In 1983's East Village, a punk-looking, half-shaved RuPaul in over-sized rubber boots over leopard-print tights is dancing like a maniac on a poorly lit stage. She asks the audience at The Pyramid Club on Avenue A: “Do you hear me, New York? I wanna break out tonight. I will break out tonight.”

It's been more than thirty years, and we all know RuPaul's prophetic words rang true. The essence of queer underground culture, the subversive art of drag, was just moments away to take over the world—and she knew it.

Luckily, that seminal moment in LGBT culture was captured on film, and you can now see it at the Museum of the City of New York, as part of its brilliant new exhibition “Gay Gotham: Art and Underground Culture in New York,” a show about queer life, culture and art in New York City from early-20th century through the 1990s.

Curated by MCNY curator of architecture and design Donald Albrecht with historian Stephen Vider, MCNY Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow, “Gay Gotham” is a fascinating look at the impact and contribution of LGBT artists to New York's cultural life, and by extension, to the entire country's cultural and social life.

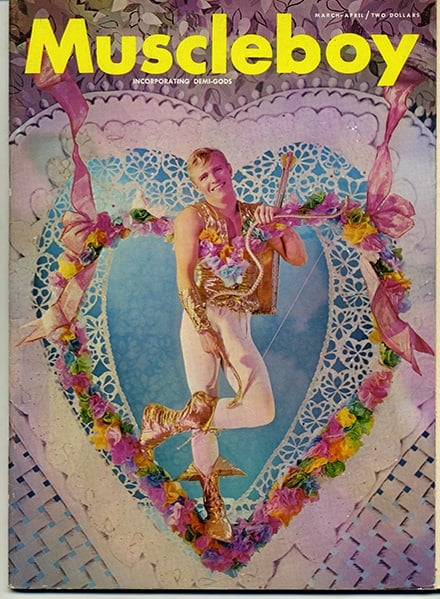

Albrecht and Vider show the story through the eyes of ten artists and their networks of friends and collaborators, from the 1910s until the mid 1990s. Some artists are household names (Leonard Bernstein, Andy Warhol, Robert Mapplethorpe), and others will come as new discoveries for many. Their work is presented in chronological order, along with memorabilia, ephemera, books and magazines, to provide social, cultural and political context.

The 225-piece show is the first of its kind in a major New York City institution, and it spreads across two galleries, on the second and third floor of the museum. (Hopefully, the MCNY has started a trend: U.K.'s Tate Britain has recently announced its first major “Queer British Art” exhibition in 2017.)

“Gay Gotham” is divided into three major chronological sections: “Visible Subcultures” covers the early 1910s to the 1930s, and it takes a look at how gay life flourished in neighborhoods like Harlem and Greenwich Village. “It should be very surprising for a lot of people to see how visible and widely discussed these neighborhoods, clubs, bars, and performers were,” according to Vider. The first gallery opens with artist and writer Richard Bruce Nugent, the most openly gay figure of the Harlem Renaissance. His work in the early 1920s unapologetically explored race, gender and same-sex desire. Next to Nugent, the work of “lesbian chic” poet and playwright Mercedes de Acosta is on display. She loved to dress in “mannish” clothes, and became famous for her affairs with Hollywood legends such as Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. Check out filmstrips of Dietrich from the 1930s from de Acosta's personal archives.

“Open Secrets,” still on the first gallery, covers the 1930s to the mid-1960s and shows queer culture under attack, in the years following the Great Depression.

Leonard Bernstein, the most prominent artist here, exemplifies the challenges gay artists faced in post-World War II America: a devoted husband to Chilean actress Felicia Cohn Montealegre and father of three children, Bernstein never came out publicly with fear of damaging his career.

On the bright side, visitors can see a scene breakdown of “West Side Story” with annotations by Bernstein and Jerome Robbins next to its inspiration: Bernstein's own annotated copy of Shakespeare's “Romeo and Juliet.”

On the opposite wall, an incredible series of polaroid-sized photographs taken by an anonymous photographer on the streets of New York City in the '60s: boyfriends hugging, a stylish gay cowboy, some old-fashioned cruising on 5th Avenue, and a man in tight jeans and proud of his erection indicate the closet bubble is about to burst.

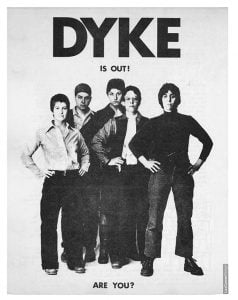

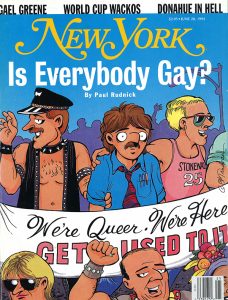

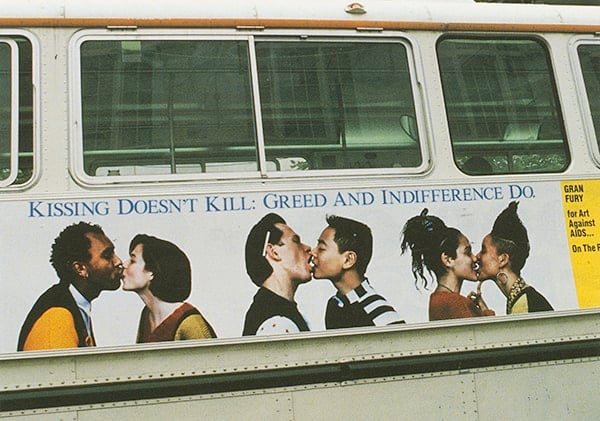

Upstairs, “Out New York” covers the years leading up to Stonewall until the mid-1990s, an era when anti-homophobia activism grew stronger; responses in the fight against AIDS changed art forever; and the “we're here, we're queer, get used to it” mentality was born.

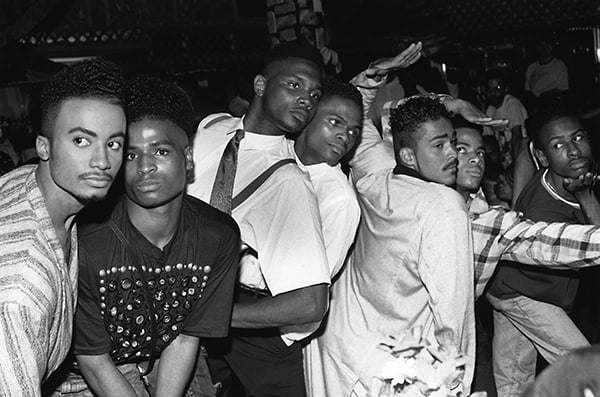

The entrance to the gallery alone might take your breath away. An illuminated floor-to-ceiling panel featuring two legendary children from the House of St. Laurent—Temperance and Octavia St. Laurent— welcome you to a new phase in queer life. (Octavia, who later in life started using her full name – Heavenly Angel Octavia St. Laurent Manolo Blahnik—was one of the performers featured in 1990's Paris is Burning, where her description of the different phases of model Paulina Porzikova granted her immortal status.)

“Out New York” opens with Andy Warhol, who functions like a bridge between the repression of the 1950s and '60s and the sexually explicit 1970s and '80s. A photograph of Warhol and Candy Darling taken by Cecil Beaton in 1969, and his silent film “Kiss,” shot at The Factory in 1963, is as close as one can get to sixties fabulousness.

The next wall is dedicated to Robert Mapplethorpe. An invitation to his first solo show and a series of photographs (of him, by him, of his jewelry, of his lover Sam Wagstaff) explores his sexually charged aesthetic, and hints at how he managed to transform his work from underground into high art.

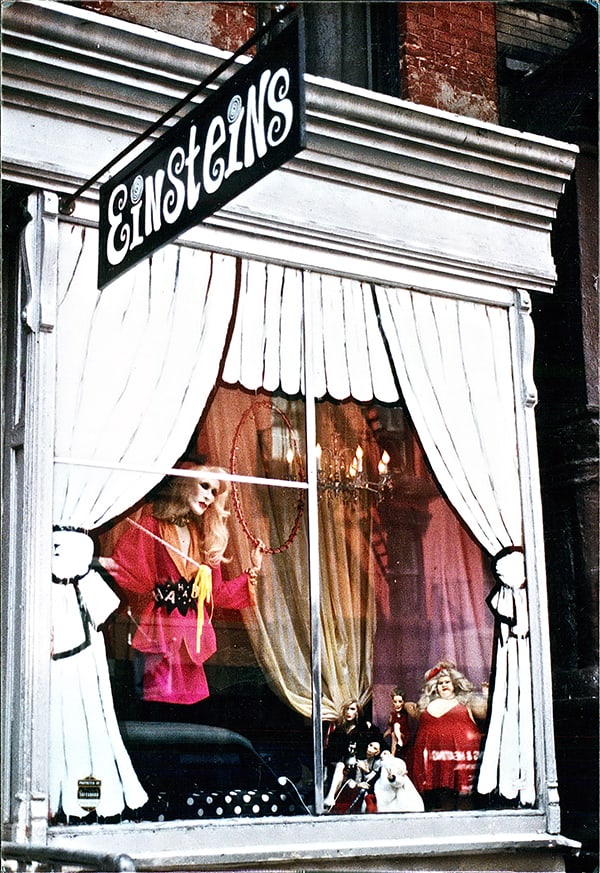

Feminist lesbian icon Harmony Hammond and choreographer Bill T. Jones are also featured in this gallery (choreographer Arnie Zane's video of Keith Haring painting the body of Bill T. Jones—Zane's partner— is a must-see); and a life-size doll of Diana Vreeland might turn transgender artist Greer Lankton, a well-known figure in the East Village art scene of the 1980s, into your new favorite artist.

In both galleries, video compilations highlight the importance of the “performing” elements of queer culture in New York: one of them shows the “Pansy Craze” of the bohemian 1920s and its many flamboyant performers, such as Jean Malin, Bert Savoy and Jay Brennan. It also shows a clip from 1932's “Call Her Savage,” the first film to depict a gay bar, illustrating the influence of New York's cultural queer scene in Hollywood.

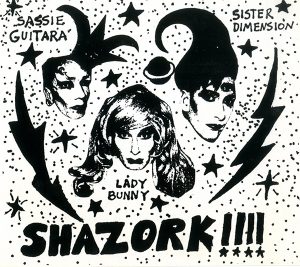

Upstairs, the compilation shows the serious (Tony Kushner's “Angels in America,”) the groundbreaking (Frank Simon's 1968 documentary “The Queen”) and the surreal (an angelical Lady Bunny singing “I'm dreaming when you look into my eyes” at The Pyramid in 1984.)

The elegant design by architect Joel Sanders adds a great deal of texture to the exhibition's narrative: most of the artwork hangs around the perimeter circle of the galleries, while maps that “charter an evolving gay geography in of New York” are featured in the center.

The walls are painted in lavender: dark and deep for the gallery covering the years before Stonewall, and lighter for the years after, when gay life became more visible. On the floor, lines connecting artist to their friends and collaborators give you a clear idea of the importance and magnitude of the networks.

That idea of network is, in fact, the theme that permeates the entire show: “how the marginalization and possible sense of separateness fostered a sense of community and collaboration,” according to curator Donald Albrecht. “You see it in every aspect of the show: people are photographing their group, collecting mementos of their group, are gathering in places, doing invitations to their events, they are taping each other, they are photographing each other, drawing each other.”

The networks even transcend generations. Warhol, for example, who came on the scene in the ‘50s, is connected to Mercedes de Acosta, who'd published her first book over three decades earlier. They became acquainted, she introduced his talents to her friends, and he even designed a cover for her 1960 autobiography.

Warhol was also friends with Charles Henri Ford, who co-wrote the gay literary classic “Young and Evil” with Parker Tyler in 1933 (on display at the exhibition), and whose network of friends included Carl Van Vecthen, George Platt Lynes and Cecil Beaton.

Looking forward, Warhol was a major inspiration for the early career of Robert Mapplethorpe, starting in the 1970s. Warhol's own Interview Magazine hired him as a staff photographer in the late 1960s, and some of the models for Mapplethorpe's jewelry line were part of Warhol's Factory circle.

A few years later, Mapplethorpe and Sam Wagstaff came across a never-before-published collection of male nudes by George Platt Lynes (also in the show). Those images became a huge influence in Mapplethorpe's photography.

A stunning 304-page book, Gay Gotham: Art and Underground Culture in New York, published by Skyra Rizoli and written by Donald Albrecht with Stephen Vider, accompanies the exhibition. Slightly different in structure (the book features seven of the ten portraits from the show, and it includes nearly 400 images), both the show and the book celebrate “the power of artistic collaboration to transcend oppression.” And give you chills, while doing it.

“Gay Gotham: Art and Underground Culture in New York,” runs through February 26, 2017 at the Museum of the City of New York.

Top image: Muscleboy March/April,1960s. James Bidgood, Courtesy ClampArt, New York City