There's a sustained quality of attention intrinsic to live theatre. Generally, it's cultivated through focusing on actors in a shared space (and please, yes, by all means put down your phone). Belgian director Ivo van Hove has conceived his new production of West Side Story, opening at the Broadway Theatre tonight, for a generation he assumes requires the sort of ceaseless, fractured stimulation we receive from other media in order to engage with a story happening right in front of us. Its dizzying cornucopia of live projections, pre-recorded footage, and slick contemporary aesthetics seem designed to make the story feel closer to the here and now. But they rather serve to keep audiences at a cold, clinical remove from the love that hurtles toward tragic ends.

Van Hove's update to the 1957 classic, conceived by Jerome Robbins with a script by Arthur Laurents, score by Leonard Bernstein, and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, includes substantial cuts (the show runs an hour forty-five minutes with no intermission) and a modern reimagining of its racial dynamics. Here the Jets are a mixed gang of Black and white (mostly) men who consider the Puerto Rican Sharks unwelcome foreigners. It's not entirely easy to square why racial tensions cut one way and not another. But the multiracial casting does highlight how arbitrary animus can be (who even knows why the Capulets and Monagues couldn't get along?), and offers an opportunity for timely nods to police brutality against Black men, in a sobering reimagining of “Gee, Officer Krupke.”

Video design by Luke Halls, as especially evidenced by that last number, is not exactly subtle. Costume design by An D'Huys and lighting by Jan Versweyveld (Van Hove's creative partner) fall back on obvious color contrasts to differentiate gangs not strictly separated along racial lines.

Out of this urban conflict, styled much like a fashion ad for G-Star RAW, comes the meeting of two star-crossed teens. Here's where Van Hove's production starts to betray a greater interest in visual display over settling on a cohesive and impactful mode of storytelling. We meet Tony (a superb Isaac Powell) and Maria (Shereen Pimentel) in Doc's drugstore and what the playbill lists as a sweatshop, respectively. Both interiors are hyper-realistic, set too far upstage to see clearly first-hand; and so we encounter them in blown-up live-feed, as if watching a multi-cam soap. Acting for the camera generally assumes a subtlety that's not modulated here, so the effect feels like a jarring slip into an actual teenage soap.

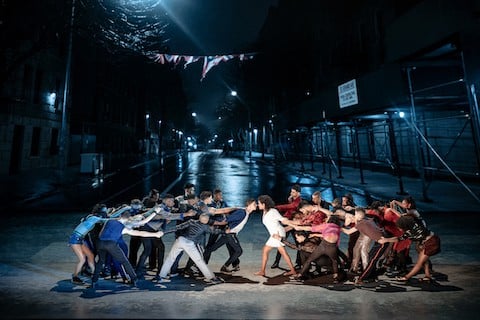

In a way, that treacly quality is more attuned to the story's inherent melodrama than the production's gestures toward heightened realism. Falling in love and dying for it within 36 hours (as the playbill timeline makes clear) is pretty far from plausible reality, maybe especially for the generation presumed to be pictured here. But Van Hove doesn't deploy his many lenses to deliver tearful closeups or cultivate any sense of intimacy between the lovers. Rather, the live-feed panning around group numbers tends to distract from choreography by Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, while stock clips that directly reference social ills feel overdetermined (you'll not be surprised to see the border wall.)

If there's a breakout star here, it's Powell, previously seen on Broadway in Once on This Island. The production's best moments feature Powell's Tony on a bare stage, delivering honey-dipped takes on “Something's Coming” and “Maria.” Van Hove has excised “I Feel Pretty,” leaving Maria without a solo, which is a shame; Pimentel's operatic soprano, though somewhat out of sync with the company, might have added lovely texture to the song. As it is, Pimentel has precious little character development, and the heat between the lovers suffers for it. It does, in fact, help when the women on stage are afforded as much interiority as their partners.

If there's one thing Van Hove might have learned from the devoted yet doomed lovers, it's some measure of trust. He might have trusted the tune of a timeless story to resonate loud and clear, without drowning it in visual effects that feel closer to gimmick than a clear point of view. Or trusted his actors to perform their roles free from artificial mediation. And perhaps most of all, he might have trusted audiences to pay attention without fighting to figure out where it ought to go. It's why we come to the theatre in the first place.

Note: A growing movement, including on-site protests and a petition with nearly 50,000 signatures, has been calling for the removal of Amar Ramasar from the role of Bernardo. Ramasar was dismissed and then rehired as a principal dancer with New York City Ballet after sending and receiving explicit photos of fellow company members without their consent. Read more about the movement, and the women on either side of it, here and here.

Recent theatre features…

Towleroad's Top 10 Plays and Musicals of 2019

‘Jagged Little Pill' Is a Raw and Explosive Portrait of Suburbia on the Brink: REVIEW

On Broadway, ‘The Inheritance' Sprawls but Rarely Cracks the Surface: REVIEW

Broadway's ‘Moulin Rouge!' Is a Dystopian Glitter Bomb of Empty Excess: REVIEW

Follow Naveen Kumar on Twitter: @Mr_NaveenKumar