A new study from the University of California has found that those most at risk of contracting HIV have the least access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

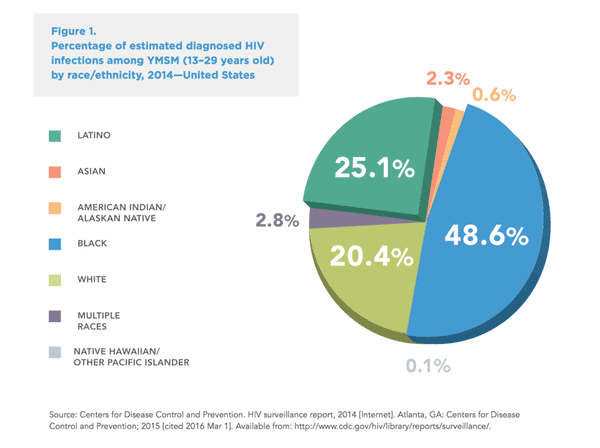

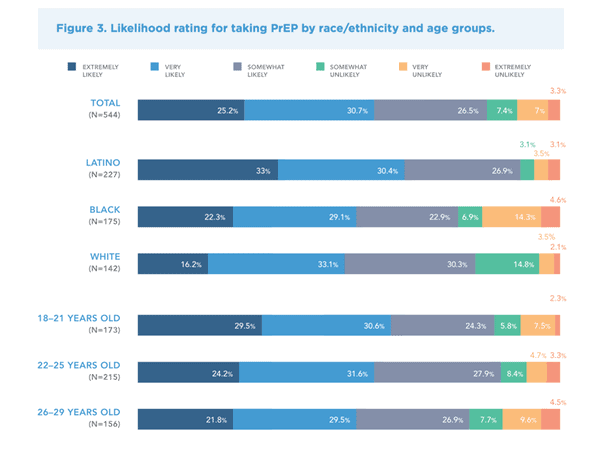

Populations that are most vulnerable to seroconversion are Latino and Black men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women, and those who live in southern states.

In a survey of gay and bisexual men in California, only a handful of participants reported having taken PrEP. PrEP use was highest among young white men, at 13.9 percent. For young Latino men, that figure was cut by more than half, while young black men represented less than 10 percent of people who started PrEP.

“This is not reflective of the HIV epidemic at all,” says Shannon Weber, founder of Please PrEP Me, an online directory of over 230 clinics in California that provide PrEP. “It is reflective about access, and where and how people are getting that information.” […]

“Black and Latino men who have sex with men, who are overrepresented in the epidemic, have low threshold access to the services,” says Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, assistant health commissioner overseeing the Bureau of HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

It's a broad racial disparity first reported in June by Gilead Sciences, the biopharmaceutical company that makes Truvada. White gay and bisexual men made up the biggest gains in PrEP usage in 2015, although they're far less likely to contract HIV in their lifetime. PrEP use among black men, on the other hand, has dipped since 2012. So while prescriptions for Truvada continue to rise significantly, McCord says, “What we're not seeing is perhaps where PrEP is needed and that is in higher risk communities.”

Interestingly, Republican opposition to Obamacare plays a factor in the limited availability of PrEP in the American south:

Those Southern cities most susceptible to an HIV outbreak – El Paso, Atlanta, Jackson, to name a few – are also in states that haven't expanded Medicaid, which does cover the costs of Truvada after a small co-pay. That means the preventive drug, which can cost upward of $1,564 for a month's supply, has become financially out-of-reach for hundreds of thousands of eligible PrEP users because GOP lawmakers refused to make healthcare accessible to people living in poverty. “Low cost services for HIV-negative people [are] practically nonexistent,” says David Evans, director of Research Advocacy at Project Inform.

Some major population centers have, however, begun expanding access to PrEP for at-risk communities:

Last year, San Francisco and Los Angeles ramped up efforts to increase PrEP use among men who sleep with men and transgender women after receiving grants from the CDC as part of the agency's Project PrIDE initiative. In June of this year, MAC AIDS Fund announced a two-year, $1 million citywide program in Washington, D.C. to educate and promote PrEP use among black women — one of the groups most at risk in a city that once had the worst HIV rates in the country. Last week, researchers from the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta launched a searchable nationwide PrEP provider database. And in the coming months, about 70 community-based clinics in underserved areas throughout New York City will start providing PrEP with the support of the city's Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

“People who don't have a voice aren't going to be walking into a clinic with a giant rainbow flag on it,” like the ones in Chelsea, the West Village and other LGBTQ-friendly neighborhoods, says Daskalakis. “We're creating the infrastructure in places that may not have that giant rainbow flag, and we're really proud of that.”