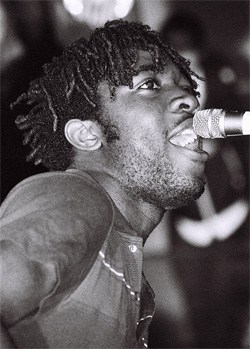

In a revealing interview with Bloc Party frontman Kele Okereke, the Guardian notes that two tracks on the band's upcoming release, A Weekend in the City, seem to explore an interest in gay issues (“Two songs, ‘I Still Remember' and ‘Kreuzberg', seem to explicitly explore homosexuality. The former is about a crush between two schoolboys (‘We left our trousers by the canal') The latter is about gay promiscuity.”) and takes the opportunity to ask the vocalist, who also plays guitar for the band, whether this is a sign of the singer being open to talking about his sexuality, which up till now has been something he has avoided:

“During the many interviews Bloc Party conducted during 2005, as their debut album Silent Alarm went from critical rave to million-selling commercial hit, from Mercury nominee to NME's Album of the Year, the subject of whether Okereke is or isn't gay was the pink elephant in the room. In a musical form that is usually beerily, boorishly white, male and heterosexual, Okereke was a refreshingly different kind of indie icon. The possibility that he was not just unusual but unique – a black, gay role model for indie kids – meant that for many fans the focus seemed necessary rather than just prurient. Nonetheless, just as he hated being reduced to ‘black guy in indie band', he refused to be drawn either way on his sexuality.”

Okereke says: “I think I'm going to have to [talk about it]. With the first album I didn't think it was essential to the experience. I didn't want to have to talk about it in a tabloid way. It wasn't there in the songs, so why did people need to know? But yeah, there are songs on this record that do feel like they're about desire, longing. So yeah, I am gonna talk about that.”

One of the gay-themed songs on the album, “For England”, is an exploration of bullying which also touches on the death of gay barman David Morley and the sick phenomenon of “Happy Slapping” in which violent acts are captured on camera for sport. Morley's killers fatally beat him and captured it all on their cell phones. Said Okereke: “The whole idea of happy slapping … Filming you causing pain to someone, for your own amusement – that really repulsed me. That song is about the fear I have about what could happen on a night out. I have the feeling that it's only a matter of time.”

One of the gay-themed songs on the album, “For England”, is an exploration of bullying which also touches on the death of gay barman David Morley and the sick phenomenon of “Happy Slapping” in which violent acts are captured on camera for sport. Morley's killers fatally beat him and captured it all on their cell phones. Said Okereke: “The whole idea of happy slapping … Filming you causing pain to someone, for your own amusement – that really repulsed me. That song is about the fear I have about what could happen on a night out. I have the feeling that it's only a matter of time.”

Another track, “I Still Remember”, deals with an unspoken sexual desire between men — heterosexual men. Norman B., of SlowCode, who tipped us off on Okereke's coming out, offers it up on his site:

Okereke explains “I Still Remember”: “I can't tell you how many times I've been propositioned by straight boys…Yeah, yeah. It happened a lot before all this [the band] started happening. This is probably a contentious issue, but I swear that I could always see it in people, in the way that guys would need to be touching other guys. You could see there was something they couldn't say aloud. And I saw it when I was at school. And I guess ‘I Still Remember' is an attempt at trying to confront that. I don't think that my sexual impulse is that bizarre or foreign. [But] the way that it's supposedly discussed in mainstream culture is [that] it's a crazy thing. But I know from my own experiences a lot of heterosexual boys had feelings or experiences when they were younger. And that's not really ever spoken about, that un-spoken desire. Not two gay boys, but the idea of two straight boys having an attraction, or there being an attraction that's unspeakable – that was the idea of that song. When was the last time you heard an interesting pop song that actually tried to give you a different perspective on desire? I didn't talk about it when I did interviews for the last record because it wasn't an area really reflected in the music; I didn't talk about race for the same reason. Why was that still a discussion point? The only reason it was a discussion point was because of the racial prejudice that exists in the mainstream media.”

Okereke explains “I Still Remember”: “I can't tell you how many times I've been propositioned by straight boys…Yeah, yeah. It happened a lot before all this [the band] started happening. This is probably a contentious issue, but I swear that I could always see it in people, in the way that guys would need to be touching other guys. You could see there was something they couldn't say aloud. And I saw it when I was at school. And I guess ‘I Still Remember' is an attempt at trying to confront that. I don't think that my sexual impulse is that bizarre or foreign. [But] the way that it's supposedly discussed in mainstream culture is [that] it's a crazy thing. But I know from my own experiences a lot of heterosexual boys had feelings or experiences when they were younger. And that's not really ever spoken about, that un-spoken desire. Not two gay boys, but the idea of two straight boys having an attraction, or there being an attraction that's unspeakable – that was the idea of that song. When was the last time you heard an interesting pop song that actually tried to give you a different perspective on desire? I didn't talk about it when I did interviews for the last record because it wasn't an area really reflected in the music; I didn't talk about race for the same reason. Why was that still a discussion point? The only reason it was a discussion point was because of the racial prejudice that exists in the mainstream media.”

Okereke's cautious coming out is colored by the “definite homophobic bias-slash-persecution” he sees from the music press regarding out gay people. Said Okereke: “It's not something that I'd be inclined to talk about … It isn't black and white. It isn't clear-cut. Britain has always had a love/hate relationship with gay public figures. They're treated as funny and inoffensive and camp. But then when a seemingly heterosexual person seems to display an inclination for the other team it becomes this real hounding situation. You're allowed to exist if they're [sic] seen as a kind of sub-class. Something ineffectual, a comedy Kenneth Williams character.”

But he tells The Guardian the difference he could make to a young kid (as an indie rock icon of Nigerian heritage) just might trump those worries:

“I guess that's the only reason [to speak out], isn't it? To speak to young people in their impressionable formative years – and say something that could help them make sense of their lives. Lessen the sense of alienation and isolation that they might have. I think that's something that definitely … I'd be proud of. That we could say that there are alternative ways of behaving, of living one's life.”

A Little Britain [slowcode]

21st Century boy [the guardian]