Editor's note: Seven candidates met on the debate stage in New Hampshire on Feb. 7, sparring over questions on health care, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, race and more. We asked three scholars to pick out some of the night's biggest moments as New Hampshire prepares to vote on Feb. 11.

Marie Eisenstein, Indiana University Northwest

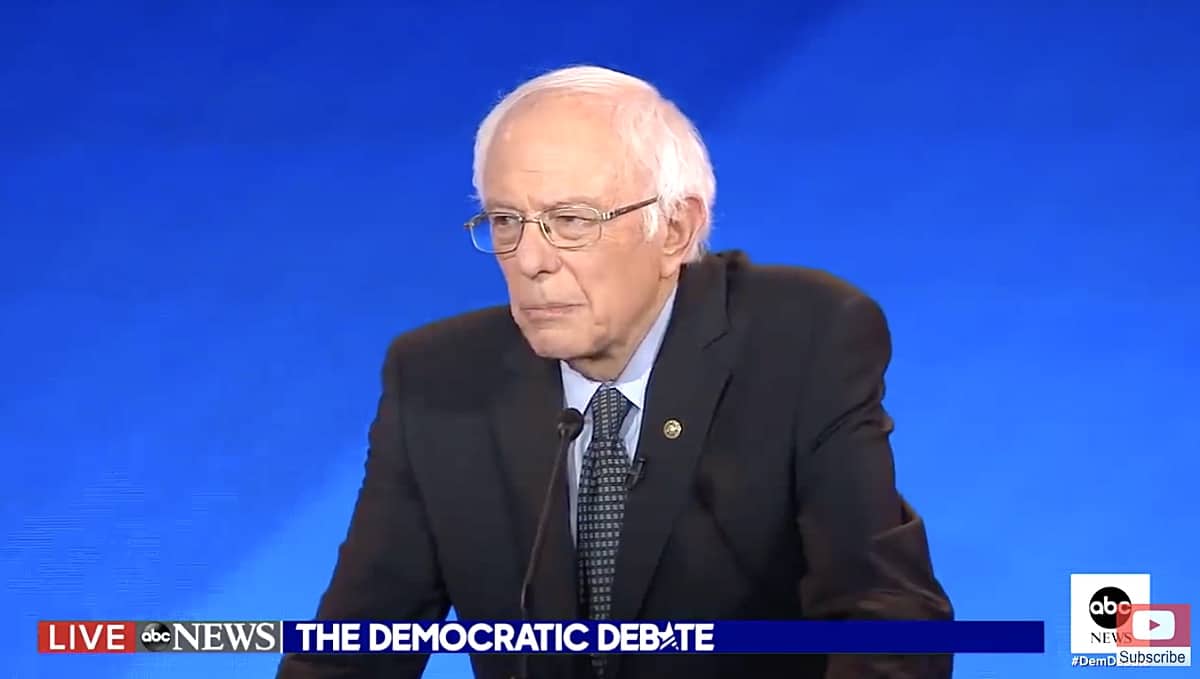

“Is anyone else on stage concerned about having a Democratic Socialist on the top of the Democratic ticket?” – George Stephanopoulos

Gallup polls show that more Americans consider socialism “a good thing” today than in the 1940s – 43% agreed with that statement in 2019 versus 25% in 1942. However, those same polls show that 51% of Americans see socialism as “a bad thing” in 2019, a number that was only 40% in 1942.

The real question is: Will Americans be less likely to vote for someone who is a socialist or a democratic socialist? On that question, Gallup polls from both 2015 and 2019 suggests that 47% of Americans are willing to vote for a socialist.

That means more than 50% of Americans are not willing to do so. This is a serious issue for the Democratic Party in trying to unseat President Donald Trump, who regularly denounces socialism. These data certainly suggest this is a thorny issue for the Democrats if Bernie Sanders secures the Democratic nomination.

Just how thorny an issue establishment Democrats consider this was vividly on display recently. Hillary Clinton decried Sanders' ability to unify the Democratic party and expressed concern that Sanders “promise[s] the moon”“ but will be unable to “deliver” it.

Political commentator James Carville lamented, “Do we want to be an ideological cult, or do we want to have a majoritarian instinct to be a majority party?” At the heart of both Clinton's and Carville's critique is a concern over whether a socialist can win for the Democrats.

This issue – who can beat Trump in November – was a central theme of tonight's debate. While candidates such as Buttigieg, Steyer, Biden and Klobuchar did not come out and say a socialist cannot win, they certainly tried to highlight what they believe is their more centrist appeal.

Aaron Kall, University of Michigan

“We're gonna have to take Mr. Trump down on the economy, because if you listen to him, he's crowing about it every single day and he's gonna beat us unless we can take him down on the economy, stupid.” – Tom Steyer

“It's the economy, stupid” is a famous political phrase coined by Democratic strategist James Carville in 1992 during Bill Clinton's presidential campaign. Carville has been prominently featured in the news recently for accusing Democrats of “losing their damn minds.”

As Carville, Steyer and other political prognosticators have indicated, the state of the U.S. economy between now and Election Day may be the most important factor in the 2020 presidential election and single-handedly determine whether Trump wins reelection.

According to the latest Gallup News poll, Trump's job approval rating has recently risen to 49% following his impeachment acquittal vote. That's the highest number he's experienced in this poll since becoming president. The same poll found that 63% of Americans approve of Trump's handling of the economy, which is the highest such rating found by Gallup News since President George W. Bush in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

On Feb. 7, the Labor Department announced that employers added 225,000 jobs in January and the unemployment rate remains near a half-century ebb. Conversely, the U.S. economy created over 500,000 fewer jobs between April 2018 and March 2019 than had previously been believed.

In one regard, it's shocking that a president that enjoys such tremendous economic support continues to have a job approval rating below 50%. Possible explanations for this dichotomy include a rising fiscal deficit and voters' failure to credit Trump for the country's economic success, given his policies or other perceived shortcomings.

Despite this disconnect, the economic impact of the coronavirus and other unforeseen economic events between now and November could end up having a disproportionate impact on the 2020 presidential election. If so, Steyer's quote from the debate in New Hampshire will end up looking quite prescient.

Joseph Cabosky, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

“Young people came out in higher numbers than they did during Obama's historic 2008 campaign. And if that happens nationally, we're going win and defeat Trump.” – Bernie Sanders

Sanders is claiming that, despite the lower than expected turnout in Iowa this year, the 18- to 29-year-old turnout was higher than it was when Obama won the 2008 caucuses.

Is this argument true? Not really.

In this year's Democratic Iowa caucuses, 24% of voters were 29 or younger. Sanders is right in the sense that, in 2008, only 22% of voters in the Democratic Caucus were 29 or younger.

That said, there are two important notes. First, total turnout in the 2008 Iowa caucuses – about 240,000 – was much higher than turnout this year, just over 176,000. Thus, while younger voters were a greater percentage of the vote, the youth vote overall was down nearly 20%.

Second, Sanders is implying he brought out the youth vote this year. It is absolutely true he dominated with those under 29, pulling in 48% in entrance polls. But, in 2016, he obtained 84% of voters under 29 in Iowa entrance polls.

In 2016, only 16% of those under 29 went with someone other than Sanders. But this cycle, Buttigieg, Warren and Yang all received double-digit results with younger voters.

What does this mean for the general election? General election exit polls in Iowa showed young voters stayed relatively flat between 2008 and 2016.

The big difference? In 2008, Obama won 61% of young Iowa voters. Yet, in 2016, Trump beat Clinton among that same group with 48% to her 42%, a huge swing.

So, predicting a general election based on the youth vote in a primary, as Sanders is trying to do, can be highly problematic in swing states like Iowa.

[Insight, in your inbox each day. You can get it with The Conversation's email newsletter.]![]()

Joseph Cabosky, Assistant Professor of Public Relations, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Aaron Kall, Dean of Students, University of Michigan, and Marie A. Eisenstein, Associate Professor of Political Science, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.