as Florence's chosen accompanist who is essentially the third lead. He's gifted with so many closeups that you need more from the performance than awkward nervousness. That's particularly problematic when the movie throws in a very gay party but his own sexuality remains opaque or perhaps non-existent.

All told this is a rather old fashioned trifle of a star vehicle and what depth it does have comes from what can be inferred in performance rather than what the movie delivers.

That's as we've come to expect from the director Stephen Frears. Though his breakthrough came with the rather daring and sociopolitically savvy My Beautiful Laundrette (1985), he's mostly abandoned the former bite of his early work.

Florence is another in his recent line of more comforting star vehicles for Great Actresses surrounded in fussy manners or plum period finery (or both): Judi Dench in Mrs Henderson Presents and Philomena, Michelle Pfeiffer in Chéri and Helen Mirren in The Queen. The new film is a handsome production, too, and one that could easily be mistaken for a glossy “For Your Consideration…” ad in Variety.

Perhaps it doesn't add up to much but it's lovely to look at and touching. That the one joke conceit doesn't wear out its welcome is often thanks to Streep's pitch-perfect off-pitch singing. She somehow makes that funny every single time but we shouldn't be surprised that when the role calls for “blue” Meryl will bring “cerulean.”

And it's not just Meryl. The movie as a whole balances well on a very thin wire between its potentially mean-spirited premise and real affection for delusional dreamers. Nicholas Martin's screenplay and Stephen Frears direction actually go so far as to lionize delusions as life-saving coping mechanisms. Which… well, I'm not a psychotherapist so no judgments, but I am a movie fan and Florence Foster Jenkins is a good time.