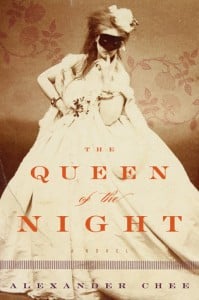

Alexander Chee's feverishly awaited, extravagantly entertaining second novel—his first since 2002's acclaimed ‘Edinburgh'—begins with a proposal. Lilliet Berne, the dazzling, 19th-century opera star who serves as Chee's narrator, is approached by a young man at a ball. He's a writer, he says, and he wants her to sing in an opera that's being made of his work.

As the writer continues, Lilliet's interest turns to concern and then to fear as she realizes the story he's telling is her own. She has kept her past closely hidden, and she takes the writer's proposal as proof she's been betrayed by one of the three intimates who know her secrets. Her search to find out which is the engine of Chee's novel, which uses visits to each of these three as a launching board to explore Lilliet's past.

As the writer continues, Lilliet's interest turns to concern and then to fear as she realizes the story he's telling is her own. She has kept her past closely hidden, and she takes the writer's proposal as proof she's been betrayed by one of the three intimates who know her secrets. Her search to find out which is the engine of Chee's novel, which uses visits to each of these three as a launching board to explore Lilliet's past.

It's a baroque story, ranging from the plains of Minnesota to the grand palaces of Europe, passing through circuses and brothels along the way. Orphaned by illness, forced to make her living by her wiles and by the great, miraculous gift of her voice—which she understands from early childhood to be a source of both power and danger—Lilliet sheds identities and lives multiple times. She lives as a prostitute, a maid, and a kept woman, before she becomes the diva who will make emperors bow to her.

Chee's novel isn't just about opera; it also takes on opera's aesthetic, embracing the surprises and sudden reversals, the extraordinary coincidences that can make operatic plots implausible and that also have something to do with how they access the sublime. The Queen of the Night is committed throughout to the operatic mode, inhabiting heights and depths of both social stratum and emotion. “My subject here is love,” Lilliet declares, and she means love governed by fate in a world where what seems to be an amorous rivalry can have world-historical consequences. Never does this book rest in that middle place which is the usual purview of the contemporary novel, what we sometimes call “everyday life.”

In this sense, like a few other recent books (Donna Tartt's The Goldfinch comes to mind), Chee's use of the novel is decidedly old-fashioned, hearkening back to a Dickensian conception of the standard of “realism.” But Chee is also asking questions about gender, identity, and power that are as urgent today as ever—and he is playing very sophisticated, very contemporary games with narrative and genre.

“The details of my roles had become the only details of my life,” Lilliet complains in the first pages of the book. This is true not just for roles she plays on stage, but also for the increasingly complicated roles she plays as she improvises her life after losing her entire family to illness. She takes these roles on as temporary expedients and finds that they become identities. Late in the book, she acknowledges that the great question of her life is not “Who am I?” but rather “What could I be?” Her brilliance as a performer comes from the fact that she is not in search of some essential, fixed personhood but of a series of roles she can fill.

It's exhilarating to watch a woman try to seize control of her life, insisting she is its master. But the governing spirit of this thrilling book is “the ridiculous and beloved thief that is opera”—and opera is almost always cruel to its heroines. Tragedy comes as Lilliet realizes she is in fact a pawn in a game played by others, who are in turn pawns in a larger game whose players Lilliet can't even discern. Chee's novel, from one vantage a sweeping, historical novel, is from another an intricate puzzle of inlaid stories.

It's exhilarating to watch a woman try to seize control of her life, insisting she is its master. But the governing spirit of this thrilling book is “the ridiculous and beloved thief that is opera”—and opera is almost always cruel to its heroines. Tragedy comes as Lilliet realizes she is in fact a pawn in a game played by others, who are in turn pawns in a larger game whose players Lilliet can't even discern. Chee's novel, from one vantage a sweeping, historical novel, is from another an intricate puzzle of inlaid stories.

“Whose story was I in?” Lilliet asks herself repeatedly, finally striking on the right question; and increasingly she feels herself trapped in a plot she's lost control of. She'll come to question everything she's trusted in her life, including, perhaps most of all, the voice that has made so much possible for her. The Queen of the Night is, finally, maybe most profoundly about the gamble of art, the risk of entrusting one's fate to an instrument that always threatens to fail. “You could devote yourself relentlessly to art and there would be no great reward,” she thinks late in the book, as she begins to comprehend the steep price art will exact from her. “You could go to your death for all of your talent thinking you had failed at your great work.”

Early in the book, Lilliet wonders, “Why was there never an opera that ended with a soprano who was free?” Alexander Chee's unforgettable and breathtakingly confident opera of a book might serve as an exception. But it also reminds us at how steep a price freedom comes.

Previous reviews…

A Year in Queer Reading

Lori Ostlund's ‘After the Parade'

Christopher Bollen's ‘Orient'

Michael Klein's ‘When I Was a Twin'

Connect with Garth Greenwell on Facebook and Twitter.