Recently, Towleroad reported on queer activist Alexander Leon's viral tweets. This is Leon's original essay from which those tweets were adapted.

I still remember the first time I watched the Truman Show.

Strangely, I was immersed in water, my tiny bum poked down through a garish inflatable donut, staring at a screen which to my younger self seemed as big as the world. It was during a period of my childhood where my family were wont to go on punishingly long road-trips around the country, frequenting cramped caravan parks and sleepy roadside motels in the kind of frenetic appreciation for rural Australia reserved for first generation immigrants. We'd stopped by a waterslide-themed park for the day, my parents stoically submitting themselves to the torture of taking young children around a theme park in a show of good parenting. As the sunshine waned, we'd cosied up by a large wave pool set before an enormous screen, preparing for the park's movie night, which had been touted as a must-do. Families gathered like floating flocks in the water, paddling into prime positions and waiting for the film to commence. And as the screen flickered on, the opening titles falling on me like a filmic sermon, tiny Alex had his mind blown for the first time.

The Truman Show, for the uninitiated, tells the story of its titular character, Truman Burbank, who without his knowledge is the main character in an elaborate TV show, where hidden cameras capture his every move. Everyone he holds dear is a paid actor, the events in his life a carefully produced storyline. The film tells the story of his crushing realisation that the world he cherishes is a curated collection of falsehoods, that he has been conned all along. It was a groundbreaking film. Jim Carrey is phenomenal.

For younger me, watching up from my watery seat, the film was a revelation. It spoke to a sensation I had deeply felt since the moment I could speak and think for myself — the feeling that I was just like Truman, an unwitting character in an elaborate production. It was a feeling that had been circulating my subconscious for years, desperate to be articulated or validated. I was utterly convinced my life wasn't real. The entire thing was a set-up. I had been born into the world's largest theatre.

I had no proof, of course. Indeed, when I went searching for it I often found evidence suggesting the contrary, like the time I demanded my mum show me photos of my actual birth to prove she was my mother, convinced she'd come up short, only for her to provide just the thing in the form of a ghastly photo of barely-born me covered in gunk on her bosom. I quietly conceded that the evidence was irrefutable and attempted to move on. But entranced by my own personal conspiracy, I revisited the idea often, trying to hoodwink my parents with oddly specific queries on my origins which they'd diligently answer, bemused.

As a child, I became obsessed with the idea that my life was an elaborate production. It took me years to understand that the only one performing was me.

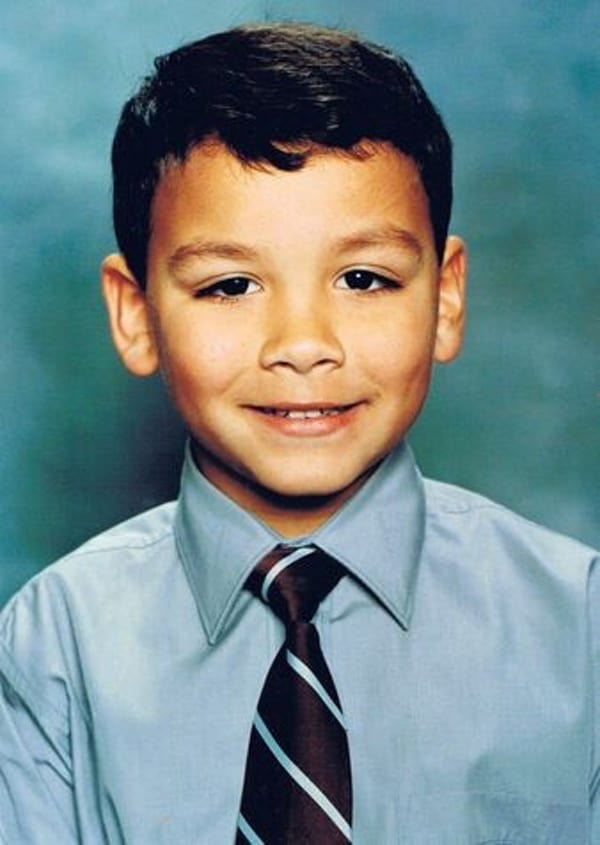

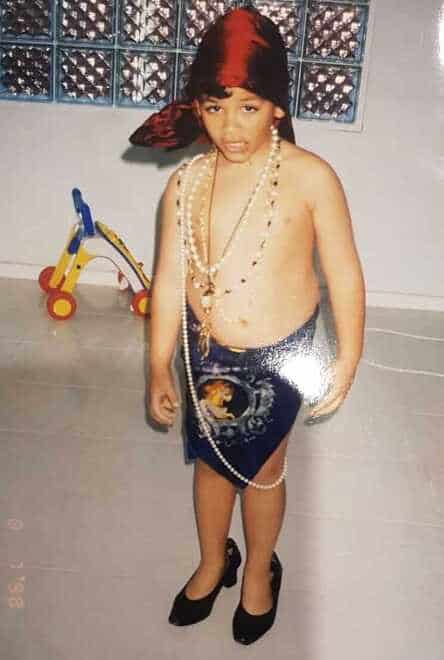

After a while, the conspiracy became more comforting than practical, like an old worn shirt I'd slip into when I felt too naked — grounding myself in something which I knew to not be true, but felt true. The actual truth, concealed in obscurity, was that encased in the quaint desire for my life to be a production was something sharper I didn't yet have the willingness or emotional acuity to confront. I had cast myself in a role because I had learned that my survival as a young, effeminate, brown boy, relied on play-acting. The simple act of being myself, to me seemingly banal, was often perplexing to those around me. Sometimes I'd say or do something, pick up a Barbie, try on girls clothes, make a passing but unmistakably girly gesture, that would incite distress or even anger from the adults around me. So, in fear of their scrutiny, I made the world a theatre, and myself its stoic performer-in-residence. After all, if it was all pretend, I couldn't get hurt.

As I grew older my acting prowess became too big a part of me to ignore. Capitalising on my insatiable desire to perform, my parents dutifully shuttled me from choir rehearsal to film audition, gawking at my ability to so uncannily inhabit the lives and personas of other people. And I loved it. As a teen I would delight my family, and later my few friends, by doing zany impressions of pop culture figures or running through a rolodex of regional accents like a lyrebird prodigy. The times in which I pretended to be someone else became precious to me, experiences of cathartic respite, where I'd imbibe wave after wave of intoxicating validation from the people around me, signalling that through the lens of my performance, I had worth.

So, I became prolific. Too prolific. And eventually, the curtains never came down. I had learnt, in my ungainly ascension into adolescence, that my true self, the person behind the performance, couldn't possibly fit in. Whether it was teachers openly chastising me for my femininity, or the violent reprimand from boys in my year as they laughed the word faggot into my ear before I knew what it meant, I had come to internalise the idea that my authentic self was fundamentally and irreparably flawed. To act out a different life was to escape this predicament, so I sacrificed authenticity to minimise humiliation and prejudice. I built up an enviable, hardy suit of armour.

And then, years later, when I finally came out of the closet, desperate to share that I'd been unwittingly acting the entire time, I got stuck in it.

Coming out of the closet is considered a monumental step in the life of a queer person. It's lauded as a pivotal juncture where you throw off the shackles of your deceit and step into your true self. But in reality, coming out of the closet is just the first clumsy leap in a formidable, punishing obstacle course. For me, coming out felt like finally admitting that I had lived my entire life pretending to be someone else as a mechanism to survive, and now suddenly confronted with the opportunity to be my actual self, I had my first ever experience of stage fright, the irony ringing mirthlessly in my ears.

In truth, I didn't know who my actual self was. And how could I? The barely out version of me was a collection of fragments, pieces of me which I'd left to atrophy rammed up against pieces I'd contorted into unsightly shapes to protect myself. I'd closed the door of the closet only to be confronted with another door, this time with an elaborate lock, emblazoned “finding yourself”.

This task, of finding ourselves, is a massive, existential and deeply difficult exercise that all queer people share but seldom collectively acknowledge. It's a task that leads many of us down treacherous paths, chasing other forms of escapism that mirror the closet, drinking or drugging ourselves into other forms of suspended reality where we can pretend again. It's a task that involves enormous emotional and spiritual upheaval, which many of us are forced to do alone, with scant resources, or little in the form of mentorship. It's a task that takes time, that demands we be patient and compassionate with ourselves, that presents countless obstacles and potholes. Sometimes the task feels like a burden, the weight of which breeds resentment. Other times it's a joy, as we untwist ourselves from the contortions we'd previously held and relax into who we are.

This task, of finding ourselves, is a massive, existential and deeply difficult exercise that all queer people share but seldom collectively acknowledge. It's a task that leads many of us down treacherous paths, chasing other forms of escapism that mirror the closet, drinking or drugging ourselves into other forms of suspended reality where we can pretend again.

Additionally, and frustratingly, it's a task often not recognised or validated by others in our life. Our family, our friends, are often not aware that life after the closet isn't the simple relinquishing of our previous self and the effortless taking up of a new-and-improved queer persona, but rather a complex and arduous process of unlearning the often toxic ways in which we have dealt with negative feelings about ourselves and our place in the world. They see the closet door wide open and don't understand how we could still be hurting. Our struggle becomes invisible.

But through this struggle I have stumbled upon an extraordinary truth. The biggest revelation of my life has been realising that in this tremendous labour lies an immense privilege. As I've grappled with who I am, sometimes to the point of feeling like I might break, I have realised that the opportunity to do so outside of societal expectation and influence is not one that is afforded to everyone, with many straight, cisgender people never explicitly delving into this cataclysmic internal confrontation. Through therapy and the support to try out different versions of myself until I found the one who felt the truest, I have become a person that I am proud of, who doesn't shy away from the aspects of himself he was historically desperate to conceal. Of course, I'm still on my journey, and I still have my wobbles — unlearning is a process. But my journey to rediscovering who I am has made me reborn. It's been my second chance at life.

In the dramatic final scenes of the Truman Show, Christof, the director of the show that has made up Truman's entire life, explains Truman's predicament to the viewers. “We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented”, he says coolly, to an increasingly frantic Truman.

When I look at our world now, a world in which queer people's association with the culturally and socially taboo is diminishing, our legal freedoms are being secured across the world, members of our community are permanent fixtures in popular culture, and we are finding success in all walks of life not in spite of but in harmony with our sexual orientation or gender identity, I see a reality that a younger me just might have dared to accept, and perhaps even have chosen to be a part of. A new reality we are all continuously creating.

It's undeniable that there is still a monumental amount of work to be done for our community. But in my moments of defeat, where the task of figuring out who I am feels all too burdensome and the world feels acutely unfair, I'm reminded of the fact that my struggle, as exhausting as it may be, is a gift through time to the generations of queer people yet to come. My authenticity, our authenticity, allows us to create a reality in which young queer people will see an opportunity to thrive not as an actor forced to play a part, but simply as themselves, side-stepping the trauma of the closet and living their truth from day one. We struggle so that they don't have to.

And I can't think of a gift I'd rather give.

Alexander Leon is a writer, campaigner and human rights activist centering on LGBT+ rights, anti-racism and intersectionality in social movements. You can find him on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.